by Mary Hrovat

When I was growing up, my mother and I would sometimes read or recite poetry to each other. Ours was not a poetic household, and my father would occasionally complain: “If poets have something to say, why don’t they just say it?” But we thought they did say it, albeit indirectly sometimes, and we continued with our Longfellow, a bit more quietly.

When I was growing up, my mother and I would sometimes read or recite poetry to each other. Ours was not a poetic household, and my father would occasionally complain: “If poets have something to say, why don’t they just say it?” But we thought they did say it, albeit indirectly sometimes, and we continued with our Longfellow, a bit more quietly.

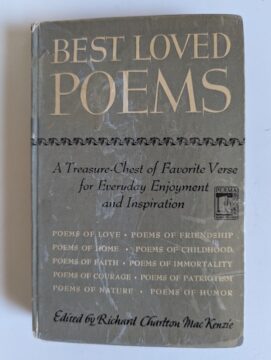

My mother had a collection of Longfellow’s works (he was probably her favorite poet). Another book we frequently read from was an anthology called Best Loved Poems: A Treasure-Chest of Favorite Verse for Everyday Enjoyment and Inspiration (edited by Richard Charlton MacKenzie, copyright 1946). Everyday enjoyment, that’s what we were after.

Mom was opposed to what she called moping, and she especially loved Longfellow’s “A Psalm of Life” (“Let us then be up and doing / With a heart for any fate”) and “The Rainy Day” (“Be still, sad heart! and cease repining; / Behind the clouds is the sun still shining.”). We also found Excelsior very satisfying to read aloud. It was one of the poems that taught me that you don’t need to understand everything about a poem to get the message or to enjoy it. I suspect this was also one of the poems my father found most annoying, because you really want to belt out the repeated word Excelsior, and perhaps raise a fist skyward as you do.

We often read other poems written in a similar spirit of inspiration—for example, “Invictus,” by William Ernest Henley and “Say Not the Struggle Naught Availeth,” by Arthur Hugh Clough. I was comforted by Clough’s words of encouragement to the doubtful and worried; even as a child I was often apprehensive. I can’t remember how I felt about “Invictus,” except that, like “Excelsior,” it was satisfying to recite with great gusto. “In the fell clutch of circumstance / I have not winced nor cried aloud,” we exclaimed. The language seems all out of proportion to the life we lived, but I liked the archaic phrasing (who talks about the fell clutch of anything these days?). Looking back, I see that my struggles became more difficult when I tried to meet them with silent, tearless stoicism. Perhaps I was trying to borrow bravado.

Mom and I also enjoyed poems of nature and home and childhood. Longfellow wrote at least three poems about night and evening. There are still moments when I’m out walking at twilight and the opening lines of “The Day Is Done” come unbidden to mind: “The day is done, and the darkness / Falls from the wings of Night, / As a feather is wafted downward / From an eagle in his flight.” We liked the gentle poems about red geraniums or the neighbor’s roses or the bright blue skies of October. We loved anything about a garden.

There was a small section of humorous poems in Best Loved Poems, including the purple cow poem. I was gleefully delighted with “The Pessimist,” by Ben King. “Nothing to do but work,” he complains, “Nothing to eat but food; Nothing to wear but clothes / To keep one from going nude.” He continues for several verses in similar vein: “Nowhere to go but out, / Nowhere to come but back.” This poem still makes me smile. (I was pleased to see, while researching this piece, that Garrison Keillor read it on The Writer’s Almanac, in 2001.)

My mother was not above finding a little unintended humor in Longfellow’s work. She would sometimes read “The Children’s Hour” with her own running commentary on what small children actually look and sound like. The poem includes the phrases “the patter of little feet” and “voices soft and sweet,” sentimental phrases that might occur most easily to a person who sees children for an hour a day rather than one who attends to their needs full-time.

We made bywords of certain lines of poetry. In fact, “Be still, sad heart! and cease repining” was one of Mom’s watchwords. We also liked to remind each other “how sublime a thing it is to suffer and be strong,” from Longfellow’s “The Light of Stars,” in which he suggests that we draw on the strength and heroism of Mars when the planet appears in the night sky. The poem also has a line about being resolute and calm “as one by one thy hopes depart.” I was young and inexperienced enough to see my efforts to find a job at 16 reflected in this line. I attended high school by correspondence course and graduated at 16; it took a while to find someone willing to hire a 16-year-old for a permanent full-time clerical job. After each disappointment, Mom would remind me to suffer and be strong, in hopes that I would soon find the suffering sublime.

We also referred to a little poem by the Persian poet Saadi about selling one of your last loaves of bread in order to buy hyacinths to feed the soul. The poem felt especially apt when I came home from our thrift shop trips with books or albums of classical music. Money was always tight, and it seemed self-indulgent to buy books, even at thrift shop prices.

I surely had access to other books of poetry, but when I had to select poems to memorize and read aloud in class in seventh or eighth grade, I chose them from Best Loved Poems: “Requiem,” by Robert Louis Stevenson, and “Sea Fever,” by John Masefield. I chose “Requiem” in part because it was short, but also because I loved the swinging rhythm and the feeling of peace and release. I can’t imagine how it looked to adults when a 13-year-old read that poem. I think my mother suggested “Sea Fever.” I’m not sure why she liked it; I think I enjoyed it in part because of the imagery of the sky, the grey dawn breaking, the windy day with white clouds flying. My affinity for the sky goes way back.

