by Laurie Sheck

1.

In her 1925 essay, On Being Ill, written when she was 42 years old, Virginia Woolf speaks of the spiritual change that illness often brings, how it can lead one into areas of extremity, wonder, isolation. “How astonishing, when the lights of health go down, the undisclosed countries that are then disclosed, what wastes and deserts of the soul….”

The body is no longer a site of comfort and familiarity but “this monster…this miracle.” Overwhelming, weird, intense, mysterious. And with this sense of estrangement from one’s familiar, healthy self, there often comes a profound isolation that colors the whole world, “Human beings do not go hand in hand the whole stretch of the way. There is a virgin forest in each; a snowfield where even the print of birds’ feet is unknown.” It is a stark and desolate image. A cold whiteness without the barest trace of interruption. It is a world stripped to its core.

In illness “we cease to be soldiers in the army of the upright; we become deserters.”

Daily life becomes a strange, exotic place. Longed for, various, remote. The unreachable land of ordinary habits, activities, frustrations, pleasures.

2.

Particularly since the pandemic, I have thought often of Woolf’s essay, and of Elaine Scarry’s seminal work, The Body in Pain, where she writes of the way “physical pain has no voice.” “Whatever pain achieves, it achieves in part through its unsharability.” This opacity to others outside oneself is a significant part of its cruelty. This applies, too, to the often relative invisibility of certain maladies, like Long Covid. And in that gulf between appearance and reality, between the self and others, a terrible knowledge arises. “One aspect of great pain…is that it is to the individual experiencing it overwhelmingly present, more emphatically real than any other human experience, and yet is almost invisible to anyone else, unfelt, unknown.” What Scarry writes about pain can also apply to many other aspects of bodily unwellness.

She compares the experience to a human being “making a sound that cannot be heard.” Read more »

The Paradox

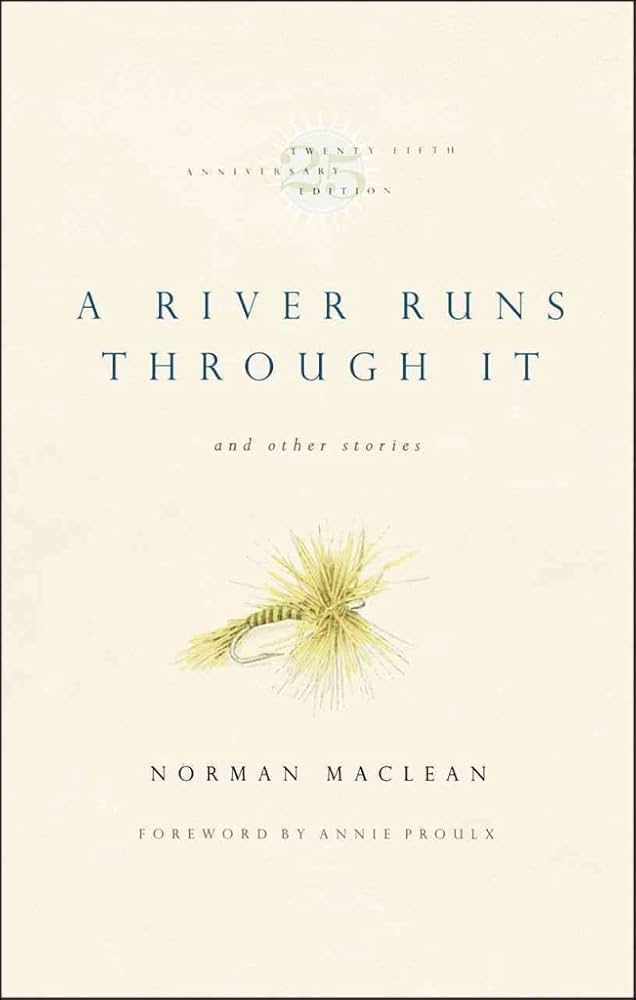

The Paradox Three weeks later and I’m almost fully healed. My ribs still hurt when I lie down to sleep and when I rise in the morning, but sitting and walking are fine. In another week I’ll be able to return to the gym and attempt some light weightlifting, a welcome resumption of my weekly routine. There was, however, a silver lining to my accident. In the days immediately following it, I could do little else but read. Sitting down in a chair, I was stuck there. So it was that I took A River Runs Through It (1976) by Norman Maclean off the bookshelf in my father’s office and began to turn its pages.

