by Mark Harvey

Most people don’t want to hear your sob stories, even if they pretend to be caring listeners. Even a good friend listening to your personal version of Orpheus and Eurydice—and making all the right noises—is probably focused on whether to put snow tires on their car Thursday or Friday.

Some of us turn to music to ease our mortal wounds and it’s a bit of a mystery as to why sad music is actually helpful. I turn to either classical or country music when I need to feel better about a loss or when things just won’t go my way. There is a vast distance between the ultra-cultured notes of, say, the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra and the decidedly baseborn lyrics of the country songsters I like. But lo and behold, each can have its healing powers, and a little of each might be the key to a good diet.

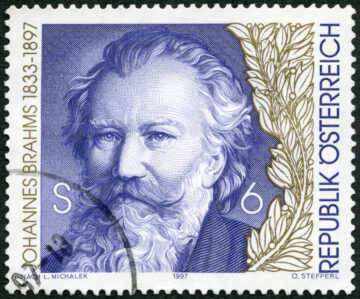

You can hear the grand wounds and the bending of the Weltgeist in classical music and it often involves losing a village or watching Napoleon fail at taking Russia. The great composers endeavor to capture tidal movements and tidal emotions. They have a whole orchestra with bizarre instruments such as glockenspiels and contrabassoons, to accompany the more common violins and pianos. To play in a great orchestra takes merely 15 years of daily practice from the age of four along with some otherworldly talent. So if you wake up feeling sad about the fall of democracy in Europe, by all means, reach for your Schubert or your Brahms. That’s what it takes to handle the bigger themes.

Country music is less ambitious and more concerned with things like, “Whose bed have your boots been under? And whose heart did you steal I wonder?”. But when you’re in the throes of a tawdry breakup, the clever, brassy lyrics of a Shania Twain or a Jamie Richards might offer the fast, powerful relief you need and can’t get from the refined classical music.

Good country music has the boomy-bassy-twangy sound made by simple instruments such as slide guitars, fiddles, and banjos. It can be plaintive and crooning but part of what makes it successful are clever, ironic lyrics.

Take Jamie Richards’s song Don’t Try to Find Me. Presumably, after a tough breakup, he advises his girlfriend not to try to find him,

At the Holiday Inn in Dallas

The one off L B J

You can see the sign from the freeway

Exit 19A

At the end of the hall on the top floor

Overlooking the pool 3 0 4

That’s probably where I’m gonna be

So don’t try to find me

What’s helpful about Richards’ song is that it captures the pathos of a broken heart and the ridiculous longing to get back together without losing face. We’ve all been there.

George Jones sings about the same thing in his song, She Thinks I Still Care:

Just because I asked a friend about her

Just because I spoke her name somewhere

Just because I rang her number by mistake today

She thinks I still care

Just because I haunt the same old places

Where the memory of her lingers everywhere

Just because I’m not the happy guy I used to be

She thinks I still care

What the two songwriters manage to do in clinical-speak is called reframing the issue. Instead of drowning in gin and self-pity, the jilted can have a laugh at themselves and their misery—probably still drowning in gin. But knowing that some poor son-of-a-bitch went through what you’re going through and lived to write a funny hit single about the whole business helps.

Classical music is different. It goes right for the throat and doesn’t have much time for irony. It’s about the clavichord, not the clever. If you listen to the really melancholic pieces after a breakup, you may be taking the breakup too seriously. You lost a girl or a guy, not half of Europe. Your girl’s boots were under a bed not your own, but Western Russia is not in the midst of a famine. Grow up and turn off that Intermezzo in A Major.

The melancholic classical music does have its place even for those of us not embodying Hegel’s Weltgeist—those of us who are not the great men or women bending history to our will. Life can ultimately be quite sad and much of life is about loss, especially as we get older. Supposedly Johannes Brahms wrote Intermezzo in A Major as a love letter to Clara Schumann, the wife of the great composer Robert Schumann. Schumann was Brahm’s idol and mentor and he formed a strong bond to both the composer and his wife. When Schumann began to lose his mind and was placed in a sanatorium, Brahms became ever closer to Clara, and began a lifelong correspondence of love letters. Being in love with the wife of his idol was torture to Brahms, and it drove him to contemplate suicide.

