by David J. Lobina

Firstly: fascism is dead and it is not coming back. By fascism it is meant the historical fascism of the 1920-40s, in particular the primus inter (more-or-less) pares fascism of 1920s Italy – id est, Fascism – and to a lesser extent that of Nazi Germany, notwithstanding the fact that Nazism is different to Fascism in some important respects, as stressed before in these very pages – alas not being the case here, secondes pensées sont (often) les bonnes.

Secondly: this is not our opinion alone, but that of both Umberto Eco, explicitly stated so in his little note on fascism, and Pier Paolo Pasolini, the latter saying so-so in a little-known pamphlet by the title of Il fascismo degli antifascisti. For the latter author, historical fascism was the traditional or archaeological kind, an archaic fascism that did not exist any more at the time of writing (circa 1960-1975) and should not be confused with the fascism that 1960-70s kids kept denouncing, and the Owen Joneses of the 2020s keep denouncing, this milieu then and now forming an archaeological antifascism that is rather comfortable, as Pasolini put it then. For the former author, in turn, historical fascism was the original kind, and also dead, but there was a warning therein: an eternal fascism can be unearthed in terms of the fascist ‘way of talking and feeling’ – the linguistic habits of fascism.

Thirdly: what the Eco of the little note was most concerned about was the then contemporary developments in Italian politics that had brought a post-fascist political party into government in 1994. In this note Eco listed a number of features encompassing what may be termed a fascist temperament, a loose connection of features that has received little attention in the scholarship on fascism – the world of the discretus et sapiens – but an outsized interest elsewhere. Eco did not envision this list as a set of necessary or sufficient conditions to define fascism; nothing so unambitious: one single feature sufficed ‘to allow fascism to coagulate around it’, a sentiment widely echoed today.

Fourthly: Fascism, however, is not a way of talking or feeling, or a temperament, let alone an eternal phenomenon, in the same way that there is no eternal communism, or a communist way of talking or feeling; no eternal liberalism, or a liberal way of talking or feeling; no eternal anarchism, or an anarchist way of talking or feeling. The Okhrana is reputed to have dismissed the stereotypically-looking revolutionaries, and rightly so; the same applies, mutatis mutandis, in the state of affairs being surveyed by our telescope.

Fifthly: there might be some eternal concepts, at least in the evolutionary sense that the human species is rather young in the history of the world, and human cognition being the way it is, some beliefs and desires can arise at different times in history, and similar thoughts can also manifest themselves in different centuries given the right environmental conditions, many generations removed (within reason). A linguistic analogy will help make or break the point, this time connecting to the potentialities of behaviour, a Part 2 to that Part 1.

Sixthly: there is a distinction to be had, according to Noam Chomsky, between the capacity for language, which is universal and thus shared by every member of the human species, and this includes the humans of 50,000 years ago, and the particular realisations of this capacity – that is, the particular languages that arise in specific places and at specific times in history, for whatever reason. This point has come up quite often in the last 10-15 years in relation to the Pirahã language, which is claimed to lack some features that are present in almost every other language (e.g., a number system, subordinate sentences, etc.) – the claim may be correct (or not), but the point of many a linguist to the presented evidence has been forthcoming as such: even if some properties have not been realised in this language, that does not mean they are not part of the language faculty, and of the faculty of Pirahã speakers too. No-one, after all, has ever claimed that every feature the language faculty allows for will be present in every language (not every language is a tonal language, for instance); whether a particular feature is realised or not is often a matter of circumstance or even chance.

Seventhly: likewise, then, plausibly, regarding the capacity to have political ideas and beliefs, and to engage in debates about one’s economic and political situation. Such a capacity may be a universal feature of homo sapiens as much as language is, but how the capacity has been realised in human history would depend on the actual circumstances at each time and it is not a given (nay, it is unlikely) that the concerns people had 100 years ago would bear all that close a resemblance to the concerns of present societies.

Eighthly: historical movements have their own historical moment, which is to say that they are the product of the circumstances in which these movements arose and develop – every historical process moves suo moto, after all. Interwar Europe was the result of an interwar period: there was plenty of unfinished business after the Great War, with plenty of ex-soldiers wanting to rerun the war, becoming militias, squadristi and part of the Freikorps; there were uprisings of different political signs, and reactions to these; there was brutal deflation, long depressions, and joblessness; there was imperialism; there was the war economy; there was the proletariat and political organisations, with militia-parties, and also modern mass parties. In sum, and to summarise an editorial of the New Left Review, fascism (in the loose sense, and encompassing both Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany) was the product of inter-imperial warfare, a capitalist crisis of a specific kind, and the threat of revolution – a different world altogether.

