by Derek Neal

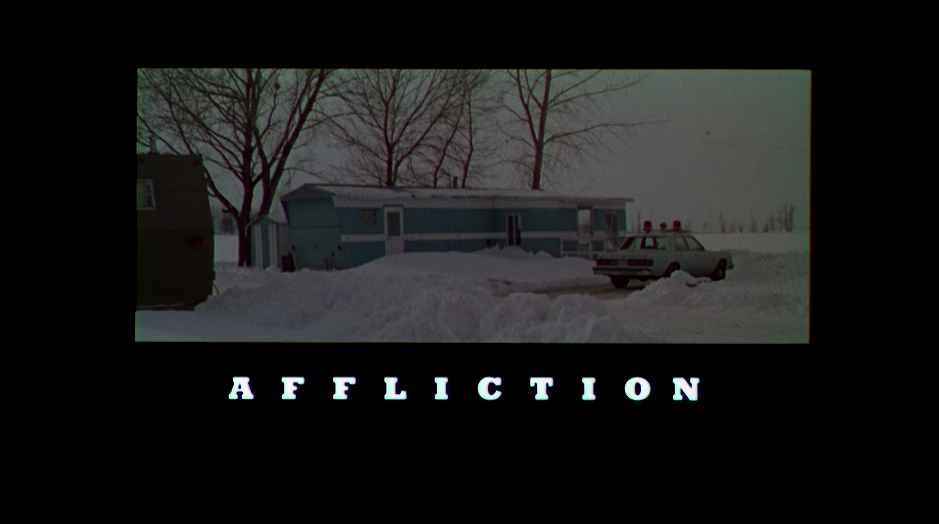

The opening credits of Affliction (1997) feature small, rectangular images that fill only half the screen. You wonder if something is wrong with the aspect ratio, or if the settings have been changed on your television. A succession of images is placed before the viewer: a farmhouse in a snowy field, a trailer with a police cruiser parked in front, the main street of a small, sleepy town, the schoolhouse, the town hall. The last image is a dark, rural road, with a mountain in the distance. Finally the edges of the image expand, fill the screen, and a voice begins to narrate:

The opening credits of Affliction (1997) feature small, rectangular images that fill only half the screen. You wonder if something is wrong with the aspect ratio, or if the settings have been changed on your television. A succession of images is placed before the viewer: a farmhouse in a snowy field, a trailer with a police cruiser parked in front, the main street of a small, sleepy town, the schoolhouse, the town hall. The last image is a dark, rural road, with a mountain in the distance. Finally the edges of the image expand, fill the screen, and a voice begins to narrate:

This is the story of my older brother’s strange criminal behavior and disappearance. We who loved him no longer speak of Wade. It’s as if he never existed. By telling his story like this, by breaking the silence about him, I tell my own story as well. Everything of importance, that is, everything that gives rise to the telling of this story occurred during a single deer hunting season in a small town in upstate New Hampshire where Wade was raised, and so was I. One night, something changed and my relation to Wade’s story was different from what it had been since childhood. I marked this change by Wade’s tone of voice during a phone call two nights after Halloween. Something I had not heard before. Let us imagine that around eight o’clock on Halloween Eve…

Then the narrator’s voice disappears, and we are in the car with Wade, played by Nick Nolte, and his daughter. We are in the story, we are ready to be swept away, or in the case of this movie, submerged into the depths, but we have been prepared in such a way—starting from outside the story, outside the narrative—that we are aware of the artificiality of what we are seeing. Affliction tells us that it is a movie. The small images, which look like postcards, are presented to us as miniature models of different sets. The farmhouse becomes “THE HOUSE.” The main street becomes “MAIN STREET.” While they will take on specific characteristics within the movie, we know from the prologue that they are eternal, and we will be reminded of this at the end as well.

The voiceover achieves a similar effect. The narrator, played by Willem Defoe, removes tension and drama from the plot by spoiling the ending: Wade becomes a criminal and disappears. He does not even attempt to convince us that the story is real, that it actually happened, because he says, “Let us imagine.” Is this not bad storytelling? It may be appropriate for a children’s story, a fairy tale, but for a mature film like Affliction, a film dealing with murder, paranoia, and male violence? Shouldn’t a story like this try to convince its audience that it’s real, by building up a wealth of detail and creating realistic, lifelike characters? Perhaps a certain type of story, but not this one. Nick Nolte has a name in Affliction, but his real name is “THE SON.” Willem Defoe is “THE BROTHER.” James Coburn, without a doubt, is “THE FATHER.” Affliction is in the land of myth.

