by Nils Peterson

Galway Kinnell said all good writing has a certain quality in common, “a tenderness toward existence.” I agree and feel that one of the great maladies of our age is the communal loss of this feeling. Wendell Berry says “people exploit what they have merely concluded to be of value, but they defend what they love, and to defend what we love we need a particularizing language, for we love what we particularly know.”

Here’s the first part of a poem of mine:

Rain steady on the roof. Far shore lost. Sea quiet,

gray, introspective – like me, I think, entering

from stage left. This is what we’ve made language for,

to enter the world’s drama as player, not just reflex

towards food or away from the saber-tooth.

So now to the enemy, Word Loss.

Robert Bly in his great anthology News of the Universe recounts and comments on the dreams of Descartes as told by Karl Stern in Flight from Women:

In his third dream some terrifying things happened. A book disappeared from his hand. A book appeared at the end of the table, vanished, and appeared at the other end. And the dictionary, when he checked it, had fewer words in it than it had a few minutes before. I suspect that we are losing some of the words that inhabit the left side; our vocabulary is getting smaller. The disappearing words are probably words such as “mole,” “ocean,” “praise,” “whale,” “steeping,” “bat-ear,” “wooden tub,” “moist cave,” “seawind.”

I thought of this passage when I read this account of the new Oxford Junior Dictionary in a remarkable essay by Robert Macfarlane introducing his new book, Landmarks:

The same summer I was on Lewis [an island in the Hebrides], a new edition of the Oxford Junior Dictionary was published. A sharp-eyed reader noticed that there had been a culling of words concerning nature. Under pressure, Oxford University Press revealed a list of the entries it no longer felt to be relevant to a modern-day childhood. The deletions included acorn, adder, ash, beech, bluebell, buttercup, catkin, conker, cowslip, cygnet, dandelion, fern, hazel, heather, heron, ivy, kingfisher, lark, mistletoe, nectar, newt, otter, pasture, and willow. The words taking their places in the new edition included attachment, block-graph, blog, broadband, bullet-point, celebrity, chatroom, committee, cut-and-paste, MP3 player, and voice-mail. As I had been entranced by the language preserved in the prose‑poem of the “Peat Glossary”, so I was dismayed by the language that had fallen (been pushed) from the dictionary. For blackberry, read Blackberry.

Macfarlane is a British naturalist whose book The Wild Places is a description of his hours and days spent in what is left of the wild. Sometimes the wild is closer than you think. Sometimes remote. It is a remarkable book that I can’t recommend too strongly. His book Landmarks is even more remarkable. It is about the loss of the language of the land that our ancestors who worked closely in it and with it had to describe it. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Meadowstream Afternoon, Maine, 2001.

Sughra Raza. Meadowstream Afternoon, Maine, 2001. By all accounts, Alexandre Lefebvre’s new book,

By all accounts, Alexandre Lefebvre’s new book,  Enjambment is often an invitation to surprise. The line following a deftly deployed line break can serve as an answer to a question; it can, when done well, have an oracular quality, the feeling of a koan. Take for example Cameron Barnett’s powerful poem “Emmett Till Haunts the Library in Money, MS” published in his 2017 collection The Drowning Boy’s Guide to Water. Written in the voice of Till, the fourteen-year-old Black child from Chicago lynched in Mississippi in 1955 whose murder drew attention to anti-Black violence in the United States, Barnett’s poem uses line breaks as a means to defer meaning between stanzas, and thus to generate a heightened sense of awareness. Taking as its conceit the otherworldly haunting of the Money, Mississippi library, a liminal, bardo-like space where Till’s consciousness is able to narrate even after death, the narrator’s individual thoughts are often divided across stanzas, a line break functioning as a type of psychic pause before the thought is completed. For example, in the final line of the first stanza in a three-stanza poem, Barnett writes “Mamie always preached,” completing that thought at the first line of the second stanza with “good posture, so I sit straight at least.”

