I have been thinking about artificial intelligence and its implications for most of my adult life. In the mid-1970s I conducted research in computational semantics which I used in analyzing Shakespeare’s famous Sonnet 129, “Th’ Expense of Spirit.” In the summer of 1981 I participated in a NASA study investigating ways to incorporate AI in NASA operations and missions. There I learned about an earlier NASA study that had looked into creating self-replicating factories on the moon.

I have been thinking about artificial intelligence and its implications for most of my adult life. In the mid-1970s I conducted research in computational semantics which I used in analyzing Shakespeare’s famous Sonnet 129, “Th’ Expense of Spirit.” In the summer of 1981 I participated in a NASA study investigating ways to incorporate AI in NASA operations and missions. There I learned about an earlier NASA study that had looked into creating self-replicating factories on the moon.

“Wow,” thought I to myself, “does that mean potentially infinite ROI?” How so? “Well, it’s going to cost a lot to develop the initial equipment drop and transport it to the moon, but once that’s been done, and those self-replicating factories and amortized the initial investment, it’s all profit from that point on.” That is, since the factories can replicate themselves without further investment from earth, we can reap the profits from whatever it is that these factories produce, other than more factories.

Now, whether or not that’s actually possible, that’s another question. But it was an interesting fantasy. That’s how AI is, it breeds giddy fantasies in those who catch the bug.

Somewhat later, and in a more sober mood, David Hays and I argued, “Sooner or later we will create a technology capable of doing what, heretofore, only we could.” We also pointed out that “We still do, and forever will, put souls into things we cannot understand, and project onto them our own hostility and sexuality, and so forth.”

There’s plenty of that going around these days. There’s a raft of AI hype that’s been floating around since ChatGPT’s release in late November of 2022. One prominent strain is telling us that we are doomed to be eradicated by an over-ambitious AI. I’m quite sure that that is projective fantasy.

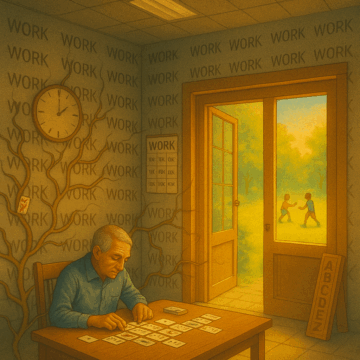

Alas, the threat of massive economic displacement seems far more real to me, and more worrying. Jobs will be lost to AI – it’s already happening, no? – and, while new jobs will be created, it does seem to me that in the long run, job loss will inevitably outpace job creation. That should be a good thing, no? To live among material abundance without the drudgery of soul-destroying work, isn’t that something to be welcomed? In the long run, yes, but in the short and mid-term, no, it is not. We are not ready. We have become addicted to work, at least in the advanced world, and will have trouble adjusting to life without it.

That’s my topic for this column. Read more »

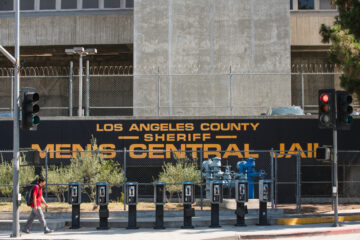

At about 6:30 am, we pulled up to the Labor Ready office in the Central District. My friend – who for the sake of this column will be called Rick – and I were responding to a trespassing call: a woman who was asked to leave the day-labor agency office was refusing.

At about 6:30 am, we pulled up to the Labor Ready office in the Central District. My friend – who for the sake of this column will be called Rick – and I were responding to a trespassing call: a woman who was asked to leave the day-labor agency office was refusing.

Donald Trump is a con man. He was that for a very long time before he entered politics. Because he is a con man, it is tempting for critics to describe his presidential victories as successful cons. However, I think that interpretation does not hold up. Because while Trump at his essence may be little more than a sociopathic con man lacking a sophisticated and flexible inferiority, voters and citizens are not simply “marks.” The electorate, especially one as large as the United States’ (over 73 million registered voters), is maddeningly complex. It reflects a stunning amount of views, ideals, fears, and nuance. And the catch is that while the elected government can never hope to fully reflect this complexity, it can unduly influence it.

