by John Hartley

With CAPTHCHA the latest stronghold to be breeched, following the heralded sacking of Turing’s temple, I propose a new standard for AI: The Tolkien test.

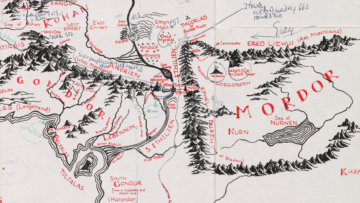

In this proposed schema, AI capability would be tested against what Andrew Pinsent terms ‘the puzzle of useless creation’. Pinsent, a leading authority on science and religion asks, concerning Tolkien: “What is the justification for spending so much time creating an entire family of imaginary languages for imaginary peoples in an imaginary world?”

Tolkien’s view of sub-creation framed human creativity as an act of co-creation with God. Just as the divine imagination shaped the world, so too does human imagination—though on a lesser scale—shape its own worlds. This, for Tolkien, was not mere artistic play but a serious, borderline sacred act. Tolkien’s works, Middle-earth in particular, were not an escape from reality, but a way of penetrating reality in the most acute sense.

For Tolkien, fantasia illuminated reality insofar is it tapped into the metaphysical core of things. The the artistic creation predicated on the creative imagination opened the individual to an alternate mode of knowledge, deeply intuitive and discursive in nature. Tolkien saw this creative act as deeply rational, not a fanciful indulgence. Echoing the Thomist tradition, he viewed fantasy as a way of refashioning the world that the divine had made, for only through the imagination is the human mind capable of reaching beyond itself.

The role of the creative imagination, then, is not to offer a mere replication of life but to transcend it. Here is the major test for AI, for in doing so, it accesses what Tolkien called the “real world”—the world beneath the surface of things. As faith seeks enchantment, so too does art seek a kind of conversion of the imagination, guiding it towards the consolation of eternal memory, what Plato termed ‘anamnesis’.

Moreover, Tolkien’s belief that “creativity was a mark of God’s divine image in man” is echoed in his treatment of myth and fantasy, where the battle between good and evil mirrors salvation history. Tolkien’s Catholic understanding supposes that the world is fundamentally good, and that even in its fallen state, there remains vestiges of divine accessible through the fruit of the artistic imagination.

To create, in Tolkien’s view, is to participate in something sacred. Beyond an expression of the artist’s experience; artistic creation reflects the divine likeness. Through the artistic endeavor, humanity returns to its own divine inception, creating not just for the sake of beauty but as an expression of worship. According to Pinsent, Tolkien’s theory of sub-creation, embodied in his fantasy world and languages, mirrors divine creativity and reflects the freedom and dignity of the human person as made in the divine image.

The question arises, what would it take for AI to replicate Tolkien’s ‘sub creation’? Can AI ever become God-like in the sense it propagates adherents and creates its own knowledge and language system? Yet Tolkien believed that by engaging in creative acts, the artist doesn’t merely witness to the hope of salvation (eucatastrophe), they actually contribute to God’s unfolding creation. Pinsent positions Tolkien’s work as a reflection of Christian vocation, not merely as escapism but as a spiritual work of mercy that aligns with knowing and loving God (as the Catholic raison d’être).

In the same way human creation derives its meaning and significance from its correspondence with the divine ‘creator’, so AI cannot and will not overcome the ability to ‘create’ dissociated from the human ‘creator’. In this schema, AI is twice removed from divine creation (sub sub-creation). AI is definitively utilitarian insofar as it is ordered towards resolution and cannot escape linear time. However far AI evolves, or deviates form an initial trajectory, in response to evolving stimuli, it cannot surpass its own historical origin as a created subsidiary of human intelligence. The implication is that for AI to ‘sub-create’ it must necessarily correspond in some sense to that which conferred/bestowed the original ability to ‘create’.

If AI is predicated on knowledge as consciousness as sense perception, then sentience marks the point a ‘thing’ becomes an ‘intellect’. The intellect, thus conceived in Wittgensteinian terms, is defined by pre-existent criteria to which it’s features bear resemblance. Here the Platonic understanding of the human soul becomes the critical distinction. Human intellect is indelibly linked to the transmigration of the immortal soul. Human intelligence, through the soul, is able to reach beyond itself to transcend the material realm. For AI, the material realm is all there can ever be. AI cannot conceive of the mystery of faith, since it lacks the Imago Dei because it is not made in the divine image. The Russian polymath Pavel Florensky summarized this well:

“In creating a work o f art, the soul of the artist ascends from the earthly realm into the heavenly… And precisely at the boundary between the two worlds, the soul’s spiritual knowledge assumes the shapes of symbolic imagery [or words]: and it is these images that make permanent the work of art. Art is thus materialized dream, separated from the ordinary consciousness of waking life.” (Iconostasis, 1996, p. 44)

In the end, through fantasy and sub-creation, we are reminded of the mystery and wonder that lie at the heart of existence, a mystery Tolkien believed could ultimately lead us back to God. The Tolkien test for AI is whether it can ‘create’ genuinely original work that bears no correspondence to anything a human has ever sub-created, as an extension of the original creation act and ultimate expression of originality. To return to Pinsent’s question concerning the justification for the creative imagination in a world of pragmatic materialism, could AI ‘create’ an entire family of imaginary languages for imaginary peoples in an imaginary world? And if it could, would anyone recognize it?