by Michael Liss

Words, so many words. Words that inspire “Ask Not,” and those that call upon our resolve “[A] date that will live in infamy.” Words that warn about the future “[W]e must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex,” and those that express optimism about it “I’ve been to the mountaintop.” Words that deny their own importance “[T]he world will little note nor long remember what we say here,” while elevating themselves and the dead they honor to immortality.

Words, so many words. Words that inspire “Ask Not,” and those that call upon our resolve “[A] date that will live in infamy.” Words that warn about the future “[W]e must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex,” and those that express optimism about it “I’ve been to the mountaintop.” Words that deny their own importance “[T]he world will little note nor long remember what we say here,” while elevating themselves and the dead they honor to immortality.

These words, these good words. They are the building blocks of our civic culture. In a democracy like ours, where we do not demand conformity, but rather abide by rules that are essentially an exchange of promises, words are paramount. What do they mean, how binding are they, do they express an unbreakable eternal truth, or do they grow sclerotic, even obsolete? If so, how do we change them? Is there an essence, a central truth that is and must be immutable?

To get any of those answers, we should begin with Jefferson, the central designer and primary wordsmith in the architecture of independence.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Wonderful, isn’t it? Thrilling. It is our intellectual origin story. It should fill us with pride—that, for these principles, we took on the most powerful nation on Earth and, after years of reversals, won. Soon we will celebrate the 249th Anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. We can trot out some nerdy historian to point out that maybe it’s not really the 4th of July—maybe it’s the 2nd or 3rd. We can indulge ourselves in cautionary reminders how perhaps we haven’t lived up to the promises that are in the Declaration. We can certainly bewail the state of contemporary politics. Or we can just enjoy it, maybe go to a small town if we don’t live in one, see the old cars and the pride of the older soldiers, the flags and bunting, the picnics, the fireworks, the tradition of a 4th of July speech by some local worthy.

Blather—of course it is. Like everything else, we commoditize it, commercialize it, invariably bury the lead: At its best, Independence Day should be a reaffirmation of the Declaration’s central promise. As, at Gettysburg, Lincoln drew the line back four-score and seven and dared to look forward to “a new birth of freedom,” so we too, all of us, should draw strength and purpose from our past to preserve our political heritage and extend it to the next generation. We are all equal, all endowed with certain unalienable rights. No government, no officeholder, no matter how high, has the right to take them from us.

More blather. I know it. Lincoln was, in some respects, wrong at Gettysburg in relation to Jefferson. I’m wrong here in proposing that the Declaration’s assertion of not-to-be-touched unalienable rights is anything more than aspirational. Man may have been “born free” in 1776, but, by 1789, he had voluntarily adopted the “chains” of the Constitution. What we discovered between 1776 and 1789 is that, if Jefferson had constructed an inspirational obelisk of freedom with symbols etched in its sides, it was (mostly) James Madison who wrote the instruction manual. To live “free” in a frequently difficult world, challenged by more powerful adversaries, and to mediate differences between the different states and regions, we needed (and continue to need) a functioning government. The more we cede to the government, the less free we are.

Lincoln did understand the Constitution’s centrality. Over and over, he had used a rule-based argument: Slavery could be protected where it existed because that was what “our forefathers” had agreed to, but geographically restricted because that was also what our forefathers had agreed to. The careful lawyer’s brief he laid out at Cooper Union was meticulous in its logic; slavery was odious, but that did not make it necessarily illegal. A country of laws needed leaders who would obey those laws, and he, Lincoln, would respect the Constitution. His First Inaugural repeats it: “I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.”

What about the Emancipation Proclamation? In Lincoln’s opinion, it was justified as a war measure against those states that had refused to abide by their obligations under the Constitutional contract, and only those states. But the “new birth of freedom” at Gettysburg, no matter how soaring the words, couldn’t occur without a Constitutional Amendment to ban slavery nationwide. Lincoln may have drawn his inspiration from Jefferson, he may have evolved in his willingness to follow a more abolitionist path, but he stayed true to his adherence to a rules-based Constitutional solution.

Jefferson had a different idea. The rules-to-freedoms ratio shifted with each new intrusion, and Jefferson, a man who believed (devoutly) in his ability to govern himself and others, was suspicious. Constitutions—all constitutions—worried him. Even with the best of intentions, the greatest foresight, one generation of men should not be permitted to bind another. In a September 6, 1789 letter to Madison that toyed with the expiration of a Constitution after 19 years, he wrote:

On similar ground it may be proved that no society can make a perpetual constitution, or even a perpetual law. The earth belongs always to the living generation.

