by Gus Mitchell

The following piece is my own minor contribution to the “Surrealism Centenary.” I begin with a disavowal of the entire “2024 centenary” enterprise, which seems to have added little to our appreciation of the group, and because I would question allowing Andre Breton, great though he sometimes was, to continue to define the wildly heterodox big bang to which he claimed total definition in October 1924.

Let us begin to celebrate the spirit of the surreal again. True to that spirit, let us slough off the burden of officialism and of art history. Let us not be bound to Breton or (heaven help us) Dali any longer.

This year should begin an overhaul of correction to the Anglophone ignorance of the movement’s noblest, most enduring, and still-dangerous representatives, who always were the outcasts, misfits, and weirdos among those proudly self-proclaimed outcasts, misfits, and weirdos.

Of these, a host of obscurer names and out of print-translations can be dug into online.

What I outline here is merely my favourite example.

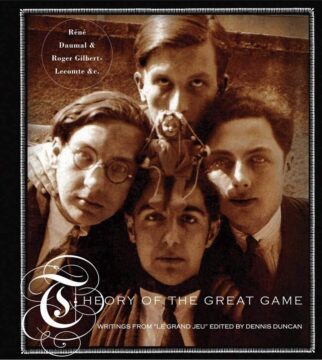

In the 1910s, a quartet of teenaged artistic comrades in provincial France––Rene Daumal, Robert Gilbert-Lecompte, novelist Roger Vailland and Robert Meyrat––began a drug-fuelled quest into what they termed “experimental metaphysics”. After forming something of an adolescent secret society/artistic movement (which they dubbed Simplisme) this core quartet moved to Paris, made some older acquaintances and formed a short-lived journal: Le Grand Jeu (The Great Game) of which only three issues appeared, between 1928 and 1932. (The essence of this work and an essential English handbook to the group can be found in the English translation Theory of the Great Game, edited by Dennis Duncan, pictured above.)

Daumal, like many of the most interesting French surrealists, is almost unknown in the English-speaking world. His most famous work, the allegorical novel Mount Analogue, ends in mid-sentence –– Daumal died of tuberculosis in 1945. In the novel, a group of mountaineers made up of scientists, artists and thinkers are led by a charismatic “Master” – Father Sogol, “Logos” backwards –– seek to climb an invisible mountain, where Heaven and Earth apparently meet, and which can be found only by those who set sail and seek it. Daumal writes in his “Preface”:

Alpinism is the art of climbing mountains by confronting the greatest dangers with the greatest prudence. Art is used here to mean the accomplishment of knowledge in action.

You cannot always stay on the summits. You have to come down again…

“So, what’s the point?” Daumal then asks. Of art, of life, of anything? “Only this: what is above knows what is below, what is below does not know what is above.”

Here is what Daumal’s best friend, Robert Gilbert-Lecompte wrote, around a decade prior to Mount Analogue, in the “Preface” to the inaugural issue of Le Grand Jeu:

The great game is irremediable; it is played only once. We wish to play it every moment of our lives. It is a case of “loser wins”, since the aim is to lose oneself. And we want to win. Yet the Great Game is a game of chance, that is to say of skill, or better still, ‘grace’: the grace of God, and the grace of action […]

All the great mystics of all religion would belong with us if only they had broken the yoke of their religions, to which we cannot submit […]

We are not individualists: instead of locking ourselves up in our past, we walk together united, each carrying his own corpse on his back […]

This is our final communal act; art, literature –– to us these are nothing but a means.

The Grand Jeu group have been neglected, at least in English-speaking history, from the general consciousness of “Surrealism” but they remain among its most interesting dissidents. The teenage Simplistes, led by Daumal and Gilbert-Lecompte, collectively experimented with consciousness and investigated wildly syncretic modes of destroying and recombining selves: diverse hermetic and occult systems, extrasensory perception, trances and somnambulism, mediumistic practice and collective dreaming.

As André Rolland de Renéville, another Grand Jouer, wrote in one issue, to summarise this life and death approach to literary experimentation: “At the point where the poet and mystic meet, at the zero point where the claims of all affirmation and negation cease, the antinomy of contrary realities is effaced through their insight.”

