Sometime back in February I saw a gorgeous thing. Maybe it was February 6, when it happened. More likely it was a day or two later.

What I saw was the all-but simultaneous landing of a pair of booster rockets from SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy rocket. It pretty near took my breath away.

And then I saw that it was supposed to have a red Tesla roadster as its payload.

I say “supposed” because at first I thought I’d seen FAKE NEWS. Really, a Tesla roadster? How vain. It can’t be true.

But it was.

Then I learned that the Tesla contained a plaque inscribed with the names of over 6000 SpaceX employees. Much better, I thought, much better. And there was a plaque on the dashboard that said “Don’t panic”, homage to Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Someone has a sense of humor.

Elon Musk, the man behind this madness, explained: “I mean, it’s kind of silly and fun, but silly fun things are important. Normally for a new rocket they’d launch a block of concrete or something like that. That’s so boring. The imagery is something that’s going to get people excited around the world. It’s still trippin’ me out.”

OK. We’re good.

On with the show.

Freeman Dyson: Fantasy Unbound

I suppose the heavens have always been immeasurably vast; there are so many ‘things’ up there and, until quite recently, they’ve been beyond our grasp. We could see and, later on, count, but not touch. But it is only relatively recently that, putting the sun and moon aside, we’ve realized that those things are not all point objects–to be sure, some larger than others, but basically points. It was only in the early decades of the century that astronomers concluded that the more nebulous objects were in fact galaxies, like our own Milky Way. Suddenly the sky became populated with whole worlds of stars (some with planets of their own? and some of them with life?), each an immeasurable vastness unto itself, all unspeakably distant from us, and from one another.

It was during the era when astronomers were debating these issues, on December 15, 1923, that Freeman Dyson was born in England. He was fascinated mathematics and astronomy and by science fiction, especially Olaf Stapledon’s 1937 novel, Star Maker. He entered the Royal Air Force during the war, doing operations research for the bomber command. After the war he completed a degree in mathematics. He emigrated to the United States in 1947, dropped out of a doctoral program at Cornell, and embarked on a career as a scientific polymath, working in quantum electrodynamics, solid state physics, astronomy and nuclear engineering.

He did a lot of things, had a lot of ideas, and developed a reputation as contrarian.

In 1960 – three years, incidentally, after the Russians lofted the first man-made satellite – he speculated that, in due course, any intelligent species would enclose its home star with structures designed to capture as much energy as possible. Heroic engineering. These became known as Dyson spheres.

Not all of his ideas were so fanciful. His reputation has been built on a great deal substantial work. But it’s the fancy that interests me. One fantasy in particular.

A couple of years ago he reviewed three books about the near term prospects of space travel. He was unimpressed:

All three books look at the future of space as a problem of engineering. That is why their vision of the future is unexciting. They see the future as a continuation of the present-day space cultures. In their view, unmanned missions will continue to explore the universe with orbiters and landers, and manned missions will continue to be sporting events with transient public support. Neither the unmanned nor the manned missions are seen as changing the course of history in any fundamental way.

He concluded with a vision of his own, noting, appropriately enough, that “everything I say is pure speculation, a sketch of a possible future”. He suggests that “in the next few hundred years, biotechnology will have advanced to the point where we can design and breed entire ecologies of living creatures adapted to survive in remote places away from Earth.” He goes on to suggest that we propagate the Universe with Life:

The sun and the planets and moons contain most of the mass of our solar system. But for life, surface area is more important than mass. The room available for life is measured by surface area and not by mass. In our solar system and in the universe, the available area is mostly on small objects, on comets and asteroids and dust grains, not on planets and moons.

When life has reached the small objects, it will have achieved mobility. It is easy then for life to hop from one small world to another and spread all over the universe. Life can survive anywhere in the universe where there is starlight as a source of energy and a solid surface with ice and minerals as a source of food. […]

When humans begin populating the universe with Noah’s Ark seeds, our destiny changes. We are no longer an ordinary group of short-lived individuals struggling to preserve life on a single planet. We are then the midwives who bring life to birth on millions of worlds. We are stewards of life on a grander scale, and our destiny is to be creators of a living universe. We may or may not be sharing this destiny with other midwife species in other parts of the universe. The universe is big enough to find room for all of us. One writer who grasped the universal scale of human destiny was Olaf Stapledon, a professional philosopher who dabbled in science fiction.