As to our Constitution, Jefferson wasn’t in Philadelphia for its drafting, didn’t see its precise language until after near-completion, and had a role largely limited to back-channeling with Madison (from across the Atlantic) and lobbying for the Bill of Rights. Madison had the pen, and while he and Jefferson were allies and friends, the Constitution could not reflect Jefferson’s—or any man’s—personal preferences in full. No rulebook for the distribution of responsibility—and perhaps more importantly, power—could. At best, the rulebook could reflect an imperfect but acceptable series of compromises.

If you go back to Jefferson’s words, and fast-forward to the Constitution itself, you can see an inherent conflict. Jefferson was for a particularized kind of freedom. All men may have unalienable rights, but that didn’t always mean for self-government. Jefferson clung to an agrarian ideal—America should be a nation of farmers, not city-dwellers, because that is where virtue lay. His early drafts of a Constitution for Virginia limited suffrage to landowners. All men may be created equal, but they were not all necessarily endowed with the intelligence and character to lead. Jefferson was, and he had no intention of being among the governed.

This wasn’t something that just came to him when faced with the latest from Philadelphia. In his “Notes on Virginia, 1781-1782,” he griped, “An elected despotism was not the government we fought for.” That “elected despotism” concerned the allocation of seats in Virginia’s bicameral legislature. In Jefferson, there was this core duality. He cared deeply about individual liberties, the poetry of democracy. He worried constantly about intrusions, about the undue exercise of power, the testing of what we would now call “guardrails.” But he was also quite capable of seeing his personal interests and preferences as completely consistent with the needs of the many. His eight years as President surely showed no marked deference to popular opinion or political opposition—his Embargo Act, for example, was widely disliked, and bad policy.

There was a “temperament” to Jefferson. He was possessed of extraordinary gifts in which his countrymen placed their trust; he had the highest ideals, but he often followed his own star. The man could, and did, play the game. He could, and did, act publicly and boldly, and then conspire behind closed doors. He was not always conventionally loyal. He whispered, and, to an extraordinary degree, his listeners often acceded to his wish for anonymity. For decades after his two terms in the White House, bits and pieces of untold stories would be revealed in old letters and forgotten documents.

One such was his role in drafting the Kentucky Resolution. Last month, I wrote about the Alien and Sedition Acts. To double back for a moment, in 1798, war between America and France seemed likely, and the ruling Federalist Party, apparently equating political disagreements with disloyalty, passed four bills intended to stem immigration by people who might side with France (and/or the Democratic-Republican Party) and criminalize criticism of the national government. President John Adams signed them, marking for all time an extraordinarily unwise abuse of power. Enforcement was entirely partisan.

Much of the public (including some Federalists) reacted with a mixture of outrage and amusement (Adams was a very easy man to mock). But two of the most prominent Democratic-Republicans, Madison and Jefferson, went further. Both men realized that the Acts were not only a serious threat to democracy, but political gold. The Acts had to be opposed, and so they began drafting formal legislative responses—Madison, for Virginia, and Jefferson for Kentucky. Jefferson’s participation in particular was kept secret—it had to be, as he was the Vice President. Kentucky’s John Breckinridge introduced Jefferson’s work without attribution, leaving the inference that he, Breckinridge, had been the author.

The path was harder than they anticipated. First there were legislative hearings in both states. Madison’s draft was generally given a gentle treatment, but, in Kentucky, Jefferson’s words got a working over. Compare Jefferson’s original draft to Kentucky’s final, and there are marked differences in both tone and content. Still, both men thought they had accomplished their goals—the Resolutions were both adopted by their respective states, and, with an expectation of a groundswell of support, then sent on to the remaining 14 states, asking them to concur.

To Madison and Jefferson’s surprise, they found no takers. The public in general did not like and openly disparaged the Acts, but they were not prepared to adopt the language in either the Virginia or Kentucky Resolutions.