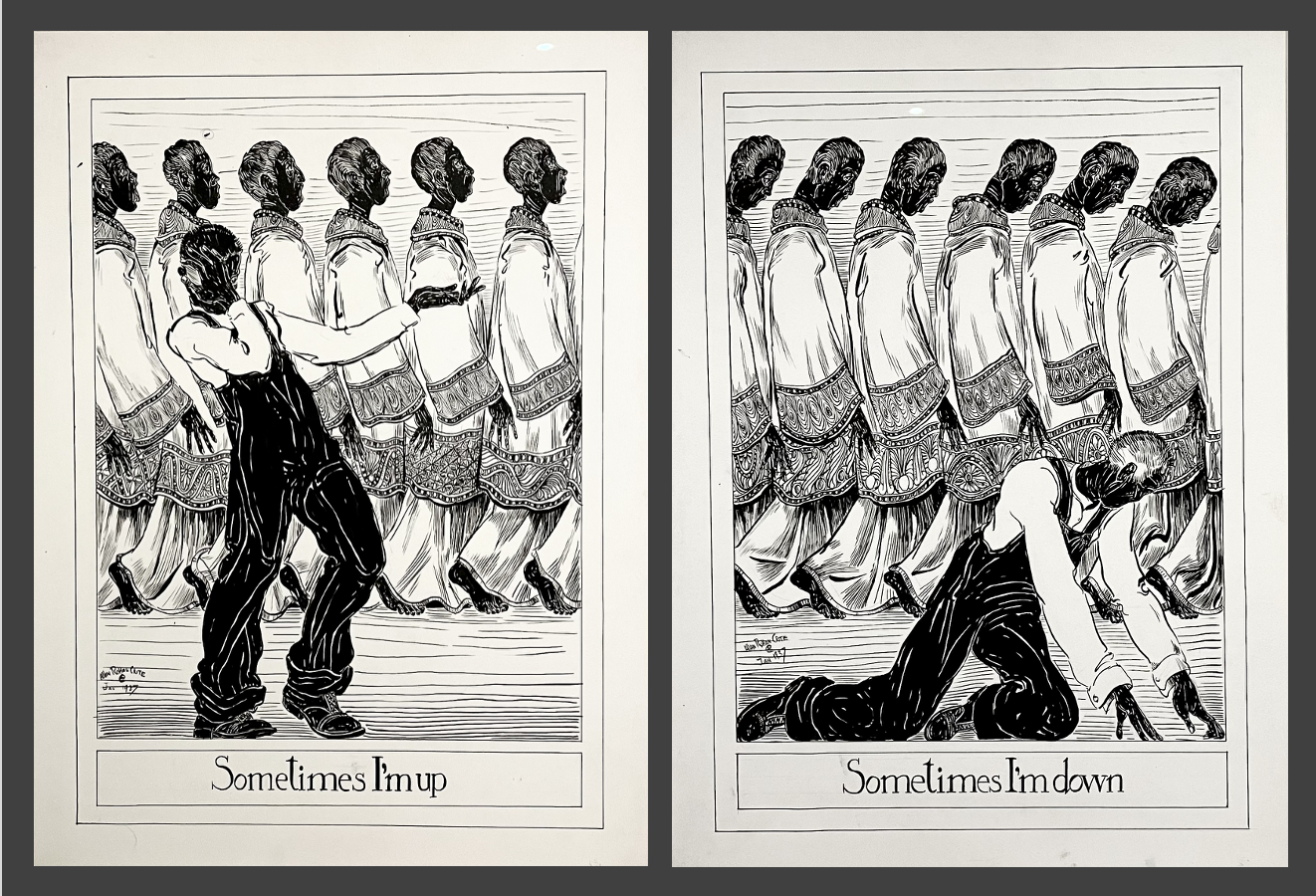

Three weeks later and I’m almost fully healed. My ribs still hurt when I lie down to sleep and when I rise in the morning, but sitting and walking are fine. In another week I’ll be able to return to the gym and attempt some light weightlifting, a welcome resumption of my weekly routine. There was, however, a silver lining to my accident. In the days immediately following it, I could do little else but read. Sitting down in a chair, I was stuck there. So it was that I took A River Runs Through It (1976) by Norman Maclean off the bookshelf in my father’s office and began to turn its pages. Allan Rohan Crite. Sometimes I’m Up, Sometimes I’m Down. Illustration for Three Spirituals from Earth to Heaven (Cambridge, Mass., 1948),” 1937.

Allan Rohan Crite. Sometimes I’m Up, Sometimes I’m Down. Illustration for Three Spirituals from Earth to Heaven (Cambridge, Mass., 1948),” 1937.

Did you ever read Ambrose Bierce’s short story “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge”? If not, it starts as the story of a man who is going to be hanged. As the trap door opens under him, he falls, the rope tightens around his neck but snaps instead of bearing his weight, and he is able to escape from under the gallows. For several pages he wanders through a forest truly sensing the fullness of life in himself and around himself for the first time.

Did you ever read Ambrose Bierce’s short story “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge”? If not, it starts as the story of a man who is going to be hanged. As the trap door opens under him, he falls, the rope tightens around his neck but snaps instead of bearing his weight, and he is able to escape from under the gallows. For several pages he wanders through a forest truly sensing the fullness of life in himself and around himself for the first time.

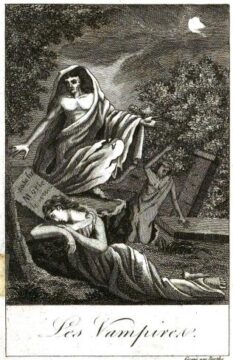

Most fiction tells the story of an outsider—that’s what makes the novel the genre of modernity. But Dracula stands out by giving us a displaced, maladjusted title character with whom it’s impossible to empathize. Think Anna Karenina, Madame Bovary, or Jane Eyre but with Anna, Emma, or Jane spending most of her time offstage, her inner world out of reach, her motivations opaque. Stoker pieces his plot together from diary entries, letters, telegrams, newspaper clippings, even excerpts from a ship’s log. Everyone involved in hunting down the vampire, regardless of how minor or peripheral, has their say. But the voice of the vampire himself is almost absent.

Most fiction tells the story of an outsider—that’s what makes the novel the genre of modernity. But Dracula stands out by giving us a displaced, maladjusted title character with whom it’s impossible to empathize. Think Anna Karenina, Madame Bovary, or Jane Eyre but with Anna, Emma, or Jane spending most of her time offstage, her inner world out of reach, her motivations opaque. Stoker pieces his plot together from diary entries, letters, telegrams, newspaper clippings, even excerpts from a ship’s log. Everyone involved in hunting down the vampire, regardless of how minor or peripheral, has their say. But the voice of the vampire himself is almost absent.