At the end of the movie, the narrator tells us the conclusion to the story in voiceover. The images on the screen are, first, Wade drinking at a table as a barn burns in the background, and then, a murder committed in a snowy forest:

The historical facts are known by everyone—all of Lawford, all of New Hampshire, some of Massachusetts. Facts do not make history. Our stories, Wade’s and mine, describe the lives of boys and men for thousands of years, boys who were beaten by their fathers, whose capacity for love and trust was crippled almost at birth and whose best hope, if any, for connection with other human beings lay in an elegiac detachment, as if life were over.

It’s how we keep from destroying in turn our own children and terrorizing the women who have the misfortune to love us, how we absent ourselves from the tradition of male violence, how we decline the seduction of revenge.

There will be no more mention of him [Wade], or his friend Jack Hewitt, or our father. The story will be over. Except that I continue.

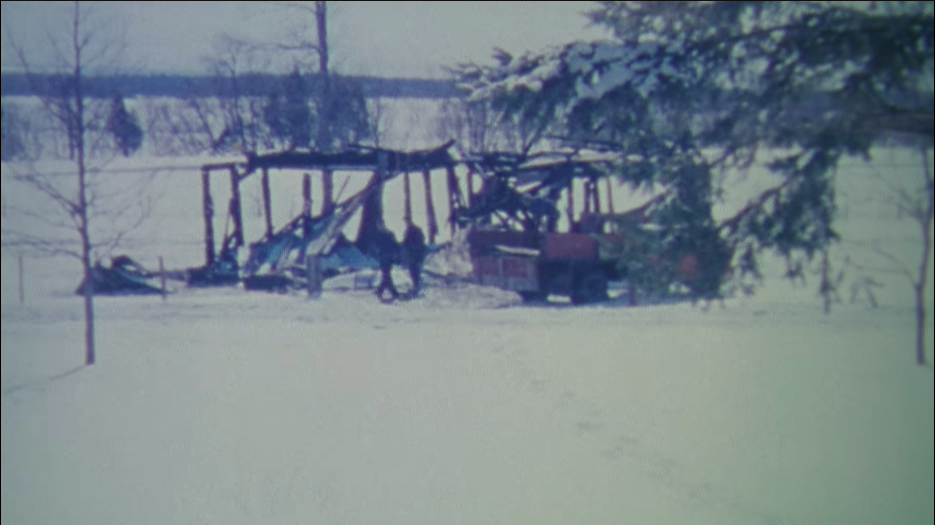

As Willem Defoe comes to the end of his narration, the camera moves through their old family home before looking out the window and settling on a few workmen tearing down the remains of the burned barn. We watch these men, who have never appeared in the story before, for close to 30 seconds, a rather long shot, especially considering their unimportance to the plot of the film. Yet we feel as if we could watch these men for eternity. The screen fades to black and the credits roll. What is happening in this final shot? Why does the film depart from the characters we’ve followed for close to two hours and leave us with complete strangers? In one sense, it is the reverse of the opening shot. Just as we started from outside the film before entering into it, at the end we leave the characters of the film and are reminded that there is a world outside of the one we’ve been following. A strange paradox is achieved: just as the story of Wade, his brother, and his father is a timeless one, a story that “describe[s] the lives of boys and men for thousands of years,” it is also one story among many, and we feel that while we’ve visited them for a few hours, we could have visited another family, different yet the same. The workmen have their stories, too.

As Willem Defoe comes to the end of his narration, the camera moves through their old family home before looking out the window and settling on a few workmen tearing down the remains of the burned barn. We watch these men, who have never appeared in the story before, for close to 30 seconds, a rather long shot, especially considering their unimportance to the plot of the film. Yet we feel as if we could watch these men for eternity. The screen fades to black and the credits roll. What is happening in this final shot? Why does the film depart from the characters we’ve followed for close to two hours and leave us with complete strangers? In one sense, it is the reverse of the opening shot. Just as we started from outside the film before entering into it, at the end we leave the characters of the film and are reminded that there is a world outside of the one we’ve been following. A strange paradox is achieved: just as the story of Wade, his brother, and his father is a timeless one, a story that “describe[s] the lives of boys and men for thousands of years,” it is also one story among many, and we feel that while we’ve visited them for a few hours, we could have visited another family, different yet the same. The workmen have their stories, too.

