by Chris Horner

What does it mean to live a Good Life in the secular west? Good can mean more than one thing, of course: apart from moral good – doing the right or ‘good’ thing, there is the idea of ‘good’ as flourishing, being happy, fulfilled. The latter matters to us a lot, judging by all the self-help books, YouTube influencers, Rules for Life and so on. For very many lucky enough not to have to worry about poverty or war there still seems a grinding anxiety about how to achieve a happy life. That life seems to be Elsewhere. But why? Some would argue that the angst is due a loss of a shared way of life, one grounded in a conception of human purpose. So, we get nihilism and sense of anomie. Yet lost wallets are returned, and courtesy is still exhibited in everyday situations. If this is moral anarchy, it is not as chaotic as one might expect. Nevertheless. I think something has changed for moderns.

With the decline of an Authority often associated with the Christian church in the West, many people experience the question of what one should do as a burden. As an unlamented Paternal Authority wanes, anxiety about happiness and fulfilment takes its place. The new Superego command is to enjoy oneself, be the best one can be, stay fit, be loved, and be attractive. Consequently, we turn to an army of experts and coaches eager to provide us with ‘rules for living’. And the appetite for moral judgment hasn’t left us either: yet more rules about what one ought to say or not say (rather than action that might change anything).

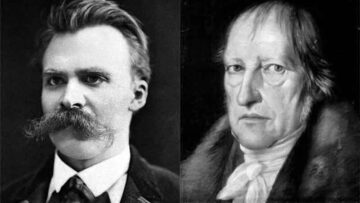

Modernity—however we define it—follows the Enlightenment. Kant described Enlightenment as the end of tutelage and the accession to maturity, with the responsibilities that come with freedom. Freedom is understood as the end of the tyranny of princes and prelates, the chance to fulfil one’s desires. However, greater knowledge of the self leads to greater doubts about those desires, and the causes of Desire itself. The autonomy promised by Enlightenment seems compromised from the start. While Nietzsche, along with Freud, is regularly cited as the key figure in this creeping sense that the subject isn’t master in their own house, Hegel foreshadows both. For Hegel, too, there are no simple, undivided identities: we are divided subjects.

When we think of the impact on modern conceptions of the good life, Nietzsche comes to mind, especially his account of the ‘Death of God’, the extinction of the symbolic guarantor of meaning which is both liberating and profoundly disorienting, as described in The Gay Science. Famously, he also launches an attack on conventional morality – the binaries of good and evil. Yet Hegel, too, should be in view when we consider modern conceptions of the Good. Hegel with Nietzsche. They often diverge, but where they echo each other, we do well to notice, for it is there that a conception and a critique of modernity develops. And their differences are also instructive, for while philosophers don’t make things happen, philosophy can be, as Hegel calls it, the ‘age comprehended in thought’

When we think of the impact on modern conceptions of the good life, Nietzsche comes to mind, especially his account of the ‘Death of God’, the extinction of the symbolic guarantor of meaning which is both liberating and profoundly disorienting, as described in The Gay Science. Famously, he also launches an attack on conventional morality – the binaries of good and evil. Yet Hegel, too, should be in view when we consider modern conceptions of the Good. Hegel with Nietzsche. They often diverge, but where they echo each other, we do well to notice, for it is there that a conception and a critique of modernity develops. And their differences are also instructive, for while philosophers don’t make things happen, philosophy can be, as Hegel calls it, the ‘age comprehended in thought’

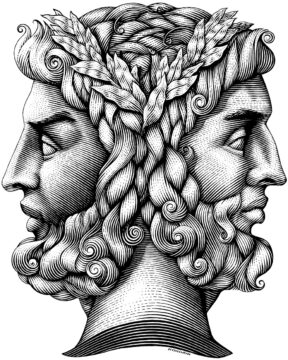

The ‘Death of God’ appears first not in Nietzsche, but in in Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit (1807) to describe not the end of meaning and morality, but rather the sublation of a certain idea of the Divine in modern consciousness, away from a God of Otherness to a grasp that what religion had taught could now be understood in new terms: God was dead, yes, but the spirit of the divine now resided in human beings and their projects. For Hegel, the divine had become internalised: ‘substance becomes subject’. What would now be central was the human struggle for freedom in history.