Scholars speculate that Intermezzo in A Major was both a love letter to Clara and a wistful reflection on aging and mortality. I can’t find any direct evidence of that, but the music has the weight and power to address both of those themes. Having just said the piece is a bit much to soothe a broken love affair, anyone who can compose like Brahms probably had the expansive emotions to match his own music.

Gustav Mahler wrote his Fifth Symphony while suffering from heart disease and after losing his oldest daughter. He had suffered a number of losses, including the early deaths of several siblings, and he was tormented by the antisemitism of Austria at the time. Again, I can’t find any direct evidence, but scholars suggest his Fifth Symphony was a reflection on the loss of his daughter and his own mortality. Some cite the “fading adagio” in the later part of the piece as his farewell to life.

My technical knowledge of classical music is about as advanced as you’d expect from a guy who listens to lots of country music: extremely limited. I had to google “fading adagio.” But it doesn’t take a prodigy to know that Brahms and Mahler and the other greats were dealing with the bigger themes in life such as true love, loss, and death—and, yes, sometimes Napleon being defeated by Russia, as in the case of Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture. In my days of listening to the stuff, I haven’t found many trifling pieces by the great composers. Even Beethoven’s Bagatelles (which means trifle in French) are so beautifully put together that they can move all but the most hardened.

The late Polish poet and novelist Adam Zagajewski describes hearing Mahler’s Fifth Symphony for the first time as a young boy while still living in what is today western Ukraine. He wrote,

…when I heard the first movement, the trumpet and the march, which was at the same time, immensely tragic, and a bit joyful too, or at least potentially joyful, I knew from this unexpected conjunction of emotions that something very important had happened: a new chapter in my musical life had opened and in my inner life as well.

Years later, a British conductor told Zagajewski that the Fifth Symphony was probably “a bit too popular, too accessible, too easy” to be taken seriously by true musicians. I don’t find any Mahler music to be too accessible or too easy and in fact find quite a bit of it is beyond my understanding. Take Mahler’s Seventh Symphony….please. It begins quite darkly with a solo horn and is then joined by the rest of the orchestra in what to me sounds like the beginning of a pretty unpleasant journey, perhaps running from something unnamed and probably uncurable. The rest of the symphony is all over the map—to my untrained ear—and frankly confusing. The music critics say it’s got a bit of allegro risoluto, ma non troppo and lots of scherzos. Again, I had to look up these terms and scherzo in Italian means jest or joke. In the Seventh Symphony, all the sherzos went over my head.

Besides, I like my music a little on the accessible side and country music is if nothing else, accessible. Plus it’s got lots of good sherzos.

Just in case Jamie Richard’s ex-girlfriend fails not to find him at the Holiday Inn in Dallas in room 304 overlooking the swimming pool, he suggests other places where she should not try to find him such as,

At my momma’s house in Houston

Just off of Wayside Drive

At the high school hang a right

Last one on the left-hand side

There’s a fence with a rusty old gate

Broken mailbox 108

That’s probably where I’m gonna be

So don’t try to find me

Country music is rich with clever, accessible lyrics that convey situations even more pathetic and ridiculous than your own lonely heart and damn it’s good to know about how the singer Chuck Mead’s ex “got the ring and he got the finger” or about how Jerry Reed’s ex “got the gold mine and he got the shaft.” Jimmy Buffet (considered Gulf and Western) advises his ex that “if the phone doesn’t ring, it’s me.” After noting “that this trailer stays wet, and we’re swimming in debt,” Deana Carter asks, “Did I shave my legs for this?”

I keep my love of classical music a secret from my cowboy friends. Bad enough that I own a Toyota Forerunner. I don’t confess to my friends with graduate degrees that I think Jamie Richards is a lyrical genius and insist that you really have to listen to Don’t Try to Find me several times to appreciate its full scope.

I keep my love of classical music a secret from my cowboy friends. Bad enough that I own a Toyota Forerunner. I don’t confess to my friends with graduate degrees that I think Jamie Richards is a lyrical genius and insist that you really have to listen to Don’t Try to Find me several times to appreciate its full scope.

Those worlds, I hope, never the twain shall meet.