by Angela Starita

Teddy lives in two houses. They’re equally bereft of taste–good or bad. Teddy’s a dog and his nominal doghouse is inside the house of his owner, Jonathan. It’s built inside the closet under a stairway, with its entrance, the side facing Jonathan’s living room, covered in pale rusticated stone.

Jonathan calls it “the world’s most famous doghouse.” In interviews on feel-good segments of news shows, he refers to Teddy as “the world’s most famous dog” and explains that he himself is “blessed with a creative mind.” This last is in reference to the scenarios he dreams up for TikTok videos that feature Teddy as a Rabelaisian prankster interested only in buying toys and treats with Jonathan’s credit card, watching movies, and playing video games. He spends an inordinate amount of time on a couch.

It’s Teddy’s house that launched him to fame. Jonathan had been making DIY construction videos, and the one that garnered the most views was the closet-to-doghouse conversion. It had hit some collective nerve, the one that delights in miniatures and accounts for the popularity of dollhouses and children’s beauty pageants. Its fitted with a couch, shelves for photos a copy of PlayDog, and a television over a faux fireplace. My favorite of the videos has Jonathan crawling inside for Teddy-hosted sleepovers.

In the two years I’ve been watching Teddy videos, the mise en scene has moved from the doghouse to what I presume is Jonathan’s actual house, a place as scared of distinction as the model home developers “stage” for potential buyers—sparsely furnished in off-whites with names like Chantilly Lace and White Dove. Predictably, the first floor is an open-plan centered around a beige sectional sofa facing a high-definition television. Occasionally there are shots of a dining “area” and, in a behind-the-scenes video, Jonathan shows off his home gym, a room with a treadmill and other equipment. He and Teddy sometimes watch movies in the “home theater” a room with swollen, black recliners presumably facing an even larger screen.

When the action moves outside, the setting is equally blank. The large houses are all set far apart separated by gray expanses of grass and the occasional spindly sapling. There’s a built-in pool and, the most notable landmark, John’s big black SUV, which Teddy commandeers in the interest of buying more toys or picking up burgers. Most times, though, Teddy and Jonathan–along with two other dogs–live in the large house watching television and getting Amazon deliveries.

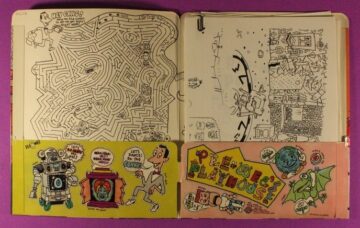

I found myself thinking about Teddy’s bloodless world a few weeks ago when watching “Pee-Wee as Himself,” a documentary about Paul Reubens and the outsized impact of two arrests on his career and personal life. For his TV show, Reubens famously filled Pee-Wee’s house with animate furniture, toys, oddball gadgets, unexpected doorways, niches, and windows for puppet or human friends to momentarily drop in. I never went to a Montessori school, but my idealized version of one includes “stations,” areas dedicated to different activities—drawing or writing or building computer circuits—where attendant supplies could stay out for the duration. That’s what I loved about Pee-Wee’s world, the possibility of switching from one fun thing to the next without interruption. At the same time, the sheer amount of stuff in the playhouse always scared me—too chaotic, too many choices.

Certainly, Jonathan (and the many other interiors seen in TikTok reels) offer no such stimulus. With their gray, faux-wood tiles and blank walls and seasonal flags, they seem to offer nothing at all, no visual equivalent of a fingerprint or a retinal scan: no trace. Teddy’s antics can be idiosyncratic or “creative,” to use Jonathan’s word but the setting is anything but. The interiors of those houses are reminiscent of Joan Didion’s description of Ronald and Nancy Reagan’s governor’s mansion, what she called “an enlarged version of a very common kind of California tract house, a monument not to ego but to a weird absence of ego, a case study in the architecture of limited possibilities, insistently and malevolently ‘democratic.’”

Though I loved Pee-Wee’s Playhouse during college, I knew little of Reubens after his first arrest, the exposure-at-a-porn theater one. The response to his “crime,” of course, was absurd but as he pointed out in an interview not used in the documentary, he’d so successfully hidden himself behind the Pee-Wee character, that no one had an image of Reubens himself until the infamous mug shot. Too stark a contrast of images.

But what’s even more poignant in the Reubens’ story is the second arrest for possession of child pornography, an arrest that required Reubens to register as a sex offender. The material in question—according to the film, it came down to one photo of a young man (possibly underage) seen from the shoulders up—was part of a collection of vintage erotica and muscle magazines, part of Reubens’ obsessive collection of …. everything. Toys, plates, books, paintings, records, anything funny or weird or reminiscent of the Atomic age and its excesses. Reubens’ fervent collecting, interpreted by Gary Panter for the set of the television show, proved dangerous, a vulnerable underbelly. Reubens hid behind Pee-Wee but in designing physical spaces—both for himself and his best know character—he refused the anonymity afforded by Chantilly Lace and that was his undoing.