Ninthly: Fascism is thus a historical phenomenon, not a way of talking or feeling, or a temperament, and the phenomenon is not to be defined by a list of features or characteristics. It is best defined, as per a definition of Emilio Gentile, via a Google translation from the original in Italian, a translation retaken from here (endnote viii), as:

a modern political phenomenon, nationalistic and revolutionary, anti-liberal and anti-Marxist, organized in a “militia party”, with a totalitarian conception of politics and the state, with a mythical, virilistic and anti-hedonistic ideology, consecrated as a secular religion, which affirms the absolute primacy of the nation, understood as an ethnically homogeneous organic community, hierarchically organized in a corporate state, with a warlike vocation for the politics of greatness, power and conquest, aimed at the creation of a new order and a new civilization.

Tenthly: naturally, some of the elements from the Gentile definition may have precursors in different previous epochs, and these might reappear, in some form or other, in the future too, but the correspondences are likely to be fairly superficial and far too loose. It is the confluence of conditions and events that make a given phenomenon a historical phenomenon to begin with, all of it its own and whole. Thus put, and just as it is nonsensical to talk of an eternal fascism, it is also wrongheaded to see fascism as a dynamic that precedes its naming, as Alberto Toscano claims in his Late Fascism book – not quite fascism being a phenomenon ante litteram, but in fact, supra mundum too. A rather tendentious take on fascism, and supposedly a Marxist view of the phenomenon, and therefore, drawing too close a connection between fascism and capitalism than the historical record clearly merits, the eventual result is a view that is to a great extent based on racial and racist fantasies of national rebirth – and, thus, closer to Nazism than to Fascism, but even so, only superficially so. A common malaise these days, alas.

Eleventhly: the current obsession with identifying various contemporary political currents and undercurrents as Fascism – that is, as phenomena that are directly connected to 1920-40s Europe, and not simply a case of using the word ‘fascism’ to refer to authoritarian regimes (common enough, but perhaps misguided and best left to demo slogans) – belies an unhealthy propensity to broaden the term fascism far too broadly, weak to non-existent connections to historical fascism in view and little more.

Twelfthly: the point is to understand political phenomena, both in the past and in the present; weak analogies will not do, and they certainly will not aid in dealing with present dangers. As point Eight supra alluded to, actors need to be placed in the right domestic context for elucidation. To take the US as a case in point, and with the focus squarely on the conditions now faced: there is stagnation and profit, but low wages; low unemployment compared to 1920s Europe; no Great War; the atomisation of precarious working conditions, compounded by globalisation; no paramilitary blocs, let alone paramilitary parties, e così via.

Thirteenthly: there have always been wannabe dictators and populists, but the comparisons with historical figures from the past only hold under rather dubious terms of comparison. A certain political candidate in the US – some misguidedly call him a Tangerine Mussolini, even though the right analogy would be as a Tangerine (Silvio) Berlusconi – may sound a bit like fascists of lore at times, but this is more imitation than a show of true character – a parroting and mimicking of expressions and phrases, not a continuum of any kind.

Fourteenthly: it is unclear what the purpose of running so hard the line that fascism is so present and so widely is, with whole sections of various newspapers devoted to the phenomenon, often more a potpourri of ideas and reportage than proper analysis. It is possible the purpose is to dehumanise, and thus make certain parties and characters beyond the pale, stuff to not be attended to. This is bad scholarship and manipulative, and liable to be counterproductive.

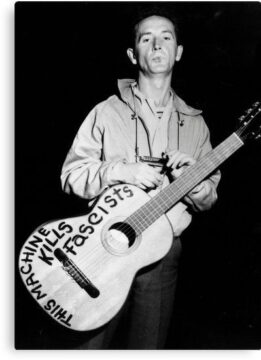

And Fifteenthly: real fascism was fought on the battlefield in the 1920-40s, and real rifles were used for this purpose by once famous singers. Whatever happens in the forthcoming US election, we are likely to see more riots than Matteottis; these are the times we live.

NB: The minutes shall reflect that a case was made that Fascism is back and on the ascendancy everywhere in the world, and that the arguments were thoroughly refuted.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.