Enjambment is often an invitation to surprise. The line following a deftly deployed line break can serve as an answer to a question; it can, when done well, have an oracular quality, the feeling of a koan. Take for example Cameron Barnett’s powerful poem “Emmett Till Haunts the Library in Money, MS” published in his 2017 collection The Drowning Boy’s Guide to Water. Written in the voice of Till, the fourteen-year-old Black child from Chicago lynched in Mississippi in 1955 whose murder drew attention to anti-Black violence in the United States, Barnett’s poem uses line breaks as a means to defer meaning between stanzas, and thus to generate a heightened sense of awareness. Taking as its conceit the otherworldly haunting of the Money, Mississippi library, a liminal, bardo-like space where Till’s consciousness is able to narrate even after death, the narrator’s individual thoughts are often divided across stanzas, a line break functioning as a type of psychic pause before the thought is completed. For example, in the final line of the first stanza in a three-stanza poem, Barnett writes “Mamie always preached,” completing that thought at the first line of the second stanza with “good posture, so I sit straight at least.” Books on nature abound. More recently, physicist Helen Czerski’s deep knowledge of the seas functioning as an ‘ocean engine’ in Blue Machine: How the Ocean Shapes the World, elevates our understanding of the ocean and provides us with a new appreciation of its integral role in the Earth’s ecosystem. Volcanologist Tamsin Mather ‘s Adventures in Volcanoland: What Volcanoes Tell Us About the World and Ourselves is also another beguiling journey into the awesome history of the ‘geological mammoths’ that are volcanoes and their dynamics, that have changed the surface of the Earth and impacted on its environment.

Books on nature abound. More recently, physicist Helen Czerski’s deep knowledge of the seas functioning as an ‘ocean engine’ in Blue Machine: How the Ocean Shapes the World, elevates our understanding of the ocean and provides us with a new appreciation of its integral role in the Earth’s ecosystem. Volcanologist Tamsin Mather ‘s Adventures in Volcanoland: What Volcanoes Tell Us About the World and Ourselves is also another beguiling journey into the awesome history of the ‘geological mammoths’ that are volcanoes and their dynamics, that have changed the surface of the Earth and impacted on its environment. Michele Morano: Philip Graham has long been one of my favorite writers to read and to teach because of his insights, humor, and ability to challenge what we think we see. A versatile author of fiction and nonfiction— whose work has appeared in The New Yorker, Paris Review, Washington Post Magazine, McSweeney’s and elsewhere—Graham chooses subjects that explore the rippling surfaces and deep currents of domesticity at home and abroad. Each of his books illustrates Graham’s powers of perception, interpretation, and experimentation, along with his irrepressible interest in people, the more varied and unlike himself, the better. And each has contributed to the perspective of his latest project.

Michele Morano: Philip Graham has long been one of my favorite writers to read and to teach because of his insights, humor, and ability to challenge what we think we see. A versatile author of fiction and nonfiction— whose work has appeared in The New Yorker, Paris Review, Washington Post Magazine, McSweeney’s and elsewhere—Graham chooses subjects that explore the rippling surfaces and deep currents of domesticity at home and abroad. Each of his books illustrates Graham’s powers of perception, interpretation, and experimentation, along with his irrepressible interest in people, the more varied and unlike himself, the better. And each has contributed to the perspective of his latest project.

It’s raining in Russia. Thunderheads boil up in the afternoon heat over there, behind the limestone block fortress on the other side of the river. Which is not a wide river. You can shout across it.

It’s raining in Russia. Thunderheads boil up in the afternoon heat over there, behind the limestone block fortress on the other side of the river. Which is not a wide river. You can shout across it. Sughra Raza. On the Train to Franzensfeste. September, 2024.

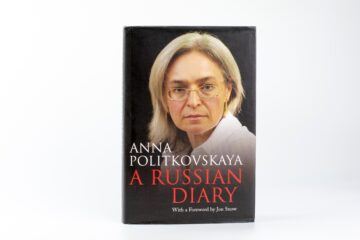

Sughra Raza. On the Train to Franzensfeste. September, 2024. Even if you are sympathetic to Marx — even if, at any rate, you see him not as an ogre but as an original thinker worth taking seriously — you might be forgiven for feeling that the sign at the East entrance to Highgate Cemetery reflects an excessively narrow view of the political options facing us.

Even if you are sympathetic to Marx — even if, at any rate, you see him not as an ogre but as an original thinker worth taking seriously — you might be forgiven for feeling that the sign at the East entrance to Highgate Cemetery reflects an excessively narrow view of the political options facing us.