Both philosophers rejected the idea of timeless, universal moral principles and viewed morality as an historical process, evolving through different stages of human development. Both criticised Kant’s abstract, formal approach to ethics, finding his categorical imperative too removed from concrete experience and social context. Hegel indicts those who adopt the ‘moral world view’ with a tendency to play a double game, a lack of seriousness and a kind of resentment towards anyone happy or lucky who don’t look morally deserving. Here morality at worst deflates into something small and nasty – the moralism of the hypocrite. This is very the kind of thing we find in Nietzsche too, who is powerful in his indictment of what he calls ressentiment – the life-denying, chronic psychological condition of envy, masking its grudge against the joy of others with the the long white dress of moral superiority.

Nietzsche advocated the creation of new values beyond good and evil, stressing the role of exceptional individuals acting beyond conventional morality. Hegel in contrast emphasised the importance of social institutions (family, civil society, and state) for ethical life. For Hegel, ethical life emerges through social institutions and is embedded in the practices of everyday life. This does not mean that those institutions and practices somehow achieve a peaceful synthesis that transcends contradiction and conflict: far from it. For Hegel, contradiction is never finally overcome. Hegel and Nietzsche both see that good and the evil cannot be neatly separated into different boxes. Many of Hegel’s examples in the Phenomenology of Spirit are of people who believe themselves to be good, or virtuous – and whose sense of personal rectitude and virtue is itself a kind of dangerous denial. The frenzy of the moral fanatic, the Jacobin with the guillotine of Revolutionary Virtue, the purity of the ‘Beautiful Soul’, the Hard-Hearted Judge and more. Hegel sees an evil in the Good that thinks of itself as only good.

Nietzsche advocated the creation of new values beyond good and evil, stressing the role of exceptional individuals acting beyond conventional morality. Hegel in contrast emphasised the importance of social institutions (family, civil society, and state) for ethical life. For Hegel, ethical life emerges through social institutions and is embedded in the practices of everyday life. This does not mean that those institutions and practices somehow achieve a peaceful synthesis that transcends contradiction and conflict: far from it. For Hegel, contradiction is never finally overcome. Hegel and Nietzsche both see that good and the evil cannot be neatly separated into different boxes. Many of Hegel’s examples in the Phenomenology of Spirit are of people who believe themselves to be good, or virtuous – and whose sense of personal rectitude and virtue is itself a kind of dangerous denial. The frenzy of the moral fanatic, the Jacobin with the guillotine of Revolutionary Virtue, the purity of the ‘Beautiful Soul’, the Hard-Hearted Judge and more. Hegel sees an evil in the Good that thinks of itself as only good.

Hegel’s account of the painful development of human self-consciousness, religion and morality in his account of the ‘unhappy consciousness’ in the Phenomenology has much in it to remind us of Nietzsche’s essays in the ‘Genealogy of Morality’. For both, where we are now in our conceptions of self and others is the product of a long period of change and transformation. For Nietzsche this is genealogy: the story doesn’t imply progress to any kind of goal; for Hegel there is a sense that we have moved through certain conceptions of ourselves to a point in modernity that offers us real opportunity to make freedom real in ways it has not been before.

Nietzsche’s emphasis on individual authenticity—his call to “become who you are”—has been enormously influential. The modern notion of living “authentically” owes something to his vision of individuals creating their own values rather than merely inheriting them. But Hegel reminds us that we are not just individuals making up and performing a personal moral code. If we think we can do this, we go wrong.

Nietzsche’s emphasis on individual authenticity—his call to “become who you are”—has been enormously influential. The modern notion of living “authentically” owes something to his vision of individuals creating their own values rather than merely inheriting them. But Hegel reminds us that we are not just individuals making up and performing a personal moral code. If we think we can do this, we go wrong.

Hegel’s account of the frenzy of individual, conscience-centred or pleasure-centred philosophies, and his critique both Kantian moralist and ‘beautiful soul’ excoriates the notion that morality can just be imposed by a subject onto the world. In some ways, the moral world view as represented by Kantian morality is an advance, a great statement of how the ethical subject, by giving themselves the law, can be free, but also a late version of a tradition that began with the Stoics. For them, the chaotic world, along with its uncertainties and variables, contrasts with the moral subject, who is obligated to will the Good, no matter what. But this subject either wills that which it cannot bring about, and consoles itself with its good will, or narrates a self-serving account about what it has really done. In the end, it either withdraws into its private virtue as a beautiful soul, or compromises with reality and plays a double game – posing as morally upright while taking shortcuts to get what it wants.

