by Jochen Szangolies

We have entered a versioned world. A new release of a major AI model (GPT-5) triggers the subsequent release of new versions of articles variously hyping and disparaging the progress it represents. How does it stack up in benchmarks against earlier models? How well can it code? Can you feel the AGI (even more)? Will this take my job, or skip that step and directly declare war on its creators?

We are reminded, in each iteration of the cycle, of both the promises and perils of ongoing AI developments. For every article touting a supposed productivity increase, there is one warning against mass unemployment. Every voice decrying the still-unsolved fundamental problems of generative AI is matched by one breathlessly updating their priors for imminent human-equivalent AGI (or alternatively, increasing their ‘P(doom)’, the estimated likelihood that AI will kill us all). In their predictably incremental nature, they mirror the releases they chronicle: the miracle of AI progress is beginning to grow stale.

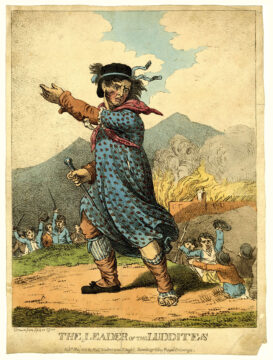

This article is itself, in parts at least, an iteration of an earlier one. My excuse for writing it is that I think the concerns raised there, of how AI threatens to diminish the meaning of human creativity, is still not quite appreciated in the right way. Mass production, copyright infringement, oversaturation: these are real issues, but fail to get to the heart of it. Read more »