by Barbara Fischkin

Part One

This story begins, as no great story ever has, with a dustbuster.

That’s right: A cordless, rechargeable handheld vacuum cleaner. If you don’t know, consider yourself lucky. It means you have had so much household help, that you never needed to recognize that dustbusters exist. Align yourself with George H.W. Bush, amazed, as he was, by a supermarket scanner.

A dustbuster once infiltrated my life and as much as I would like to make it the culprit of part one of this story, I blame two other operatives. For a dustbuster to be an actual culprit it would have to star in an anime film—or take on the alternative meanings assigned to it by the Urban Dictionary. (Don’t go there for this particular word, unless you want to read about raunch—or worse—ice hockey.)

As for the actual culprits, they are my husband Jim Mulvaney and his late mother, Eileen O’Keefe Mulvaney. My husband is an intrinsically good guy. But nobody is perfect. My mother-in-law—whom I loved deeply—had her own flaws. Super practical, but more about other people’s needs as opposed to her own. When we cleaned out her house, we found scores of nearly identical striped, button-down oxford shirts in their original packaging. I realized it was the shirt she wore on a daily basis. She was not a serious hoarder. She just hated going to the dry cleaners.

My husband is also a romantic. During nearly forty years of marriage he has given me lots of jewelry, often antiques from the countries where we lived as young foreign correspondents. He did not steal any of these pieces, as far as I know. As a romantic, he is also entertaining, sometimes at a risk to both our psyches. Before our marriage, when we were reporters for the same newspaper, he relished ordering me huge bouquets of flowers to be delivered in our large, open newsroom.

He instructed the delivery boy to slowly saunter through a maze of reporters and editors, singing: “Flowers for Barbara Fischkin.”

The ink-stained wretches, male and female, sang back: “Is she really going out with him?”

The flower act was nice, if weird. It required my husband to pay attention. When he doesn’t, a dustbuster happens. In this case my mother-in-law, practical on my behalf, sealed the deal.

I should have predicted the gift debacle that occurred on May 8, 1988, eight months after our elder son was born. On that date, which will go down in family history—mine, anyway—my husband and his mother, their lapses working in cahoots, presented me with my first-ever Mother’s Day present.

Yes, a dustbuster.

I cried. Those were not tears of joy.

“Don’t you just love it?” my mother-in-law said, her famous blue eyes aglow.

Ah, no, I thought.

“Of course she loves it,” said my husband, his own famous blue eyes similarly aglow.

Some background:

It was a tough first pregnancy, although this had nothing to do with the baby inside me. He was just fine in that womb of mine. Others, though, were dying around us, specifically my mother and father. I loved my parents, if not their timing in this instance. Married for more than fifty years, they managed to expire from natural causes within three months of one another—during the fifth and ninth months of that pregnancy. In the midst of all of this life, death, pathos and shiva-sitting from near and afar, we made a long-planned move from Long Island to Mexico City so that my husband and I could report from a Latin America bursting with news.

After the birth, I reported my brains out, baby in tow. I loaded my son into a kiddie backpack, interviewed as he played with my hair and wrote stories from Mexico for the New Yorker and the New York Times. I took him on planes to report for Parade magazine from Guatemala and to meet up with my husband in Managua—Daniel Ortega patted little Danny on his blond head—and then Panama City, where martial law was declared as we landed.

Ultimately, the three of us flew back to Long Island for Mother’s Day.

I did not need a dustbuster. I needed a Spa Package.

Yes, I did try the dustbuster. It did not pick up big chunks of anything. It needed to be emptied a lot. Dust clung to its filter, with the same intensity as my infant clung to me. It smelled funny—and offered no help changing diapers. The only advantage it had over a vacuum was portability and size.

