by Eric Feigenbaum

Two of the most frightening words in America: Medical Debt. And this nightmare is not just something you hear as an anecdote or cautionary tale. One in three of the people reading these words are likely to have medical debt.

In 2022 roughly 100 million Americans – almost one-third of the population – were saddled with healthcare debt. Yet, more than 90 percent of Americans have some form of health insurance – because it’s less frequently a problem of being uninsured, but underinsured that puts people behind the eight ball. Unsurprisingly, when a problem is so impactful and pervasive, at least some members of the media turn their attention to it.

ProPublica journalist Marshall Allen has been researching and writing about medical bills for more than 20 years – following up on readers’ emails and exploring their medical debt stories. From hospitals that gouge to insurance that is unknowingly cancelled because a credit card wasn’t processed correctly, the ways Americans find themselves paying for their most difficult, painful and vulnerable moments are innumerable. And for whatever kindness they may have received when getting treatment, the billers and collections agents who follow can be heartless.

As a result, many developed countries hold America up as the model of what they don’t want in a healthcare system. The thinking is that healthcare is a human right, not a luxury.

The problem in the American system isn’t typically the quality of care – we have some of the best medical facilities in the world along with cutting edge treatments and technology. It’s that the patient can’t typically control the costs. In the midst of needing life-saving medical care, neither patient, patient’s family nor medical providers can or should consider cost.

Only when a car accident or heart attack drives the patient $100,000 into debt, something has gone terribly wrong. Read more »

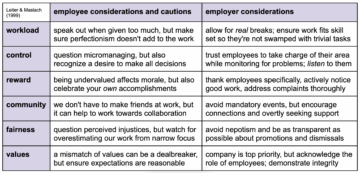

I started reading about burnout when I walked away from teaching earlier than expected. Suddenly, I couldn’t bring myself to open that door after over thirty years of bounding to work. A series of events wiped away any sense of agency, fairness, or shared values. Their wellness lunch-and-learns didn’t help me, and I soon discovered I’m not alone.

I started reading about burnout when I walked away from teaching earlier than expected. Suddenly, I couldn’t bring myself to open that door after over thirty years of bounding to work. A series of events wiped away any sense of agency, fairness, or shared values. Their wellness lunch-and-learns didn’t help me, and I soon discovered I’m not alone.

Eugene Russell, a piano tuner interviewed by

Eugene Russell, a piano tuner interviewed by

Sughra Raza. Untitled. June, 2014.

Sughra Raza. Untitled. June, 2014.

In philosophical debates about the aesthetic potential of cuisine, one central topic has been the degree to which smell and taste give us rich and structured information about the nature of reality. Aesthetic appreciation involves reflection on the meaning and significance of an aesthetic object such as a painting or musical work. Part of that appreciation is the apprehension of the work’s form or structure—it is often the form of the object that we find beautiful or otherwise compelling. Although we get pleasure from consuming good food and drink, if smell and taste give us no structured representation of reality there is no form to apprehend or meaning to analyze, so the argument goes. The enjoyment of cuisine then would be akin to that of basking in the sun. It is pleasant to be sure but there is nothing to apprehend or analyze beyond an immediate sensation.

In philosophical debates about the aesthetic potential of cuisine, one central topic has been the degree to which smell and taste give us rich and structured information about the nature of reality. Aesthetic appreciation involves reflection on the meaning and significance of an aesthetic object such as a painting or musical work. Part of that appreciation is the apprehension of the work’s form or structure—it is often the form of the object that we find beautiful or otherwise compelling. Although we get pleasure from consuming good food and drink, if smell and taste give us no structured representation of reality there is no form to apprehend or meaning to analyze, so the argument goes. The enjoyment of cuisine then would be akin to that of basking in the sun. It is pleasant to be sure but there is nothing to apprehend or analyze beyond an immediate sensation.

Bill Gates has long been one of the world’s leading optimists, and his new documentary, “What’s Next,” serves as a testament to his hopeful vision of the future. But what makes Gates’s optimism particularly compelling is that it is grounded not in dewy-eyed hopes and prayers but in logic, data, and an unshakable belief in the power of science and technology. Over the years, Gates and his wife Melinda, through their foundation, have invested in a wide array of innovative technologies aimed at addressing some of the most pressing issues faced by humanity. Their work has had an especially transformative impact on underserved populations in regions like Africa, tackling fundamental challenges in healthcare, energy, and beyond. In this new, five-part Netflix series, Gates showcases his trademark pragmatism and curiosity as he engages with some of the most complex and important challenges of our time: artificial intelligence (AI), misinformation, inequality, climate change, and healthcare. His approach stands out especially for his willingness to have a dialogue with those with whom he might strongly disagree.

Bill Gates has long been one of the world’s leading optimists, and his new documentary, “What’s Next,” serves as a testament to his hopeful vision of the future. But what makes Gates’s optimism particularly compelling is that it is grounded not in dewy-eyed hopes and prayers but in logic, data, and an unshakable belief in the power of science and technology. Over the years, Gates and his wife Melinda, through their foundation, have invested in a wide array of innovative technologies aimed at addressing some of the most pressing issues faced by humanity. Their work has had an especially transformative impact on underserved populations in regions like Africa, tackling fundamental challenges in healthcare, energy, and beyond. In this new, five-part Netflix series, Gates showcases his trademark pragmatism and curiosity as he engages with some of the most complex and important challenges of our time: artificial intelligence (AI), misinformation, inequality, climate change, and healthcare. His approach stands out especially for his willingness to have a dialogue with those with whom he might strongly disagree. I lived in Philadelphia in 1977 and would go to the Gallery mall on Market Street, a walking distance from our river front apartment. One day, around lunch, I decided to get Chinese food at the food court and looking for a place to sit, I asked two older ladies if I could sit at their table, since the place was packed. As I was picking through the food, separating the celery and water chestnuts, one of the old ladies said

I lived in Philadelphia in 1977 and would go to the Gallery mall on Market Street, a walking distance from our river front apartment. One day, around lunch, I decided to get Chinese food at the food court and looking for a place to sit, I asked two older ladies if I could sit at their table, since the place was packed. As I was picking through the food, separating the celery and water chestnuts, one of the old ladies said