by Scott Samuelson

Once I’ve hung a picture on the wall, I pretty much never look at it again. It goes right from the forefront of my mind to the background of my room. It’s only when a guest comments on it that I bother to see it again.

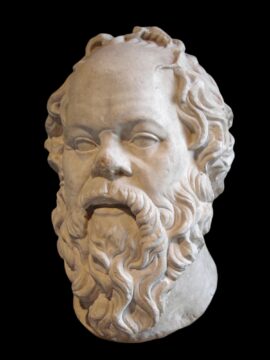

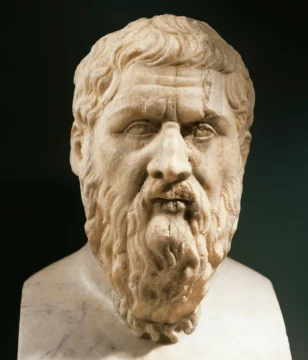

A similar thing can be said for iconic works of art. We see them so often that we don’t bother to look at them anymore. A good example is Raphael’s School of Athens, especially its central scene of Plato and Aristotle in conversation. It’s used to illustrate pretty much every article concerning philosophy in the popular media. When we see it, we think “philosophy” or maybe “classics” and move on.

Art historians aren’t much better. They love the game of guessing who each figure in the School of Athens is modeled on or is supposed to represent. Instead of seeing “philosophy,” their great advance is to see “Michelangelo” and “Heraclitus.” As fun and minorly informative as the guessing game can be, it still sees the painting as a cheap allegory.

I started taking a fresh look at the School of Athens when I had to teach it as part of a study abroad course to Rome. The more I looked at it, the more I started to see it as a compelling and comprehensive philosophy of education. To my surprise, I’ve found that it illustrates the complexity of what I aspire to as a teacher. Read more »

The recent show

The recent show

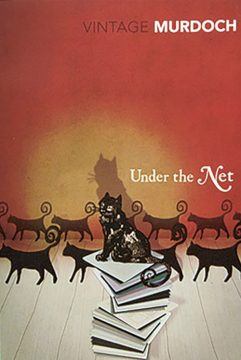

Mother’s friend departed after their weekly get-together for tea, cakes and gossip, but she forgot to take her book. It was a slim hardback with the blue and yellow banded cover of a subscription book club. It lay on the arm of the sofa for ten minutes and then, before anybody noticed, it vanished – relocated to my bedroom. I was fifteen, and this would be the first adult novel I had ever read. Its title was Under the Net by Iris Murdoch. Iris was my “first” – first adult novelist and first woman writer, and she has remained fixed in my affections over the decades. Under the Net was also Murdoch’s first novel, published in 1954. I was so naively charmed that I made a precocious promise to myself to reread it fifteen years later to see if its appeal lasted. I already knew that in the coming years I would not be rereading my previous favourites, my childhood book collections of Just William, Biggles, Billy Bunter and John Carter’s adventures on Mars. Unlike them, Under the Net had mysteries and ideas I did not yet fathom, but would need to discover.

Mother’s friend departed after their weekly get-together for tea, cakes and gossip, but she forgot to take her book. It was a slim hardback with the blue and yellow banded cover of a subscription book club. It lay on the arm of the sofa for ten minutes and then, before anybody noticed, it vanished – relocated to my bedroom. I was fifteen, and this would be the first adult novel I had ever read. Its title was Under the Net by Iris Murdoch. Iris was my “first” – first adult novelist and first woman writer, and she has remained fixed in my affections over the decades. Under the Net was also Murdoch’s first novel, published in 1954. I was so naively charmed that I made a precocious promise to myself to reread it fifteen years later to see if its appeal lasted. I already knew that in the coming years I would not be rereading my previous favourites, my childhood book collections of Just William, Biggles, Billy Bunter and John Carter’s adventures on Mars. Unlike them, Under the Net had mysteries and ideas I did not yet fathom, but would need to discover.