Donald Trump is a con man. He was that for a very long time before he entered politics. Because he is a con man, it is tempting for critics to describe his presidential victories as successful cons. However, I think that interpretation does not hold up. Because while Trump at his essence may be little more than a sociopathic con man lacking a sophisticated and flexible inferiority, voters and citizens are not simply “marks.” The electorate, especially one as large as the United States’ (over 73 million registered voters), is maddeningly complex. It reflects a stunning amount of views, ideals, fears, and nuance. And the catch is that while the elected government can never hope to fully reflect this complexity, it can unduly influence it.

In February, after a month-long consideration, I set my New Year’s resolutions into a five-by-five grid. I made a BINGO card—twenty-four resolutions plus the FREE space. It was my attempt to gamify the whole tired resolution process that I’ve failed at so well. Surprisingly the trick seems to have worked, at least partially.

In February, after a month-long consideration, I set my New Year’s resolutions into a five-by-five grid. I made a BINGO card—twenty-four resolutions plus the FREE space. It was my attempt to gamify the whole tired resolution process that I’ve failed at so well. Surprisingly the trick seems to have worked, at least partially.

In the context of growing concern about educational equity, the persistent racial disparities associated with the Specialized High School Admissions Test in New York City continue to spark debate. As cities and school systems nationwide reconsider the role of standardized testing, the story of the origins of this test shed light on how deeply embedded policies can appear neutral while, in reality, reinforcing inequality.

In the context of growing concern about educational equity, the persistent racial disparities associated with the Specialized High School Admissions Test in New York City continue to spark debate. As cities and school systems nationwide reconsider the role of standardized testing, the story of the origins of this test shed light on how deeply embedded policies can appear neutral while, in reality, reinforcing inequality.

Nirmal Raja. Entangled / The Weight of Our Past, 2022.

Nirmal Raja. Entangled / The Weight of Our Past, 2022.

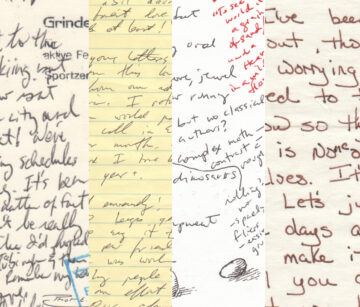

Words, so many words. Words that inspire “Ask Not,” and those that call upon our resolve “[A] date that will live in infamy.” Words that warn about the future “[W]e must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex,” and those that express optimism about it “I’ve been to the mountaintop.” Words that deny their own importance “[T]he world will little note nor long remember what we say here,” while elevating themselves and the dead they honor to immortality.

Words, so many words. Words that inspire “Ask Not,” and those that call upon our resolve “[A] date that will live in infamy.” Words that warn about the future “[W]e must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex,” and those that express optimism about it “I’ve been to the mountaintop.” Words that deny their own importance “[T]he world will little note nor long remember what we say here,” while elevating themselves and the dead they honor to immortality.

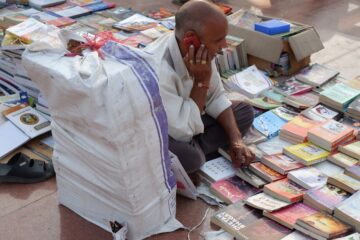

Dhingra’s book is built on many months of Sundays spent walking the market, talking to traders and readers, and mapping the bazaar’s assemblages and syncopations. I was lucky enough to tag along on one of these expeditions in July 2023. Arriving empty-handed, we traced a circuitous route between tables piled high with dog-eared paperbacks under billowing canopies. I departed clutching lucky finds: a 1950s Urdu story collection and a strange out-of-print children’s novel called

Dhingra’s book is built on many months of Sundays spent walking the market, talking to traders and readers, and mapping the bazaar’s assemblages and syncopations. I was lucky enough to tag along on one of these expeditions in July 2023. Arriving empty-handed, we traced a circuitous route between tables piled high with dog-eared paperbacks under billowing canopies. I departed clutching lucky finds: a 1950s Urdu story collection and a strange out-of-print children’s novel called