by Ashutosh Jogalekar

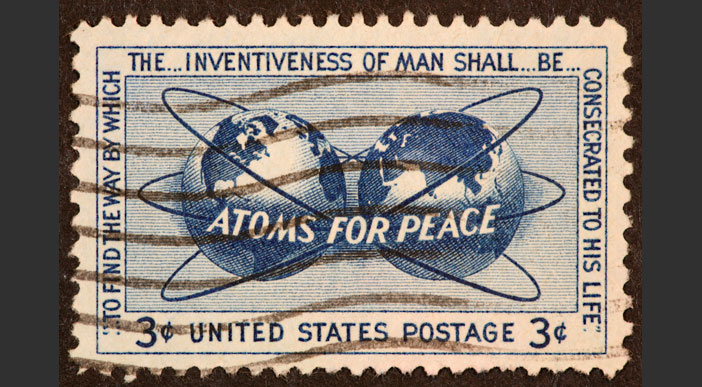

The visionary physicist and statesman Niels Bohr once succinctly distilled the essence of science as “the gradual removal of prejudices”. Among these prejudices, few are more prominent than the belief that nation-states can strengthen their security by keeping critical, futuristic technology secret. This belief was dispelled quickly in the Cold War, as nine nuclear states with competent scientists and engineers and adequate resources acquired nuclear weapons, leading to the nuclear proliferation that Bohr, Robert Oppenheimer, Leo Szilard and other far-seeing scientists had warned political leaders would ensue if the United States and other countries insisted on security through secrecy. Secrecy, instead of keeping destructive nuclear technology confined, had instead led to mutual distrust and an arms race that, octopus-like, had enveloped the globe in a suicide belt of bombs which at its peak numbered almost sixty thousand.

But if not secrecy, then how would countries achieve the security they craved? The answer, as it counterintuitively turned out, was by making the world a more open place, by allowing inspections and crafting treaties that reduced the threat of nuclear war. Through hard-won wisdom and sustained action, politicians, military personnel and ordinary citizens and activists realized that the way to safety and security was through mutual conversation and cooperation. That international cooperation, most notably between the United States and the Soviet Union, achieved the extraordinary reduction of the global nuclear stockpile from tens of thousands to about twelve thousand, with the United States and Russia still accounting for more than ninety percent.

A similar potential future of promise on one hand and destruction on the other awaits us through the recent development of another groundbreaking technology: artificial intelligence. Since 2022, AI has shown striking progress, especially through the development of large language models (LLMs) which have demonstrated the ability to distill large volumes of knowledge and reasoning and interact in natural language. Accompanied by their reliance on mountains of computing power, these and other AI models are posing serious questions about the possibility of disrupting entire industries, from scientific research to the creative arts. More troubling is the breathless interest from governments across the world in harnessing AI for military applications, from smarter drone targeting to improved surveillance to better military hardware supply chain optimization.

Commentators fear that massive interest in AI from the Chinese and American governments in particular, shored up by unprecedented defense budgets and geopolitical gamesmanship, could lead to a new AI arms race akin to the nuclear arms race. Like the nuclear arms race, the AI arms race would involve the steady escalation of each country’s AI capabilities for offense and defense until the world reaches an unstable quasi-equilibrium that would enable each country to erode or take out critical parts of their adversary’s infrastructure and risk their own. Read more »

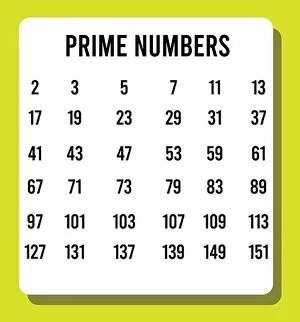

Prime numbers are the atoms of arithmetic. Just as a water molecule can be broken into two hydrogen and one oxygen atoms, 12 can be broken into two 2s and a 3. Indeed, the defining feature of a prime number is that it cannot be factored into a nontrivial product of two smaller numbers. Two primes that are easy to remember are

Prime numbers are the atoms of arithmetic. Just as a water molecule can be broken into two hydrogen and one oxygen atoms, 12 can be broken into two 2s and a 3. Indeed, the defining feature of a prime number is that it cannot be factored into a nontrivial product of two smaller numbers. Two primes that are easy to remember are

When I was growing up, my mother and I would sometimes read or recite poetry to each other. Ours was not a poetic household, and my father would occasionally complain: “If poets have something to say, why don’t they just say it?” But we thought they did say it, albeit indirectly sometimes, and we continued with our Longfellow, a bit more quietly.