The Jeu’s members mingled and clashed with André Breton, who by 1928 had already outcast such heretical freaks as Bataille and Artaud from the “mainstream” Surrealist movement (surely a rather too-surreal concept, for me.) In March 1928 that Breton called a meeting at the Bar du Chateau in Montparnasse, featuring Man Ray, Magritte, Hans Arp, Louis Aragon, Yves Tanguy, and René Crevel amongst others, to “discuss the possibility of collective action”––uniting the squabbling factions once again. But it turned out to be yet another bagarre surréaliste, aimed squarely at the young upstarts of Le Grand Jeu who stormed out in protest at Breton’s verbal attacks. Thus did Breton end up streamlining the movement––tightening his questionable grip.

Today the bickering and backbiting of all the various Surrealisms looks like the narcissism of small differences. Breton disparaged the Grand Jeu as a project of naïve and dilettantish schoolboys. Breton, Le Grand Jeu, and many other surrealists within an-always heterodox movement, always had far more in common than they had apart. One could view the entire history of Surrealism, from Breton’s 1924 Manifesto as pursuit of the Marveilleux––wonderment, estrangement, a freshness in reality––ultimately, innocence.

Breton himself was deeply interested in mythologies, magic, the occult and the esoteric, as were many others. The use to which early surrealist experiments in automatic creation, for instance, put practices around the séance and other occult discourses as a kind of shortcut-bridge to the irrational and the unconscious while largely disavowing genuine belief in them merely shows that in the action of the imagination the Surreal can be alchemized into Real.

The Grand Jeu was a project of paradox: artistic and ascetic, indulgent and severe, political, and mystical, ecstatic and negating, egoistic and selfless, graceful and violent. It sought to continually weave between collectivity and individuality, of art and life, multiplicity and unity, fed by a brew of political radicalism, inspired by Rimbaud’s germinal poetics of revolt and illumination, a utilitarian embrace of occult traditions and ideas, drug experimentation, Hindu sacred texts (Daumal would become an expert in Sanskrit) and some of Bergson’s philosophy. They were, in their own words, “serious players.” It was a mad mix, and in retrospect, clearly doomed to a short life––so, it turned out, were most its members.

According to both Daumal and Gilbert-Lecompte, the apparent contradiction in the role of the artist and the mystic, the revolutionary and the revelatory, is illusory. Why? Because everything is only process and change, including the work of the artist, which is only “knowledge in action”, just as the Great Game, winning and losing oneself (and God) in life, is only “grace: the grace of God, and the grace of action.” To feel otherwise is a delusion of the ego. The self, the subject, was neither coherent nor consistent: the only constant is change –– something which Deleuze, for one, was later to turn into a rallying cry in his discussion of “schizoanalysis”, calling for the “constant destructive task of disintegrating the normal ego.” “Hence”, Gilbert-Lecompte presses on, “our ideal disposition to question everything at every moment … For us, those frames of constraint which social beings are conditioned to accept have been cracked by an immense surge of innocence…”

The death of this ability to play and imagine new selves, to enlarge the bounds of what we know as “Reality”, is what Le Grand Jeu rebelled against. It is in this sense that Le Grand Jeu, and indeed Surrealism as a whole, is “political” or “revolutionary.” Except that admitting that revolutionary potential would also mean vastly expanding the meaning of the political. We’ve already seen––amply and painfully seeing more every day––the pitfalls of equating self-liberation with liberation dans son intégralité.

The Grand Jeu have been often dismissed by historians of Surrealism as (to use one contemporary’s resonant dismissal) “reclining revolutionaries.” Yet if we hear everywhere and all the time that what we need is more than ever a renewed sense of political imagination, then might not this, ultimately, have something to do with it? Might overcoming “capitalist realism” (merely one resonant catchall among many for the vast hole we are in) involve overcoming capitalism by––in a myriad of senses––also enlarging the parameters of the “Real?”

From one point of view, the Grand Jeu were pushing Surrealism to its conclusions, telling Breton what he was still too much bound up in realism to hear. He seemed to come to the same conclusion nearer the end of his life, however, prophesying that “surreality will reside in reality itself, will be neither superior nor exterior to it…because the container shall also be the contained.”

Rather like the universe itself, Surréalisme began at a time and place it is impossible to date exactly. But it is with us for good now–or at least, it was.

Its spirit is sleeping. Perhaps it will come again. When it does, it might be via that alchemy in which contained and container, art and artist, real and surreal, become one––and freedom is the only thing to which we hold.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.