Yes, not only changing the course of human history, but over millions and billions of years, changing the nature and texture of the universe.

I don’t know what I think of this vision. Dumfounded, speechless, flummoxed? No, not really. Giddy with joyous awe? No. He’s playing, but not my style of play. So what?

In a few months Simon Altmann, Sa’id Mosteshar, and Alan Smith replied to Freeman:

Another fundamental objection is to the belief that the universe is open to mankind. Considering humans’ degradation of earth’s environment, failure to avoid pollution, climate change, and the inequality between people, which makes the days of the pharaohs seem positively philanthropic, this seems preposterous. We should have learned from the devastating impact of introducing species into new environments on earth.

I understand that, yes, humans have had an unhappy effect on the earth’s environment, one that threatens us as well. But this seems ungenerous and mean spirited. In a reply that identifies his critics with Malvolio and himself with Sir Toby Belch, Freeman observes:

The finite speed of light ensures that no bureaucratic authority can be effective over large distances. Once life has escaped from this planet, it will be free to evolve and diversify as it pleases. We are a part of nature, and we will have the same freedom.

I am happy to hear views contrary to my own. I hope there will always be clashes of cultures. I hope there will always be Malvolios to engage Sir Toby’s wits. With thanks to my critics.

I like that: “We are a part of nature, and we will have the same freedom.”

Bill Benzon: Dreams and Reality

I don’t know when I first started thinking about space travel. Walt Disney had it on his evening TV show, which started in 1954 and there were science fiction movies, both in the theaters and on TV. But I have few specific memories of that.

The earliest thing I can put my finger on is this painting I did as a child:

There’s no date on it, but I’d guess I did it when I was eight or nine.

Perhaps a year or two after that I saw Forbidden Planet, a classic science fiction film that first showed in the theaters in 1956. It featured a flying saucer and Robbie the Robot. I drew picture after picture of both.

A year later, in the fall of 1957 my father took me outside. He pointed up to the sky and said “That’s Sputnik.” I’m not sure I saw the (moving) speck of light he was pointing to but I believed him. Yes, there was Sputnik up there in the sky. A man-made object going around the earth.

The first.

I was almost ten years old at the time. That’s the oldest event I can remember that is both important to me as an individual and important in the history of the world. No doubt I had some awareness of other important events as a young child, but I don’t remember them. This one I do.

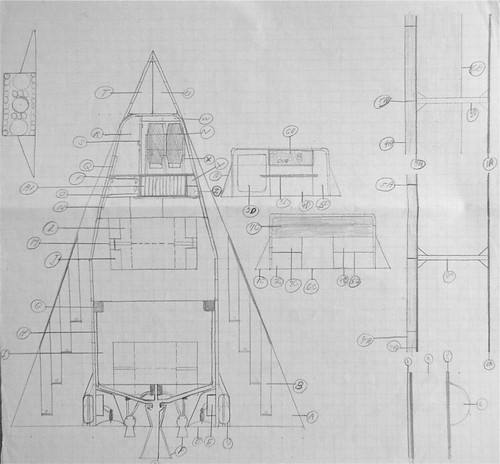

When I was a bit older, in my tween years, I built plastic kits of various things, including spacecraft. I also designed my own space ships. Here’s a fragment of one such design:

I’m sure I had a name for every one of the parts identified by a call-out, though I may not have written those names down anywhere. If I did, I no longer have those scraps of paper.

By the time I went entered college in 1965 I was no longer interested in designing rockets, much less in being an astronaut. By the time men first landed on the moon I’d become a quasi-hippie and was rather blasé about the space race. I doubt that I watched the moon landings on TV. A decade after that I read my way through a pile of science fiction while working on my dissertation (on cognitive science and literary theory). I enjoyed most of it and thought Samuel Delaney was the best of them, a fine writer by any standard.

I completed my degree in 1978 and took a job that fall at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in upstate New York. Established in 1824, RPI is the oldest technological university in the country. At the time George M. Low was the president. Low had spent most of his career at NASA, where he had been manager of the Apollo program and then Deputy Administrator.

I spent the summer of 1981 working with NASA. They’d decided their computer operation was not up to university standards and assembled a team of academics to draft a set of recommendations. I was on that team.

Our charge was peculiar. Yes, we were to come up with strategic recommendations to bring NASA’s computing infrastructure up to snuff. But there was something else at stake.

Morale at NASA was in bad shape and good people were leaving. The agency had been created to put a man on the moon. Yes, there were the scientific satellites too, but the spirit of the agency was bound up in the grand adventure of putting a man on the moon. Once that mission had been accomplished and further moon shots terminated, the spirit that had animated NASA began to die. The space shuttle had no pizzazz nor did the science missions.

I was surprised and a bit shocked.

Could we come up with some kind of sexy information technology stuff that would put some life back into the agency? That’s what NASA wanted us to do. The previous year, for example, NASA ran a summer study that dreamt up some “blue sky” computer based missions, including a plan to create an unmanned self-replicating factory on the moon. Did we think NASA should do something like that?

That all came back to me almost twenty years later – we’re at the brink of the new millennium now – when I stood there at Kennedy Space Flight center looking up at that Saturn V. It stretched from here to there. It was huge, but, up close, it didn’t look that big. And the Apollo capsule was tiny. To the moon, in that?

Yes. To the moon. In that. And back.

First the moon, then Mars, then the rest of the solar system. And then the stars. That’s what Walt Disney told us back in the 1950s. That’s how it was supposed to go.

But that’s not what happened. Landing a couple of men on the moon was enormously difficult, expensive, dangerous, and it had little practical value. The astronauts, scientists, and engineers may have been in it for the adventure, but the politicians allocated the money because it played well in the Cold War against the Soviet Union.

Once we’d won the space race, the political point had been made. There was no need for any more costly adventures of a non-military kind. NASA switched modes from Space Adventure, Inc. to Space Transportation, Inc. and fired space shuttles into low earth orbit.

The moon landing that was supposed to be the beginning turned out to be the end. But it was an end that left us at the threshold of a new world. Ever since then we’ve been trying to get our footing in that new world.

Elon Musk: To Mars or Bust

Telstar 1 launched on July 10, 1962 and relayed television pictures, telephone calls, and telegraph images; it also provided the first live transatlantic television feed – and inspired a hit by surf rockers The Ventures. It belonged to AT&T and was part of a multi-national effort involving the United States, the United Kingdom, and France. The commercial exploitation of near-earth space had begun, though it lagged a bit behind military usage. Near earth space is now richly populated by satellites serving a variety of commercial, military, and scientific purposes. None of these satellites were/are manned.

The original Star Trek series premiered in 1966 and the first Star Wars film came out in 1977. Both franchises continue to pump out new material while the old keeps circulating in various forms and fans produce and circulate their own media. And those are only the most prominent among tens of thousands of man-in-space stories that have been launched in the post WWII Space Age.

Apollo 11, though, was no fantasy. It landed on the moon on July 20, 1969: “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.” Apollo 17, the last manned trip to the moon, blasted off on December 7, 1972 and returned on December 19. Since then a number of men, and some women too, have lived in near earth orbit for varying amounts of time, but none have visited the moon, much less Mars or any other the planets of asteroids.

Elon Musk was born on June 28, 1971, in Pretoria, South Africa, after Apollo 11, but before Apollo 17. He would have been a year and a half old during Apollo 17, much too young to have experienced it in any meaningful way. For Musk, and for anyone born after the middle-to-late 1960s, human space-travel was something to be experienced only in science fiction. As something people actually do it existed only in historical retrospect.

Musk, among others, is determined to change that, profoundly.

By 1997 he had made his way to the United States by way of Canada (his mother was born there) and obtained undergraduate degrees in physics and business at the University of Pennsylvania. In 1995 he headed to Stanford for graduate work but left after two days to adventure as an entrepreneur in software, renewable energy, and outer space. The sale of his first company, Zip2, a web-based city guide, netted him $22 million in 1999. He continued in software, this time in payment services. He banked $165 million in stock from the sale of PayPal to Ebay. The year was 2002.

Now he had some serious money. He used it to found SpaceX (Space Exploration Technologies) in May 2002.

But now our little yarn gets complicated.

Musk became an investor in Tesla in 2004 and was appointed board chair. He took over as CEO in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and four years later Tesla shipped the first of its Model S sedans. In 2016 Tesla acquired SolarCity, which had be founded by two of his cousins and which is a major supplier of solar power systems in the United States. Tesla is a weapon against global warming.

Meanwhile, back on the launch pad…But you don’t really want the ins and outs, the ups and downs, do you? The launch vehicles (Falcon 1, Falcon 2, not even the mighty Falcon Heavy, we’ve already seen that one), the reusable Dragon spacecraft, the NASA contracts (very important, they paid the bills) – skip them. You want to go to Mars, don’t you?

So does Musk. But why? Writing in Aeon, Ross Anderson reports:

Musk enjoys making money, of course, and he seems to relish the billionaire lifestyle, but he is more than just a capitalist. Whatever else might be said about him, Musk has staked his fortune on businesses that address fundamental human concerns. And so I wondered, why space?

Musk did not give me the usual reasons. He did not claim that we need space to inspire people. He did not sell space as an R & D lab, a font for spin-off technologies like astronaut food and wilderness blankets. He did not say that space is the ultimate testing ground for the human intellect. Instead, he said that going to Mars is as urgent and crucial as lifting billions out of poverty, or eradicating deadly disease.

‘I think there is a strong humanitarian argument for making life multi- planetary,’ he told me, ‘in order to safeguard the existence of humanity in the event that something catastrophic were to happen, in which case being poor or having a disease would be irrelevant, because humanity would be extinct. It would be like, “Good news, the problems of poverty and disease have been solved, but the bad news is there aren’t any humans left.”’

Musk has been pushing this line – Mars colonisation as extinction insurance – for more than a decade now, but not without pushback.

I can understand the pushback, even sympathize.

But, ask yourself: What’s life going to be like in, say 2140? The date is not an arbitrary one, at least not on my part. That’s the year Kim Stanley Robinson chose for his marvelous New York 2140, a science fiction novel set in world that’s received two massive floods as a consequence of global warming and the sea is 50 feet higher than it is now. Fifty feet!

And yet the book is optimistic, if not exactly sunny and cheerful – 600 pages worth of detail. Things are certainly different. But the super rich are, if anything, even richer. Their aeries even higher. National governments are weaker, skyscrapers have food gardens on multiple floors, people are more self-reliant. Gray zones, if you will, are larger; boondocks abound. And living quarters for almost all are smaller. Life goes on.

But there’s nothing in the book about colonies on the moon, among the asteroids, or on Mars. Nothing. Robinson’s attention was elsewhere. But if Musk has his way, those colonies will exist. Their total population? I don’t know, 10,000, 100,000? Who knows? Will they be a net drain on earth resources? Maybe, but most likely not. They simply won’t happen if they cannot at least sustain themselves. If Elon Musk, and Jeff Bezos, and who knows who else, if they have their way, they’ll have to return a profit.

I wouldn’t bet on it. I wouldn’t bet against it. I just don’t know.

And, yes, the earth will still have been flooded.

Let me think on it.

Life goes on.

“You want to wake up in the morning and think the future is going to be great – and that’s what being a spacefaring civilization is all about. It’s about believing in the future and thinking that the future will be better than the past. And I can’t think of anything more exciting than going out there and being among the stars.”

Elon Musk, CEO and Lead Designer, SpaceX

The Blue Marble

This photograph was taken on December 7, 1972, by the crew of the Apollo 17 spacecraft, which was about 18,000 miles (29,000 kilometers) from earth at the time. This image quickly became a symbol of the environmental movement and has been reproduced zillions of times.