Hegel’s account of the frenzy of individual, conscience-centred or pleasure-centred philosophies, and his critique both Kantian moralist and ‘beautiful soul’ excoriates the notion that morality can just be imposed by a subject onto the world. In some ways, the moral world view as represented by Kantian morality is an advance, a great statement of how the ethical subject, by giving themselves the law, can be free, but also a late version of a tradition that began with the Stoics. For them, the chaotic world, along with its uncertainties and variables, contrasts with the moral subject, who is obligated to will the Good, no matter what. But this subject either wills that which it cannot bring about, and consoles itself with its good will, or narrates a self-serving account about what it has really done. In the end, it either withdraws into its private virtue as a beautiful soul, or compromises with reality and plays a double game – posing as morally upright while taking shortcuts to get what it wants.

For Hegel neither the isolated moral subject, nor the traditional societies of the past can be enough for moderns. He wants to bring together the ‘I’ of the moral subject and the ‘we’ of the community, as it is in history, with all its contradictions and conflicts –the ethical world of today. Expressions of moral principle are parasitic on the practices of an already existing society, the place of ethical substance, Sittlichkeit. So moral commandments about stealing, for instance, can only be understood in a society that already has property. Who we are and what we do can only be understood in this way. One way to grasp this is through what Hegel has to say about what an action is.

For Hegel, the full meaning of an action cannot be determined solely by the agent’s intentions. Rather, it emerges through the deed’s actual consequences, which often differ from the intended outcome, how others recognise and interpret the action, and how the action’s significance evolves over time. This retrospective dimension of action reveals meaning after the fact, rather than being fully present in the initial intention.

This undermines subjective ethics based solely on intention. If an action’s meaning emerges through public recognition, then ethics cannot be purely individual; ethical life is fundamentally social rather than merely personal. Subjective certainty is insufficient without public recognition. True freedom isn’t just making choices based on subjective intentions but acting in ways that can be recognised as meaningful within shared social contexts. When my actions are recognised by others as embodying rational principles, I achieve concrete freedom.

Hegel’s insight that ethical meaning emerges retrospectively and publicly helps us navigate these complexities rather than retreating to purely subjective ethics or rigid universal principles divorced from context. By understanding that ethical life requires this ongoing process of action, recognition, and retrospective meaning-making, we can develop ethical approaches better suited to our complex social reality.

Hegel’s insight that ethical meaning emerges retrospectively and publicly helps us navigate these complexities rather than retreating to purely subjective ethics or rigid universal principles divorced from context. By understanding that ethical life requires this ongoing process of action, recognition, and retrospective meaning-making, we can develop ethical approaches better suited to our complex social reality.

For Hegel, true freedom is realised through participation in rational social institutions. We become free not by escaping social bonds but by finding ourselves within them. Here morality is nested inside an ethical matrix, and ideally both moral good and a more generalised flourishing (‘the good life’) is achievable.

This insight offers a powerful corrective to modern conceptions of freedom that emphasise individual choice while neglecting the social conditions necessary for it to be meaningful. Consumer culture often presents freedom as the ability to select between products, careers, or lifestyles. Hegel reminds us that genuine freedom requires social recognition and participation in communities that give our choices meaning. Hegel’s conception of Sittlichkeit– the ethical substance of a community – and his rejection of individualist moralism speaks to our condition. This doesn’t mean we can rest easy in the achieved ethical community: too much is wrong with what we have. Serious inequality threatens any kind of ethical substance, for instance, as does the endless drive for accumulation. But what is wrong isn’t mended by self-help, nor is it through the policing of words. It needs action, the very thing the beautiful soul of today shrinks from.

Books consulted:

Nietzsche:

The Gay Science (1882, 1887)

Beyond Good and Evil (1886)

The Genealogy of Morality (1887)

Hegel:

The Phenomenology of Spirit (1807)

Elements of the Philosophy of Right. (1820)