by Brooks Riley

Richard Wagner’s mammoth Ring of the Nibelung cycle begins with a single note—not a chord, or series of notes, or leitmotif—but an extended E flat so deep it could be mistaken for noise, or the rumblings of Earth giving birth to tragedy. Hours later, this Ur sound, produced by eight contrabassi over four measures, will hardly be remembered after so many other sounds have competed for the listener’s attention. But the effect lingers on, deep in the psyche.

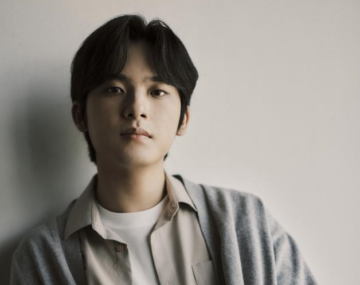

Someone else who understands the power of a single note is pianist Yunchan Lim, winner of the 2022 Van Cliburn competition at age 18, who electrified the classical music community with his performances of Rachmaninoff’s Concerto No. 3 and Liszt’s Transcendental Études and has since sold out concerts around the world. His reputation for virtuoso barrages of perfect notes at dizzying speeds belies a deep engagement in the sound he can extract from the piano with a single note—a process he demonstrated in an interview for Korean television last May.

Someone else who understands the power of a single note is pianist Yunchan Lim, winner of the 2022 Van Cliburn competition at age 18, who electrified the classical music community with his performances of Rachmaninoff’s Concerto No. 3 and Liszt’s Transcendental Études and has since sold out concerts around the world. His reputation for virtuoso barrages of perfect notes at dizzying speeds belies a deep engagement in the sound he can extract from the piano with a single note—a process he demonstrated in an interview for Korean television last May.

‘In my mind, there’s always a feeling of what I think is the truly perfect sound. That sound exists. When the sound in my mind perfectly matches the sound in reality, at that moment, I feel my heart moving.’

As a percussive instrument, the piano is not very malleable. The tone of a single note occurs far from the finger that hits a key to activate a hammer to hit a string. Variety of tone depends on the force with which the finger has hit the key, or where on the key the finger has hit, as well as the use of pedals to amplify and elongate the sound or to mute it. The piano has no vibrato, for which one can be grateful, considering how many other instruments depend on it.

‘. . .when I press the G-sharp key, if it strikes my heart, then I move on to the next one. . .If my heart doesn’t feel it when moving to the A-sharp key, I keep doing it. . . . if the A-sharp key strikes my heart, then I practice connecting the first and second notes, and if that connection strikes my heart, then I move on to the third note.’

This may be one reason why his practice sessions are so long, often late into the night, or why he once spent hours on two measures of a Schubert Sonata. For Lim, technical brilliance is a given. What’s important to him are tone, color, rubato, feeling, poetry, poignancy, interpretation—even if he is wary of sentimentality or too much emotion. Read more »