Another film that achieves this effect is Badlands (1973), the debut movie of Terrence Malick. The story begins with voiceover narration, just as in Affliction, only this time we hear from the character on screen rather than off. Holly, played by a young Sissy Spacek, sits on her bed while her disembodied voice tells us:

My mother died of pneumonia when I was just a kid. My father had kept their wedding cake in the freezer for ten whole years. After the funeral he gave it to the yardman…He tried to act cheerful, but he could never be consoled by the little stranger [Spacek] he found in his house. Then, one day, hoping to begin a new life away from the scene of all his memories, he moved us from Texas to Ft. Dupree, South Dakota.

Just as with Defoe’s “Let us imagine…,” we have another instance of a sort of fairytale language in, “One day, hoping to begin a new life…” Again we are reminded that we are in a story. A few images of Ft. Dupree, South Dakota are presented before us: a back alley lined with trash cans, a sleepy residential street, then another street. Slowly a garbage truck rolls into view with our hero, Kit (played by Martin Sheen), who will run away with Holly, the narrator. While not as extreme as Affliction in its presentation of setting, Badlands still shows us a succession of images without people at the beginning of the film, creating the effect of an empty stage that will then be populated.

Just as with Defoe’s “Let us imagine…,” we have another instance of a sort of fairytale language in, “One day, hoping to begin a new life…” Again we are reminded that we are in a story. A few images of Ft. Dupree, South Dakota are presented before us: a back alley lined with trash cans, a sleepy residential street, then another street. Slowly a garbage truck rolls into view with our hero, Kit (played by Martin Sheen), who will run away with Holly, the narrator. While not as extreme as Affliction in its presentation of setting, Badlands still shows us a succession of images without people at the beginning of the film, creating the effect of an empty stage that will then be populated.

The camera returns to Holly, twirling a baton (immortalized in Bruce Springsteen’s “Nebraska”), and we hear more of her voiceover narration:

Little did I realize that what began in the alleys and back ways of this quiet town would end in the Badlands of Montana.

As in Affliction, the ending is revealed at the beginning. This story will “end” in the Badlands, and it certainly will not be a happy one: Kit and Holly are apprehended by the police after killing numerous people as they make their way across the country. Yet for all the bodies left in their wake, the film is not dark in the same way that Affliction is. Kit, despite murdering multiple people, is not evil; he’s affable and charismatic, likeable, even, and not in a manipulative, seductive way, but in a pure, innocent way. This is what makes writing about the film so difficult, as a synopsis of the plot presents a distorted view of the mood and feeling of the film.

Badlands is not a portrait of reality, but a fable told through the eyes of a 15-year-old girl. Paradoxically, in mediating the events of the film in this way, in aestheticizing them, it is able to tell us something deeper and truer about life than had it tried to present something in a naturalistic, realistic way. Kit and Holly are tragic, sympathetic figures, who have both filled the meaninglessness of their lives with fantasies that can’t survive in the real world—Kit modelling himself on James Dean, Holly on the clichés of romance stories à la Madame Bovary. The events of the story are framed through Holly’s narration, giving them a dreamlike quality. Here is how Holly describes things:

Little by little we fell in love.

Our time with each other was limited and each lived for the precious hours when he or she could be with the other away from all the cares of the world.

He wanted to die with me, and I dreamed of being lost forever in his arms.

Something must’ve told him that we’d never live these days of happiness again, that they were gone forever.

At the end of Badlands, after Kit and Holly have been apprehended, the film invites us to imagine other characters outside the story, just as in Affliction. In a documentary on the making of the film, associate editor Billy Weber explains:

In all three of his [Malick’s] movies he’ll do cuts to people that you don’t have any idea who they are, and it’s just to show you that, it’s this sense of life continuing on. Towards the very end of the movie, Martin and Sissy have been taken away in a plane, the plane hasn’t taken off yet, but it has taxied away from where it was on the tarmac, and we cut to a mailman carrying a sack of mail, and the point of that shot was to show you someone that in the midst of this chaos, or tragedy, that life is going on in other places, and that this guy carrying this sack of mail has no idea that there is this wanted killer on this plane that he’s walking past.

This mailman is not a random choice, but a person who reminds us of Kit at the beginning of the film. He’s in uniform, just as Kit was in his garbageman’s uniform; he’s carrying two large sacks, just as Kit carried bags of garbage. They are both manual laborers working menial jobs. He is a young man who resembles Kit, and we recall that Kit set off with Holly after losing his job, then getting a job he couldn’t stand “working cattle over at the pens” and subsequently quitting. We don’t blame Kit for these choices as we watch the film, we understand him, and we understand too that a man losing his job, his purpose, is a dangerous thing and a typical beginning to an eternal story. Is the mailman capable of doing what Kit did, if events were to unfold in a certain way? We feel that he is.

