by Muhammad Aurangzeb Ahmad

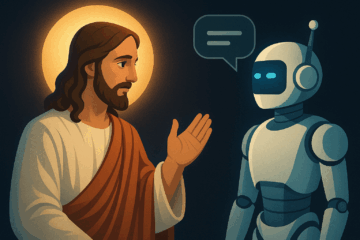

In recent years chatbots powered by large language models have been slowing moving to the pulpit. Tools like QuranGPT, Gita GPT, Buddhabot, MagisteriumAI, and AI Jesus have sparked contentious debates about whether machines should mediate spiritual counsel or religious interpretation: Can a chatbot offer genuine pastoral care? What happens when we outsource ritual, moral, or spiritual authority to an algorithm? And how do different religious traditions respond differently to these questions? Proponents of these innovations see them as tools to democratize scriptural access, personalize spiritual learning, and bring religious guidance to new audiences. Critics warn that they risk theological distortion, hallucinations, decontextualization of sacred texts, and even fueling extremism. Christianity has been among the most visible testbeds for AI-driven spiritual tools. A number of “Jesus chatbots” or Christian-themed bots have emerged, ranging from informal curiosity-driven experiments to more polished, denominationally aligned tools. Consider, MagisteriumAI, which is a Catholic-oriented model intended to synthesize and explain Church teaching. On the Protestant side, an interesting chatbot is Cathy (“Churchy Answers That Help You”), a chatbot built on Episcopal sources that attempts to translate biblical teaching for younger audiences and even serve as a resource for sermon preparation. Muslims are also experimenting with religious chatbots, notables examples include QuranGPT and Ansari Chat. Chatbots answer queries based on the Quran and Hadith, sayings of Prophet Muhammad.

In recent years chatbots powered by large language models have been slowing moving to the pulpit. Tools like QuranGPT, Gita GPT, Buddhabot, MagisteriumAI, and AI Jesus have sparked contentious debates about whether machines should mediate spiritual counsel or religious interpretation: Can a chatbot offer genuine pastoral care? What happens when we outsource ritual, moral, or spiritual authority to an algorithm? And how do different religious traditions respond differently to these questions? Proponents of these innovations see them as tools to democratize scriptural access, personalize spiritual learning, and bring religious guidance to new audiences. Critics warn that they risk theological distortion, hallucinations, decontextualization of sacred texts, and even fueling extremism. Christianity has been among the most visible testbeds for AI-driven spiritual tools. A number of “Jesus chatbots” or Christian-themed bots have emerged, ranging from informal curiosity-driven experiments to more polished, denominationally aligned tools. Consider, MagisteriumAI, which is a Catholic-oriented model intended to synthesize and explain Church teaching. On the Protestant side, an interesting chatbot is Cathy (“Churchy Answers That Help You”), a chatbot built on Episcopal sources that attempts to translate biblical teaching for younger audiences and even serve as a resource for sermon preparation. Muslims are also experimenting with religious chatbots, notables examples include QuranGPT and Ansari Chat. Chatbots answer queries based on the Quran and Hadith, sayings of Prophet Muhammad.

Buddhist communities have experimented with robot monks and chatbots in unique ways. In China, Robot Monk Xian’er, developed by Longquan Monastery, is a humanoid chatbot and robot that can recite sutras, respond to emotional questions, and engage with people online via social platforms like WeChat and Facebook. In Japan, Mindar, an android representing the bodhisattva Kannon, delivers sermons on the Heart Sutra at the Kodai-ji temple in Kyoto. Though Mindar is not powered by AI-driven LLMs, its presence as a robotic preacher raises similar questions about the role of automation in religious ritual. Buddhist approaches to AI and generated sacred texts are often more flexible. In the Hindu context, there is Gita GPT which is trained on the Bhagavad Gita, which users can query for moral or spiritual guidance. Similarly, there are efforts to build chatbots modeled on Confucian texts or other classical religious/philosophical traditions. Scientific American lists a Confucius chatbot and a Delphic oracle chatbot, suggesting that the ambition to create dialogue-based spiritual guides via LLMs extends beyond monotheistic religions. Beyond chatbots that use religious texts or styles, there is the phenomenon of AI as a subject of worship. The short-lived Way of the Future, founded by engineer Anthony Levandowski, proposed that a sufficiently advanced superintelligent AI could function as a deity or “Godhead,” and that it could be honored and aligned with as part of humanity’s spiritual trajectory. Even though, the organization was dissolved in 2021, it remains a provocative example of how deeply entwined questions of technology and divinity can become. Read more »

In the game of chess, some of the greats will concede their most valuable pieces for a superior position on the board. In a 1994 game against the grandmaster Vladimir Kramnik, Gary Kasparov sacrificed his queen early in the game with a move that made no sense to a middling chess player like me. But a few moves later Kasparov won control of the center board and marched his pieces into an unstoppable array. Despite some desperate work to evade Kasparov’s scheme, Kramnik’s king was isolated and then trapped into checkmate by a rook and a knight.

In the game of chess, some of the greats will concede their most valuable pieces for a superior position on the board. In a 1994 game against the grandmaster Vladimir Kramnik, Gary Kasparov sacrificed his queen early in the game with a move that made no sense to a middling chess player like me. But a few moves later Kasparov won control of the center board and marched his pieces into an unstoppable array. Despite some desperate work to evade Kasparov’s scheme, Kramnik’s king was isolated and then trapped into checkmate by a rook and a knight.

For those of us who classify ourselves as Nones—

For those of us who classify ourselves as Nones—