When I was growing up, my mother and I would sometimes read or recite poetry to each other. Ours was not a poetic household, and my father would occasionally complain: “If poets have something to say, why don’t they just say it?” But we thought they did say it, albeit indirectly sometimes, and we continued with our Longfellow, a bit more quietly.

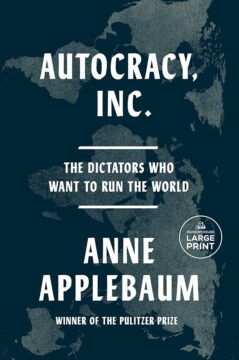

Renowned and respected for her scholarship, her history of authorship of many books on dictatorship and her political experience, is it any wonder that Anne Applebaum’s new book Autocracy, Inc. The Dictators Who Want to Run the World has been so critically received; she is an expert on her subject. This slim volume provides us with an incisive exposition and analysis of how autocrats function in the world today, securing their own personal power and wealth, and in Applebaum’s view, posing a threat to democracies.

Renowned and respected for her scholarship, her history of authorship of many books on dictatorship and her political experience, is it any wonder that Anne Applebaum’s new book Autocracy, Inc. The Dictators Who Want to Run the World has been so critically received; she is an expert on her subject. This slim volume provides us with an incisive exposition and analysis of how autocrats function in the world today, securing their own personal power and wealth, and in Applebaum’s view, posing a threat to democracies.

Every time I read or watch anything about the election I hear some variant of the phrase “margin of error.” My mathematically attuned ears perk up, but usually it’s just a slightly pretentious way of saying the election is very close or else that it’s not very close. Schmargin of error might be a better name for metaphorical uses of the phrase.

Every time I read or watch anything about the election I hear some variant of the phrase “margin of error.” My mathematically attuned ears perk up, but usually it’s just a slightly pretentious way of saying the election is very close or else that it’s not very close. Schmargin of error might be a better name for metaphorical uses of the phrase. Philosophical reflection on artificial intelligence (AI) has been a feature of the early days of cybernetics, with Alan Turing’s famous proposals on the notion of intelligence in the 1950s rearming old philosophical debates on the man-system or man-machine and the possibly mechanistic nature of cognition. However, AI raises questions on spheres of philosophy with the contemporary advent of connectionist artificial intelligence based on deep learning through artificial neural networks and the prodigies of generative foundation models. One of the most prominent examples is the philosophy of mind, which seeks to reflect on the benefits and limits of a computational approach to mind and consciousness. Other spheres of affected philosophies are ethics, which is confronted with original questions on agency and responsibility; political philosophy, which is obliged to think afresh about augmented action and algorithmic governance; the philosophy of language; the notion of aesthetics, which has to take an interest in artistic productions emerging from the latent spaces of AIs and where its traditional categories malfunction; and metaphysics, which has to think afresh about the supposed human exception or the question of finitude.

Philosophical reflection on artificial intelligence (AI) has been a feature of the early days of cybernetics, with Alan Turing’s famous proposals on the notion of intelligence in the 1950s rearming old philosophical debates on the man-system or man-machine and the possibly mechanistic nature of cognition. However, AI raises questions on spheres of philosophy with the contemporary advent of connectionist artificial intelligence based on deep learning through artificial neural networks and the prodigies of generative foundation models. One of the most prominent examples is the philosophy of mind, which seeks to reflect on the benefits and limits of a computational approach to mind and consciousness. Other spheres of affected philosophies are ethics, which is confronted with original questions on agency and responsibility; political philosophy, which is obliged to think afresh about augmented action and algorithmic governance; the philosophy of language; the notion of aesthetics, which has to take an interest in artistic productions emerging from the latent spaces of AIs and where its traditional categories malfunction; and metaphysics, which has to think afresh about the supposed human exception or the question of finitude. The opening credits of Affliction (1997) feature small, rectangular images that fill only half the screen. You wonder if something is wrong with the aspect ratio, or if the settings have been changed on your television. A succession of images is placed before the viewer: a farmhouse in a snowy field, a trailer with a police cruiser parked in front, the main street of a small, sleepy town, the schoolhouse, the town hall. The last image is a dark, rural road, with a mountain in the distance. Finally the edges of the image expand, fill the screen, and a voice begins to narrate:

The opening credits of Affliction (1997) feature small, rectangular images that fill only half the screen. You wonder if something is wrong with the aspect ratio, or if the settings have been changed on your television. A succession of images is placed before the viewer: a farmhouse in a snowy field, a trailer with a police cruiser parked in front, the main street of a small, sleepy town, the schoolhouse, the town hall. The last image is a dark, rural road, with a mountain in the distance. Finally the edges of the image expand, fill the screen, and a voice begins to narrate: