I have been thinking about artificial intelligence and its implications for most of my adult life. In the mid-1970s I conducted research in computational semantics which I used in analyzing Shakespeare’s famous Sonnet 129, “Th’ Expense of Spirit.” In the summer of 1981 I participated in a NASA study investigating ways to incorporate AI in NASA operations and missions. There I learned about an earlier NASA study that had looked into creating self-replicating factories on the moon.

I have been thinking about artificial intelligence and its implications for most of my adult life. In the mid-1970s I conducted research in computational semantics which I used in analyzing Shakespeare’s famous Sonnet 129, “Th’ Expense of Spirit.” In the summer of 1981 I participated in a NASA study investigating ways to incorporate AI in NASA operations and missions. There I learned about an earlier NASA study that had looked into creating self-replicating factories on the moon.

“Wow,” thought I to myself, “does that mean potentially infinite ROI?” How so? “Well, it’s going to cost a lot to develop the initial equipment drop and transport it to the moon, but once that’s been done, and those self-replicating factories and amortized the initial investment, it’s all profit from that point on.” That is, since the factories can replicate themselves without further investment from earth, we can reap the profits from whatever it is that these factories produce, other than more factories.

Now, whether or not that’s actually possible, that’s another question. But it was an interesting fantasy. That’s how AI is, it breeds giddy fantasies in those who catch the bug.

Somewhat later, and in a more sober mood, David Hays and I argued, “Sooner or later we will create a technology capable of doing what, heretofore, only we could.” We also pointed out that “We still do, and forever will, put souls into things we cannot understand, and project onto them our own hostility and sexuality, and so forth.”

There’s plenty of that going around these days. There’s a raft of AI hype that’s been floating around since ChatGPT’s release in late November of 2022. One prominent strain is telling us that we are doomed to be eradicated by an over-ambitious AI. I’m quite sure that that is projective fantasy.

Alas, the threat of massive economic displacement seems far more real to me, and more worrying. Jobs will be lost to AI – it’s already happening, no? – and, while new jobs will be created, it does seem to me that in the long run, job loss will inevitably outpace job creation. That should be a good thing, no? To live among material abundance without the drudgery of soul-destroying work, isn’t that something to be welcomed? In the long run, yes, but in the short and mid-term, no, it is not. We are not ready. We have become addicted to work, at least in the advanced world, and will have trouble adjusting to life without it.

That’s my topic for this column.

My Father in Retirement: Locked-in to work mode

There’s a scene that’s etched deeply in my mind. I was visiting my parents in the mid-1970s shortly after my father had retired. He was in the first cohort of workers who could retire on partial social security at age 62. I can only assume he retired because he was tired of working, because he wanted to spend his time in a more interesting way.

Now that his time was his own, what did he do? He put a small table in front of the television and planted himself there so he could play solitaire while watching TV. Reveal a card, look at the table, place the card on the table. Reveal a card, look at the table, place the card on the table. Reveal a card, look at the table, place the card on the table. Reveal a card, look at the table, place the card on the table. Repeat. He did that for four or five hours a day.

Why play solitaire when his time was his own? Who had stolen his life from him so that it was no longer his?

My father was a brilliant man with many interests. We was a superb craftsman. He made my sister a play-pen for her dolls. He made it from wood, and made it so you could fold it up, just like real playpens. It was, oh, 30 to 36 inches square when opened up. The real marvel was that he’d cut the letters of the alphabet, and the numerals 0-9, into the slats on the sides. He outlined each letter on the slat. Drilled a hole inside the letter. Put the blade of a coping saw through the hole and then reattached the blade to the saw frame. Then stroke by stroke he sawed out the letter or number. When that was done he used small pieces of sandpaper to finish the edges. But that’s only one of many things he built in his workshop.

He also collected stamps, thousands upon thousands of them. He played golf, a game he loved deeply. He liked music, liked to read, and was a good bridge player.

But when he had his time back, when he didn’t have to go into work five days a week, he filled these blocks of time with solitaire. Not with those other things he had previously reserved for evenings and weekends when he was not working.

In time, over the months and, yes, years, he cut back on the solitaire. He never did much, if any, wood working; the tools in his shop lay dormant. He played more golf and spent more time collecting stamps. The sale of his collection (after he’d died) was a minor event in the stamp-collecting world. He found some guys to play bridge with. And bought some records.

The solitaire never left him. Always the well-worn decks of cards. Hours and hours.

Why?

For one thing, work has you interacting with other people, a circle of people who interact with, day in and day out. When you’re retired, that’s gone, especially if you move away from your place of work. But there’s another problem; it has to do with what I’ve been calling behavioral mode. Work requires and supports a certain ecology of tasks, an economy of attention. You train your mind to it – though you might want to think of breaking a horse to saddle. When the job’s gone, that attention economy is rendered useless. But you’ve devoted so much time to it that you don’t know how else to deploy your behavioral resources.

The rise of retirement coaches

In time I learned that my father’s situation was not unique: In 2014 Kerry Hannon covered the issue for The New York Times, Finding an Identity Beyond the Workplace:

WHEN Guy Johnson retired from his tax management position at Unilever, one of the world’s largest consumer products companies, he was sure that he was prepared. But he was fooling himself.

“I lost myself when my wife, Barbara, and I moved to Sarasota, Fla., from Bergen County, N.J.,” Mr. Johnson said. “I planned my retirement financially, but I didn’t plan it otherwise.”

This summer, through weekly sessions with a retirement coach, Debbie Drinkard Grovum, the 68-year-old is working hard “to accomplish the goals in life that I’ve been putting off since I retired 10 years ago. She keeps me motivated.”

Thus retirement coaching has emerged as a profession:

New Directions, a coaching firm based in Boston, for instance, mainly focuses on coaching senior executives during their salaried years. But in the last five years, the number of people receiving retirement coaching at the company has probably tripled, Samuel C. Pease, a managing director and senior consultant at the firm, estimated.

More recently Hannah Seo wrote in Business Insider (December 11, 2024).

Dee Cascio, a counselor and retirement coach in Sterling, Virginia, says the growing urge to work in retirement points to a larger issue: Work fulfills a lot of needs that people don’t know how to get elsewhere, including relationships, learning, identity, direction, stability, and a sense of order. The structure that work provides is hard to move away from, says Cascio, who is 78 and still practicing. “People think that this transition is a piece of cake, and it’s not,” she says. “It can feel like jumping off a cliff.” […]

The idea that our personal worth is determined by how hard we work and how much money we make is deeply embedded in US work culture. This “Protestant work ethic” puts the responsibility of attaining a good quality of life and well-being on the worker — if you don’t have the time or resources for leisure, it’s because you haven’t earned it. […] This pernicious way of thinking prevents people from seeing purpose or value in life that doesn’t involve working for a paycheck.

What is going to happen as AI displaces more and more people from productive work? Sure, AI will create new jobs, but we have no reason that new job creation will be able, in the long run, to make up for displacement. For one thing, the new jobs will be quite different in character from the ones made obsolete. People who have lost their jobs to AI will not be able simply to switch into one of these new jobs. Retraining? For some of them, perhaps. But not for all of them?

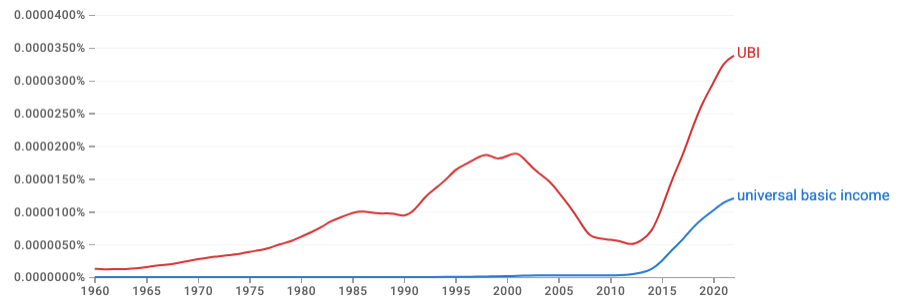

What about universal basic income (UBI), where people without employment are given a no-questions-asked income sufficient to take care of basic needs? As this Google Ngram chart shows, here’s been a lot of interest in it in recent years, especially since 2015:

That’s not going to solve the problem we’ve been discussing. Retirement coaching is not cheap, $75 to $250 an hour. UBI is not going to pay for that. In our present circumstances I fear that UBI is likely to become an indirect subsidy for the drug industry, either legal or illegal. As a culture we are addicted to work. By releasing us from work, I fear that AI will simply place us at the mercy of the worst aspects of that addiction. Will UBI in fact just be an indirect means of subsidizing drug industry, whether legal or illegal?

Keynes Diagnoses the Problem

Back in 1930 John Maynard Keynes saw the problem in his famous essay, “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren.” He predicted that we’d have a 15-hour work week.

For many ages to come the old Adam will be so strong in us that everybody will need to do some work if he is to be contented. We shall do more things for ourselves than is usual with the rich today, only too glad to have small duties and tasks and routines. But beyond this, we shall endeavour to spread the bread thin on the butter-to make what work there is still to be done to be as widely shared as possible. Three-hour shifts or a fifteen-hour week may put off the problem for a great while. For three hours a day is quite enough to satisfy the old Adam in most of us!

We’re nowhere close to that. Families where both adults have jobs are common, with one or both often working more than 40 hours a week. And yet they can’t make ends meet. And while AI holds out the possibility of changing that, perhaps in the mid-term, certainly in the long term, we’re not ready for it.

Keynes saw the problem clearly:

Yet there is no country and no people, I think, who can look forward to the age of leisure and of abundance without a dread. For we have been trained too long to strive and not to enjoy. It is a fearful problem for the ordinary person, with no special talents, to occupy himself, especially if he no longer has roots in the soil or in custom or in the beloved conventions of a traditional society.

Such is the case today. Social structures and institutions in the developed world are predicated on the centrality of work. Work provides most men and many women with their primary identity, their sense of meaning and self-worth. Without work we are greatly diminished.

The real challenge that AI presents to us, I believe is thus a challenge to our values. We live in a society organized to fit the needs of Homo economicus, economic man. Our best chance, perhaps our only chance, of realizing the value of AI and of reaping its economic benefits is to rethink our conception of human nature. Who is doing that? What think tanks have taken it on as their mission? What foundations are supporting the effort and trying to figure out how to turn ideas into social and political practice?

Remember the Sabbath…

Work, however, is not the only source of meaning in life. There is religion. Back in 2022 Ezra Klein interviewed Judith Shulevits about rest and the Jewish Sabbath. In his introduction he observed:

But the Sabbath is a much more radical approach to rest than a simple respite from work and technology. Implicit in the practice of the Sabbath is a stinging critique of the speed at which we live our lives, the ways we choose to spend our time and how we think about the idea of rest itself. That, at least, is a central argument of Judith Shulevitz’s wonderful book, “The Sabbath World: Glimpses of a Different Order of Time.”

Early in the interview Klein asks Shulevitz about all the rules associated with the Sabbath:

I would argue that they’re trying to create meaning. I think of all the rules around the Sabbath telling you to stop doing things, which are the should-nots, as creating a kind of frame, if you think of it in space rather than in time, or you think of a frame in time rather than in space, or you could think of it as a proscenium around a stage, or you could think of it as a break after a line of poetry.

These are things that create meaning. They bound time and say this is going to be special. Now we’re going to make something extraordinary out of the ordinary. Because the ordinary stuff of a Sabbath isn’t that extraordinary, right? You’re supposed to have a meal. […] You are supposed to come together. In a Christian idiom, I’d say you’re supposed to break bread. So you’re supposed to be collective.

You are supposed to let your mind wander. We’ll gather, have a moment of just letting go. Not all the time, some of the time. But these are the positive things that the frame gives a special gloss to the way it does a work of art and says, this space here, it’s meaning. Make sense of it.

Notice that, “let your mind wander.” That’s the very opposite of work mode, where you are focused on the task at hand, a task assigned to you by someone else, or by an impersonal corporate agency. Moreover, it is but one task is a large assemblage of tasks, almost all of which are out of your ken. You are a cog in a corporate wheel.

But not on the Sabbath. Your mind is free to wander, and to wonder, not only in the sense of questioning, but in the sense of awe and amazement. These people are my friends and family. Here before me and around us, this flower, that rock, those clouds, the dog, the birds, this is our house, our community, this is God’s world, our world.

Shulevitz observes:

So these rules — you could almost say these rules are to safeguard the world from man, but also to safeguard you from being an eternal slave — today, we would say, of the clock — in the deep past, we might have said from the struggle to survive.

Happiness Beyond GDP

I regard the question of work as one facet of the general problem of happiness. Happiness, in turn, has recently been studied under the general rubric of flourishing. Initiated in 2021 by Baylor University, the Human Flourishing Program at Harvard University, Gallup and the Center for Open Science, the Global Flourishing Study (GFS) studied over 200,000 individuals in over 20 countries. The objective is stated simply: Where are people the happiest and why?

If you are interested in human flourishing then you need a complete picture of how people live, not just the gross domestic product (G.D.P.) of the nation in which they live. GDP may give you a crude measure of material prosperity, but it tells you little about how people live. As such measures go, it’s relatively easy to assess as it is based on economic data that is routinely collected and readily available.

To evaluate flourishing the GFS used various “research lenses” that took into consideration A) happiness and life satisfaction, B) mental and physical health, C) meaning and purpose, D) character and virtue, E) close social relationships, F) financial and material stability, and G) religion and spirituality. Crazy, no? Yes, but necessary.

Three of the investigators, Byron Johnson, Tyler J. VanderWeele and Brendan Case, recently published some initial results in The New York Times. What did the study find?

Sweden, for example, had high scores for life evaluation, behind only Israel, another typical standout in the World Happiness Report. When we widened the aperture, however, the picture changed: Sweden had only the 13th-highest composite flourishing score, essentially tied with the United States, and considerably lower than Indonesia, the Philippines and even Nigeria, whose 2023 gross domestic product per capita was just under 2 percent of America’s.

Across the whole sample of 22 countries, the overall national composite flourishing actually decreased slightly as G.D.P. per capita rose. The only high-income countries that ranked in the top half of composite flourishing were Israel and Poland. Most of the developed countries in the study reported less meaning, fewer and less satisfying relationships and communities, and fewer positive emotions than did their poorer counterparts. Most of the countries that reported high overall composite flourishing may not have been rich in economic terms, but they tended to be rich in friendships, marriages and community involvement — especially involvement in religious communities.

The bottom line, to borrow an idiom from Homo economicus (economic man): Civilization isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. Johnson, VanderWeele, and Case “wonder whether prioritizing economic growth and material prosperity above all else has imposed costs on developed nations — and whether doing so is likely to impose these costs on the developing economies that follow the path of Europe and its colonial offshoots.”

How can AI best contribute to human flourishing?

In view of the preceding arguments, I do not know. Yes, eliminate labor. But that is not sufficient.

We must reconceive the purpose – or is it purposes? – of life. Yes, work will remain, at least for some, contributing to material well-being. There is religion. While I am a thoroughly secular person, I see no reason why everyone should be so. And there is family, our children and their children. Most simply put, we have our communities and the beliefs and activities that support and sustain them.

These have always been with us. The problem is to shape these activities, these callings, into a coherent worldview and then to embody that worldview in social institutions. That’s a job for philosophers and writers, certainly. But also politicians, diplomats and statemen. Artists, musicians, poets and novelists, film-makers and game-crafters. Gardiners and seamstresses, cooks and teachers, nurses and machinists. How about everyone? That, I believe, will be the work of generations and it will change the way we live as surely as the Industrial Revolution began doing over two centuries ago.

* * * * *

About the image: I created it with ChatGPT. I uploaded an early draft of this article and asked it to create an appropriate illustration. It suggested a program for the image, which I then approved. It produced an image. I then worked with it to modify that initial image until I was satisfied. The image I used is the sixth one ChatGPT created.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.