by Jerry Cayford

I was always attracted to that old dichotomy: people must be either stupid or lying when they claim to believe some obvious falsehood. This dichotomy is a staple of Democratic theorizing about our political culture. (Sometimes the choice is between stupid and evil, which amounts to the same.) For example, Adam-Troy Castro’s social media classic “Why Do Liberals Think Trump Supporters Are Stupid?” has been circulating since halfway through Trump’s first term. But this simple dichotomy is losing its appeal. It is just not plausible that tens of millions of ordinary Republicans—our neighbors, friends, and families—are stupid or evil. There have been many proposed explanations of this puzzle: information siloes hide the obvious from otherwise intelligent people; tribalism exerts a powerful evolutionary draw. I believe, though, that there is a different and hidden complexity here.

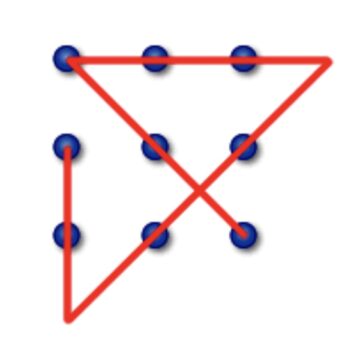

I use the word “complexity” deliberately, because my argument draws on one of the icons of chaos theory (aka complexity theory) known as the “Coastline Paradox.” That name refers to a 1967 paper, “How Long Is the Coast of Britain?” by one of the pioneers of chaos theory, Benoit Mandelbrot. James Gleick provides a quick introduction to the topic in “The Man Who Reshaped Geometry” (1985), and a thorough treatment in his book Chaos: Making a New Science (1987). But the Coastline Paradox itself is easy to understand.

Imagine you measure the coast of Britain by putting markers every ten miles and summing the distances between them. You get a certain result. If you put markers every mile, you get a larger result. Measure the coast with a yardstick: longer still. With an inch ruler: longer. The coast will continue to get longer as you trace it around ever-smaller irregularities, around every grain of sand. So, how long is the coast? As Gleick says in his article, “In fact, it depends on the length of your ruler. As the scale becomes finer and finer, bays and peninsulas reveal new subbays and subpeninsulas, and the length—truly—increases without limit, at least down to atomic scales.” In a sense, physical length does not exist. Or, physical lengths are all infinite. Or, better, length depends on your method of measuring.

Examining length gives us a glimpse into a new picture of how the things we say and believe relate to reality. Read more »

![Henri Matisse created many paintings titled 'The Conversation'. This, from 2012, is of the artist with his wife, Amélie. [Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia].](https://3quarksdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Matisse_Conversation-360x292.jpg)