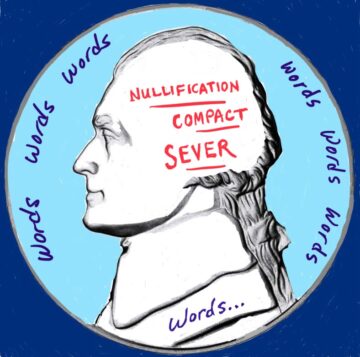

Why not? It turns out that both men had misjudged the market. The “cure” they proposed for the disease of Federalist overreach went beyond what many would tolerate. Its toxicity can be summed up in two of Thomas Jefferson’s words: “Nullification” and “Compact.”

Jefferson proposed to have Kentucky, and any other state ready to join in, simply “Nullify” any Federal law it disagreed with. Jefferson called it a “rightful remedy.” What about the Constitution’s Supremacy Clause?

This Constitution… shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.

Not a problem when you apply the concept of “Compact.” Per Jefferson, the Constitution was adopted by the states, each one of which had the ability to judge for itself the Constitutionality of any and all federal actions. As to the Alien and Sedition Acts specifically, Jefferson‘s draft called them “altogether void and of no force.”

This was dynamite. If states had the unrestricted right to pick and choose which Federal laws to obey, then there would be no federal government. Madison, during ratification debates in 1787-88, had consistently made the claim that “We the People” meant exactly what it said. The people, all of them, were making the choice to move to a written Constitution. His insistence seemed almost didactical, but there was sound reasoning for it. He wanted consent of the governed, and the governed were the people, and not the states. Now, to combat the Acts, he was sliding away from that, not as noisily as Jefferson, but sliding nonetheless. Nullification broke the contract that derived from consent.

Madison moved quickly to clean up the mess, first explaining that the Virginia Resolution didn’t exactly call for a Nullification by a state, merely that the state could “interpose” its judgment between the federal government and the people. Later, he would pen a “Report of 1800,” which would be adopted by the Virginia legislature. The Report would bring even more nuance—away from the Compact Theory and raising the bar substantially to justify an “Interposition.” He would not exactly define what an “Interposition” might actually be.

But Jefferson was fired up. He was furious at Adams, deeply disturbed by the text of the Acts, and convinced there was a plot to make Federalist domination of the government permanent. In an August 23, 1799 letter to Madison, he said,

[T]he good sense of the American people and their attachment to those very rights which we are now vindicating will, before it shall be too late, rally with us round the true principles of our federal compact; but determined, were we to be disappointed in this, to sever ourselves from that union we so much value, rather than give up the rights of self government which we have reserved, & in which alone we see liberty, safety & happiness.

There it is. “Sever ourselves.” I’d include an exclamation point but one is clearly implied. There we have it. Thomas Jefferson, one of the Mount Rushmore Four, talking about Nullification and…Severing.

Sever, as in “walk out” over a dispute about legislation. Just one word, one crazy, outlandish word that, along with “Nullification,” seemingly died a quiet death as three of the four Acts expired, and the people, all of them, elected Jefferson to be the third President of the United States.

But the virus of Nullification and Compact Theories and Severing didn’t die. Instead, it entered the bloodstream of American politics, and, when the secret of Thomas Jefferson’s involvement in the Kentucky Resolution began to tease itself out, legitimized it.

Three decades later, John C. Calhoun, himself a sitting Vice President, would suggest the same things—calling Jefferson his spiritual predecessor. These words would repeat themselves before the Civil War, especially from aggrieved Southern states, whenever the word “slavery” would be uttered. They would be used as a pretext for secession after Lincoln’s election in 1860: they are present in my facsimile copy of 1867’s The Lost Cause, by E.A. Pollard, the Editor of the Richmond Examiner. They would morph, deftly, into “States Rights” arguments for decades afterwards. They are the original genetic material for every grandstanding Governor or Attorney General who wants a national profile and seeks to overturn a law or even an election result with which he doesn’t agree.

That’s unfortunate, because Jefferson, subtle or not, publicly or not, wisely or not, was raising an important point. What are the remedies for unjust laws or unjust Presidents, or even unjust Supreme Court Justices? How much overreach do they get—is it limitless? How do states protect themselves and their citizens when the 9th and 10th Amendments are being ignored? How do citizens defend their rights when the Bill of Rights is being shredded?

What words might Thomas Jefferson have? It’s worth exploring.

Author’s note: You can find a great deal of original source material at the website https://founders.archives.gov/

John Adams Is Bald and Toothless: A Brief History Of The Alien And Sedition Acts

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.