I imagined a scene—burgeoning anime, perhaps— in which a typical and unremarkable vacuum cleaner comes face-to-face with a dustbuster and laughs its own bulky hose attachment to smithereens. I can hear that vacuum now. “You little squirt, if there is a natural disaster such as a flood, a fire, an earthquake or even the rare tsunami, do you really think rescue vehicles will be loaded with the likes of you? No, siree. In a disaster you will shrink to nothing and we, vintage home appliances and enduring electrical Masters of the Universe, will save the day. “

Back in Mexico City, our numerous maids—as an American expat I was a temporary member of the privileged class—also laughed at the dustbuster. Then they returned to sweeping floors with their beloved straw brooms. Our house was always spotless.

Part Two

I had not thought about the dustbuster for ages, until Christmas 2023. The past years had been tough times for our family, for most families and for the world. We had spurts of joy but there was Covid-19 and then Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, the Israel-Hamas war and Trump reinvigorated. I was looking forward to a happy Christmas at home. Chanukah, earlier in the month, had been sweet. My husband bought me the dutch oven for which I had yearned. A tool, not an appliance—or a culprit. I had recently and uncharacteristically been cooking a lot.

Cooking is an issue with me.

Although my own mother was extremely nurturing, she could not cook. My grandmother, raised in an Eastern European shtetl, lived with our family in Brooklyn and ruled the stove. She had many traditional specialties, including chicken soups, kreplach, brisket, stuffed cabbages, latkes and honey cakes. What it seems she did not have was the patience to instruct my mother.

My grandmother died when I was two years old, another example of poor familial timing. After that my mother, left to her own devices in the kitchen, trended towards Eisenhower-era cuisine, albeit kosher. She ran her dinner schedule with military precision. Hamburgers, steak and lamb chops rotated on Mondays, Tuesdays and Wednesdays but no other days of the week. The meals were always balanced. Sometimes with baked potatoes, mashed potatoes or instant ones. Or Uncle Ben’s Minute Rice. Thanks to Sam, the local produce man, we had vegetables, primarily carrots and green beans, always overcooked. There was corn on the cob in season. Little pieces of corn were included in the mixed vegetables that sat in boxes inside our refrigerator’s small freezer. Thursdays meant fish sticks. Friday chicken (salted raw at home, as a second religious rite). My mother rounded out each week with leftover chicken on Saturday and on the seventh day fried salami and eggs. I thank Hostess and an occasional Sara Lee or Entenmanns for desserts.

Some Sundays my mother fell under the spell of Genesis and decreed a rest from the kitchen. We ate out at our local delicatessen where I ordered tongue on rye, never thinking about the origin of the tongue. Other Sundays we had takeout pizza or Chinese, served on paper plates, so our dishes remained kosher even if we did not. On special occasions, after Broadway shows in Manhattan, it was either Howard Johnson’s or Lou G. Siegels.

As a young woman, I vowed to be a better cook than my mother. I can’t remember practicing with any man other than Jim Mulvaney, perhaps because he was the only one of my boyfriends I considered marrying. That’s the good news. The bad news is that he did not like any of the meals I made him. They were not poorly cooked. Just not to his liking. I made him beef bourguignon, thinking what man would not like beef bourguignon. Answer: Jim Mulvaney. I tried something more modern. Quiche. Good quiche. He hated it. Around the same time the book Real_Men_Don’t_Eat_Quiche was published. It was intended to be satire. Jim Mulvaney presumed it was the 11th commandment as issued by his Catholic school nuns.

We went out to dinner a lot after that. Then we moved to Mexico, where the maids put down their straw brooms to cook glorious meals. In Hong Kong, my husband often dismissed our one domestic helper and made dinner because he likes to cook. The men in his family often cooked and still do.

More recently, the introduction of ready-to-cook meal kits that come in boxes has changed my life. These arrive with all the ingredients in small packages and a card with clear instructions. A match made in my own personal heaven on earth. I do not like supermarkets and I love written instructions. I have tried three different brands of these boxes and made some delicious meals, gobbled up by my husband. Ever the dreamer, he now thinks I should return to shopping each afternoon for evening meals and making up recipes as I go along. Nope.