∞

Some of the poems in Best Loved Poems might be described as sentimental, but we didn’t mind. In fact, I don’t think I was capable of looking at the book critically when I was in my teens. I knew so little, and my context was so narrow. I couldn’t marvel, as I do now, that First Footsteps, a sweet little poem about a baby’s first steps, was written by Algernon Charles Swinburne. I wasn’t reminded of the song “Bread and Roses,” based on the poem of the same name by James Oppenheim, when we read about how hyacinths can feed the soul. Both poems make the point that people need beauty just as much as they need food; it’s interesting that “Bread and Roses” goes further and suggests that everyone deserves to have both. I didn’t know anything about “The Purple Cow” or its author Gelett Burgess. I couldn’t compare the book to other anthologies. (Now I delight in anthologies. Someday I’ll write an anthology-ology about the different kinds, and the pleasures of browsing anthologies compiled in the past.)

Now I can see Best Loved Poems as something like a Reader’s Digest of poetry. There was considerable moral uplift among the poems of love and inspiration and patriotism. The book was implicitly Christian and included well-known Christmas carols and hymns. Most of the poems were formal verse (rhymed and metrical). Some of the poets would be familiar, in 1946 and now, to anyone who knows anything about literature, but some are unknown or little-known today. Many of them were male, but there were a fair number of women among them. I’d guess that most of them were white. Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson are represented by a single poem apiece. Robert Frost is completely absent.

In short, Best Loved Poems was a book of its time, and of course Longfellow was a poet of his. I had to start somewhere. Poetry is a vast landscape; regardless of the route you enter by, countless paths are available once you are enchanted by the poetic use of words. Luckily, I was led to or found my way to other books of poetry as a young adult.

I was given a book of poems by Emily Dickinson as a teenager, and I found a copy of Immortal Poems of the English Language (edited by Oscar Williams, copyright 1952) at a thrift shop. I’m sure that book was used in college courses at the time, and I also had a few textbooks from my high school and college courses on literature. These books introduced me to many other poets and types of poetry, to e.e. cummings and Matthew Arnold, John Donne and Gerard Manley Hopkins, and much else besides. A college textbook, The Experience of Literature, included a few poems by Paul Simon, demonstrating to me that poetry was still being made, that I could even hear it on the radio, set to music.

Later I picked up the Norton anthologies of American and English literature. Friends and life introduced me to so many poets, including Adrienne Rich and Diane di Prima and Muriel Rukeyser. These days I follow many paths, in particular those made by the poets of nature. My reading on deep ecology in the 1990s led me to Robinson Jeffers and Gary Snyder, and from there I eventually found my way to poets such as Joy Harjo and Robert Haines, Edward Thomas and John Clare, and many others. I’m a little surprised to look back at what I read when I was a teenager and to realize how limited that banquet was, because it looked ample at the time. I love that about poetry, that there’s always more to discover.

Later I picked up the Norton anthologies of American and English literature. Friends and life introduced me to so many poets, including Adrienne Rich and Diane di Prima and Muriel Rukeyser. These days I follow many paths, in particular those made by the poets of nature. My reading on deep ecology in the 1990s led me to Robinson Jeffers and Gary Snyder, and from there I eventually found my way to poets such as Joy Harjo and Robert Haines, Edward Thomas and John Clare, and many others. I’m a little surprised to look back at what I read when I was a teenager and to realize how limited that banquet was, because it looked ample at the time. I love that about poetry, that there’s always more to discover.

I still love many of the poems that I loved when I was young, though. There are mornings when I’m reluctant to get out of bed, and I encourage myself by saying, “Up and doing! A heart for any fate.” I wish I could tell my mother how the words she shared have stayed with me.

∞

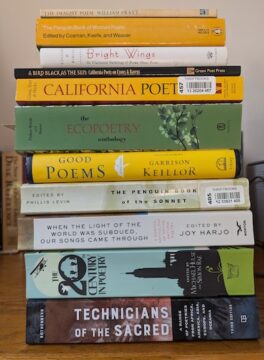

The following books appear in the stack of anthologies:

The Imagist Poem, edited by William Pratt (Dutton, 1963)

The Penguin Book of Women Poets, edited by Carol Cosman, Joan Keefe, and Kathleen Weaver (Penguin Books, 1978)

Bright Wings: An Illustrated Anthology of Poems about Birds, edited by Billy Collins, paintings by David Allen Sibley (Columbia University Press, 2009)

A Bird Black as the Sun: California Poets on Crows & Ravens, edited by Enid Osborn and Cynthia Anderson (Green Poet Press, 2011)

California Poetry: From the Gold Rush to the Present, edited by Dana Gioia, Chryss Yost, and Jack Hicks (Santa Clara University and Heyday Books, 2004)

The Ecopoetry Anthology, edited by Ann Fisher-Wirth and Laura-Gray Street (Trinity University Press, 2020)

Good Poems for Hard Times, selected and introduced by Garrison Keillor (Viking, 2005)

The Penguin Book of the Sonnet, edited by Phillis Levin (Penguin Books, 2001)

When the Light of the World Was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through: A Norton Anthology of Native Nations Poetry, edited by Joy Harjo et al. (Norton, 2020)

The 20th Century in Poetry, edited by Michael Hulse and Simon Rae (Pegasus Books, 2011)

Technicians of the Sacred: A Range of Poetries from Africa, America, Asia, Europe, and Oceania (3rd ed.), edited with commentaries by Jerome Rothenberg (University of California Press, 2017)

(I could make another stack, at least as tall and just as varied, with other anthologies, and that’s just books I own.)

∞

You can find more of my work at MaryHrovat.com.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.