by Eric Feigenbaum

At about 6:30 am, we pulled up to the Labor Ready office in the Central District. My friend – who for the sake of this column will be called Rick – and I were responding to a trespassing call: a woman who was asked to leave the day-labor agency office was refusing.

At about 6:30 am, we pulled up to the Labor Ready office in the Central District. My friend – who for the sake of this column will be called Rick – and I were responding to a trespassing call: a woman who was asked to leave the day-labor agency office was refusing.

Now to be clear, I wasn’t a cop – but Rick was and when I would return to Seattle on a break from working in Singapore – the best way to spend time with him was to go on a “ride along”. To make it work better, Rick told people I was a plain clothes officer. To mitigate risk, I spoke little and appeared stoic.

We entered the Labor Ready office, prepared to find an altercation in progress, only to discover a 30ish, short, heavy-set Filipina lady standing in the waiting area talking to herself. The staff told us they had asked her to leave, but she didn’t really seem to understand them.

Rick asked the woman if she could follow him outside and she complied. Through the din of voices in her head, she was able to answer most of Rick’s questions – although not always accurately. We were able to ascertain the woman thought she was Princess Diana, but also had some sense she was reporting for a day-labor assignment. She was aware she wasn’t quite right and articulated that she needed medication – only she had run out and couldn’t afford more.

Protocol said Rick should have issued the woman a Trespassing Card and sent her on her way. That didn’t feel like the right thing to do for this very nice woman clearly struggling with her mental health and trying to make a living. Alternatively, he could have gone heavy and decided to arrest her for trespassing – another path to medication, only through the jail’s healthcare system. But then she would have an arrest on her record and been imprisoned for doing nothing more than talking to herself.

Instead, Rick took liberties to do the right thing and gave the woman a ride to the nearby county hospital where she could get treatment and free medication. She was able to tell us she had been to Harborview before, and they would likely have record of her. Sadly, the woman lost her day’s wages – but avoided the perils of both unaided freedom and jail.

In my years of being a “plain clothes officer” of Seattle’s East Precinct in the mid-to-late aughts, I found the vast majority of our time was spent interacting with mentally ill and addicted people. Trespassing was the most common call we received and the second most common thing we did was arrest vagrants who had bench warrants for failures to appear on drug and alcohol-related charges.

Many of the people we arrested didn’t mind – they were on their way to a bed, shower, meals and healthcare. In much of America, jails perform the function state mental healthcare facilities once did. Rotating between jail and the streets – or if they were lucky in and out of Harborview – was life for too many people in Seattle’s East Precinct.

In my home on the other side of the ocean, there was no homelessness. You will never see a person living on the street in Singapore. MAYBE about as often as Haley’s Comet comes around you might see someone talking to themselves.

That’s because Singapore considers homelessness inhumane. Singapore’s answer?

Give well-coordinated government-sponsored support to families with mentally ill members and if that doesn’t work, place those who can’t care for themselves in Singapore’s 2010-bedded Institute for Mental Health which features 50 inpatient wards and seven outpatient specialty clinics. IMH also runs satellite clinics throughout Singapore as part of supporting patients to live with family or independently.

Moreover, when Singaporeans are arrested under the influence or in possession of illegal drugs, the state mandates drug and/or alcohol treatment.

Interestingly, many Americans and other Westerners consider Singapore’s approach to mental illness inhumane. And herein lies the rub.

The difference is rooted in history. Beginning in America’s “Progressive Era” surrounding the turn of the 20thCentury, the creation and development of psychiatric facilities was a major humanizing advancement. Unfortunately, any system in which a population is deemed incapable of making decisions and having their agency taken away becomes immediately vulnerable. Like prisons, workhouses and orphanages, psychiatric hospitals attracted a fair number of predatory, sociopathic and sadistic employees. With a still nascent understanding of psychiatry and neurology – the unfortunate result was that despite whatever good was intended and even done – abuse and horrific treatments also occurred.

We’ve all seen or read One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest and Shutter Island.

America, Britain and a number of other developed countries took the lesson that involuntary commitments were a dangerous thing and that human dignity requires respecting individual rights – even of those who may not choose what benefits them.

Certainly, there are stories of people wrongly being wrongly diagnosed or even punitively called crazy. Determining someone else’s interior state is complicated and necessarily involves some subjective evaluation. There’s no blood test for psychosis.

On the other hand, vast numbers of people with their rights fully intact live in tents and shopping carts along highways, parks, parking lots and sidewalks throughout urban America.

At some point, a society has to make some kind of utilitarian calculation around how to handle mental illness and addiction. What is crueler – wrongfully involuntarily admitting someone who doesn’t need it, or leaving someone who desperately needs help on the streets?

There are also critical questions around inpatient care. Are we simply locking up problematic and embarrassing people and throwing away the key or are we keeping the vulnerable safe and giving them care they can’t give themselves? Is a schizophrenic without family care and support better off on the streets or in a ward?

There are no clear, fail-safe answers. For both individuals and their societies, stripping people of their agency is a dangerous business – as is leaving people to live unhoused lives.

Singapore’s system relies on trust and integrity. People have to trust the good intentions and judgment of social workers, doctors, nurses and officials. There has to be a belief in institutions – literal and figurative. Singapore with its high transparency ratings (98 out of 100 on government control of corruption and 100 of 100 on effectiveness of government in 2024), collectivist values and strong family units has an easier time believing its experts and officials are working in patients’ and society’s best interests.

Meanwhile upheaval in America and the Western world has people more distrusting than ever in traditional institutions with the Pew Research Center finding in Spring 2024 that only 22 percent of Americans trust the Federal Government to do the right thing.

Of course, government can’t do nothing with the addicts and mentally ill that form much of the homeless population. Even without state psychiatric facilities, we may be more of a lock and key society than the average person realizes.

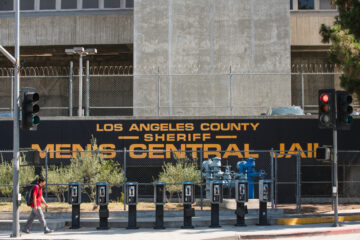

My current hometown, Los Angeles, is an even better example of this. The Los Angeles County Jail system is not only the largest in the country but has the largest medical program of any jail system. In fact, Los Angeles County Correctional Health Services operates 26 health centers and four acute care hospitals, employing 23,000 staff at an annual cost of $6.2 billion per year.

As of the end of 2022, 43 percent of the inmate population was receiving mental healthcare and 20 percent were diagnosed with a serious mental illness. Additionally, LAC CHS provides Medication-Assisted-Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder to thousands of inmates not classified as receiving mental health services.

One way or the other, we still strip the mentally ill and addicts of their rights – only after they commit a crime.

Some progressive cities in America – including Portland and Seattle – are now partnering with nonprofits who provide counseling and addiction services rather than locking people up. The effectiveness of these relatively new programs remains unknown, though severe homelessness continues to plague both.

At first glance, the thought of a 2010-bedded mental healthcare facility in Singapore may conjure up Nurse Ratchet nightmares. But is that worse or scarier than 5,527 inmates in LA County Jail receiving mental healthcare services?

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.