This mailman is not a random choice, but a person who reminds us of Kit at the beginning of the film. He’s in uniform, just as Kit was in his garbageman’s uniform; he’s carrying two large sacks, just as Kit carried bags of garbage. They are both manual laborers working menial jobs. He is a young man who resembles Kit, and we recall that Kit set off with Holly after losing his job, then getting a job he couldn’t stand “working cattle over at the pens” and subsequently quitting. We don’t blame Kit for these choices as we watch the film, we understand him, and we understand too that a man losing his job, his purpose, is a dangerous thing and a typical beginning to an eternal story. Is the mailman capable of doing what Kit did, if events were to unfold in a certain way? We feel that he is.

The endings of Affliction and Badlands, while reminding us of other characters and possibilities, still maintain a relatively coherent narrative structure; they feature moments of experimentation, but we would not call them experimental films. This is in contrast to L’Eclisse (1962), directed by Michelangelo Antonioni, which features a remarkable eight-minute ending sequence in which we expect the main characters to appear, but they never do. Instead, other people are captured by the camera in the neighbourhood where Piero (played by Alain Delon) and Vittoria (played by Monica Vitti) have met throughout the film. The neighbourhood itself, while in Rome, is not at all what one might expect; rather than shots of the Coliseum or cobblestone streets, there are sterile apartment blocks, wide, perfectly paved streets, and isolated individuals. We see that a new world is in the process of being constructed, but one that seems indifferent to the people who populate it. Antonioni’s camera alternates between this new world, identified by the perfect right angles of an apartment balcony, the line of uniform streetlights, and the natural world that must be brought under human control, but which threatens to break free: ants crawling on tree bark, water trickling through the detritus of building construction. Clouds cover the sun, but a streetlight illuminates to replace it. A man gets off a bus with a newspaper: the front page says, “THE ATOMIC RACE” while the inside says, “PEACE IS FRAGILE.” The inhabitants of this zone, for the most part, do not interact.

The endings of Affliction and Badlands, while reminding us of other characters and possibilities, still maintain a relatively coherent narrative structure; they feature moments of experimentation, but we would not call them experimental films. This is in contrast to L’Eclisse (1962), directed by Michelangelo Antonioni, which features a remarkable eight-minute ending sequence in which we expect the main characters to appear, but they never do. Instead, other people are captured by the camera in the neighbourhood where Piero (played by Alain Delon) and Vittoria (played by Monica Vitti) have met throughout the film. The neighbourhood itself, while in Rome, is not at all what one might expect; rather than shots of the Coliseum or cobblestone streets, there are sterile apartment blocks, wide, perfectly paved streets, and isolated individuals. We see that a new world is in the process of being constructed, but one that seems indifferent to the people who populate it. Antonioni’s camera alternates between this new world, identified by the perfect right angles of an apartment balcony, the line of uniform streetlights, and the natural world that must be brought under human control, but which threatens to break free: ants crawling on tree bark, water trickling through the detritus of building construction. Clouds cover the sun, but a streetlight illuminates to replace it. A man gets off a bus with a newspaper: the front page says, “THE ATOMIC RACE” while the inside says, “PEACE IS FRAGILE.” The inhabitants of this zone, for the most part, do not interact.

Immediately preceding this scene, Piero and Vittoria plan their meeting that will never happen:

Immediately preceding this scene, Piero and Vittoria plan their meeting that will never happen:

Piero: We’ll see each other tomorrow?

Vittoria: (Nods yes)

Piero: We’ll see each other tomorrow, and the day after…

Vittoria: And the next day again…

Piero: And the one after…

Vittoria: And this evening.

Piero: At eight o’clock…The usual spot.

Vittoria leaves into the anonymity of city streets while Piero returns to his desk to continue his work as a stockbroker. They both seem overwhelmed, unsure of why they are where they are, as if they’ve chosen their lives by pure chance, and the feeling one has watching them is a deep sense of existential alienation. When we then see the anonymous characters at the end of the film, the effect is the same as in Affliction and Badlands: we realize that Piero and Vittoria’s story is not the subject of the film, the film is not about them but has instead chosen them from a crowd of people, any of these other characters could have been the focus of the film, and it would have been the same film, because the story is a universal one. The subject this time is alienation in the face of modernity, which we see written on every person’s face in the final sequence, who, by the way, are not actors but the real inhabitants of this Roman neighbourhood called “EUR,” a centrally planned district originally intended to serve as a celebration of fascism. In his commentary on the film, critic Seymour Chatman summarizes the ending: “It is a whole society, ultimately a whole civilization, that cannot meet.”

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.