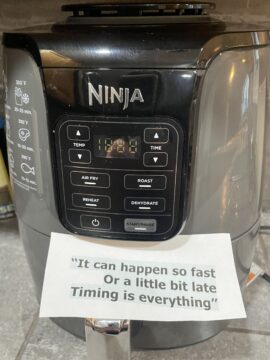

Which brings me back to this past Christmas. I had already used and loved the dutch oven. Encouraged, my husband bought me an air fryer, his blue eyes again aglow. Those eyes will live longer than he does. I had never seen such a contraption. Soon I realized that an air fryer was the moral equivalent of a dustbuster. It is a clumsy robot masquerading as an appliance and more trouble than it is worth. With my mother-in-law long gone, I elevated it to the role of co-culprit.

The air fryer has entered my life on a fraudulent basis. It is supposed to make healthy meals that are not fried. It is also supposed to take the place of an oven. Yet we hardly ever fry any food. I already have an oven I like. Sure the oven has some quirks. But they are quirks I understand. I turn it on in tandem with a fan embedded above it in our microwave to avoid setting off the smoke detector. When my husband uses the oven he forgets—or refuses—to turn on the fan, invariably setting off the aforementioned detector. The sound of its alarm sears the house. My husband then opens many windows, locates a step tool, brandishes a sharp knife and pokes the detector into silence. Then the microwave fan turns on and whirs throughout dinner. Nowadays, I imagine our real oven, as I once imagined a vacuum cleaner, staring across the kitchen at the air fryer, with major disdain.

The air fryer has no self-awareness. Turn it on and its computer instructs you to preheat it for 19-plus minutes. This is too long. Typically, my husband appears in the kitchen after three minutes of pre-heating and announces the preheating is done. This is too short. He then puts a slab of protein inside the air fryer compartment, fish, chicken or whatever (It is significant that he does not do this with steak, his favorite protein.) We keep taking fish or chicken out of the air fryer compartment. It is never done within a reasonable period of time or we leave it in too long and it is overdone. It only works well when cooking small potatoes. Did I mention Mulvaney is of Irish descent? Clearly there is no French—or more accurately Belgian—in his DNA because to make french fries in the air fryer one needs about the same amount of time it would take to write a grant proposal. To make these air fryer fries you need to cut up a large batch of potatoes and then air fry them in countless small batches for a period of time that may or may not work. My husband and I do agree that this is not an efficient way to make french fries. Not that this creates peace at home. We often argue over issues about which we agree.

The air fryer also mucks up my cooking from the boxes. None of the recipes are made for air fryers. My husband says this will change when Martha Stewart and her ilk acquire air fryer companies. I can wait.

I did, by the way, get vindication on the air fryer.

My husband was down a hallway in his home office on the phone with a friend, a brilliant guy who has interrogated some of the major criminals of the twenty-first century. I was in the kitchen trying one last time to be a good sport and cook salmon in the air fryer. I called out to my husband to help me check on the timing, futile though I knew this would be.

As I later heard it, this caused my husband’s friend to let out a long feral moan, one you might hear from the target of an investigation, rather than the investigator himself.

“Geez, what was you thinking,” the interrogator had said. “I told you to ask me before you do something stupid.”

My husband thought, but didn’t say, “how was I supposed to know buying an air fryer was stupid?” It is part of the male code never to say such words aloud. Real men don’t eat quiche—or admit to purchasing errors.

After the phone call ended, I sensed from the look on my husband’s face that there was something I should know.

“What did he say? I asked.

My husband put his hand on the air fryer, with a sympathetic touch. “He said he bought one for the wife for Christmas three years ago. Said it sat on the counter for a couple of weeks, wound up in the closet where it continues to reside. Never produced a meal.”

Now there’s a woman I admire. I bet she never used her dustbuster either.