by Tim Sommers

In “Calculating God,” Robert J. Sawyer’s first-contact novel, the aliens who arrive on Earth believe in the existence of God – without being particularly religious. Why?

There are certain physical forces, they explain, that make life in our universe possible only if they are tuned to very specific values. Which they are. We are here, after all. But there’s no physical reason that the values need to be set the way they are. The aliens have concluded that someone, or something, set the values of these parameters at the beginning of the universe to insure that life would come into existence. That something they call God.

Here’s a much earlier, very different version of this argument. If you were hiking through the woods and you picked up a shiny object that turned out to be a small stone, it would probably not occur to you that it might have been made by someone. If it turned out to be a watch, however, you would immediately conclude that it had been intentionally created. So, is the universe more like a stone or a watch?

This argument from design was an especially powerful argument for the existence of God when very little was known about biology. The complexity of living things puts watches to shame. But then Darwin came along and used evolution to explain how such diversity, complexity, and apparent design could come about without a designer.

Just when the argument that the complexity of our world could only be explained by God seemed lost, a new, purely physical reason to think that the universe was designed appeared. The one the aliens embrace.

“A striking phenomenon uncovered by contemporary physics,” Kenneth Boyce and Philip Swenson write in their forthcoming paper “The Fine-Tuning Argument Against the Multiverse,” (Philosophy Quarterly) is that many of the fundamental constants of nature appear to have arbitrary values that happen to fall within extremely narrow life-permitting windows.”

As a non-physicist, even trying to give an accurate example of a fine-tuned constant that I could pretend to understand has been difficult. I decided it might be best to fully outsource it. Here’s an example from philosopher (and physics Ph.D.), Simon Friederich, in the reliably reliable, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

“The strength of gravity, when measured against the strength of electromagnetism, seems fine-tuned for life. If gravity had been absent or substantially weaker, galaxies, stars and planets would not have formed in the first place. Had it been only slightly weaker (and/or electromagnetism slightly stronger), main sequence stars such as the sun would have been significantly colder and would not explode in supernovae, which are the main source of many heavier elements. If, in contrast, gravity had been slightly stronger, stars would have formed from smaller amounts of material, which would have meant that, inasmuch as still stable, they would have been much smaller and more short-lived.”

Friederich, like Boyce and Swenson, cites five fine-tuned constants, though some sources point to as many as 30 – and Friederich raises the possibility that the initial conditions of the universe, and some physical laws, might also be considered fine-tuned for life. Is God the right explanation for such pervasive fine-tuning?

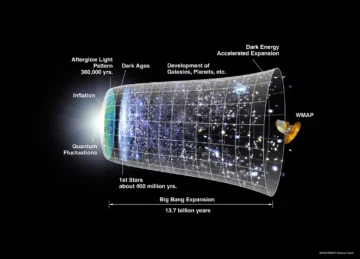

Evolution may come to the rescue again. Not biological evolution, but physical evolution this time. There are reasons to believe that our universe is part of a multiverse. Many (most?) physicists believe that this universe is one of a very large, maybe even infinite, number of universes. There are different theories about why and how there are so many universes, Max Tegmark argues for a multiverse with four levels – and Brian Greene argues for nine types of multiverses. But the view that we live in some sort of multiverse is ubiquitous.

For simplicity, let’s just say that somehow, our universe is just one of a very large number of universes. Here’s an explanation for fine-tuning, then. There are many universes where the relevant constants are set at different values. Only where they are set just right, around here, for example, does life arise. Only where life arises will intelligent life arise to ask the question, ‘Why are the values of these constants just-so?’ The only answer being, not that we were “put” into such a universe, but because we are in the only kind of universe that we could be in (or one of the set of kinds of universes that we could be in). That’s called the anthropic principle.

Compare, Douglas Adams’s sentient puddle that says, “This is an interesting world I find myself in — an interesting hole I find myself in — fits me rather neatly, doesn’t it? In fact, it fits me so staggeringly well, it must have been made to have me in it!”

We are not lucky to be in a universe made for us, on this view. We are, necessarily, in a universe that we could be in.

Here’s how Boyce and Swenson attempt to turn the tables in this debate. They say, it’s not that our universe being fine-tuned for life is explained by the multiverse. We don’t know that there is a multiverse, and fine-tuning is not, in and of itself, evidence for a multiverse. Rather, the fine-tuning of our universe makes it both more likely that there is a God – and less likely that there is a multiverse.

They use formal Bayesian inferences to make the argument. I am going to assume we can get the gist of it without all the machinery, though the devil, or in this case, maybe, God, is in the details – and those you can find here. They argue:

(1) The likelihood that our universe is finely-tuned and that there is a God is greater than the likelihood that the universe is finely-tuned and that there is no God.

That is essentially, the fine-tuning argument. Fine-tuning increases the likelihood that God exists. We’ll assume that this is true.

(2) If there is no God, then the likelihood that our universe, in particular, is finely tuned is still independent of whether a multiverse exists.

In other words, Boyce and Swenson assume (following Hacking and White) that fine-tuning is not, in and of itself, evidence for a multiverse.*

Here’s the reasoning.

The more you roll a pair of dice, the more likely it is that one of your rolls will be (the otherwise unlikely) double-sixes (1/36). But somebody rolling a double-six is not evidence that they’ve had many prior rolls. The probability of rolling double-sixes on any given roll is independent of the number of rolls. So, even if we believe that the fact that there are a large number of universes makes it more likely that some of these are fine-tuned for life, our universe being fine-tuned is not evidence that there are many universes – any more than double-sixes are evidence of a large number of rolls.

(3) If you assume there is a God, then the likelihood that this universe would be fine-tuned is greater if this is the only universe, than it is if there is a God and there are also many other untuned universes.

If we grant that various background beliefs suggest God is not a life-maximizer, (“the vast majority of regions of our universe are hostile to life,” for example, as Boyce and Swenson say), but God wants there to be some life; if this is the only universe, for there to be life, God would have to fine-tune this one.

God is more likely to fine-tune for life in this universe (which as far as we know is the only one), if it is, in fact the case, that it is the only one, than if there are many others. The punchline is that since this universe is finely-tuned, it’s actually less likely that there are other untuned universes.

I am not sure. Here’s my analogy.

Suppose you believe your mom wanted to write a great philosophy book before she died. Now, she has died and you are going through her personal papers and find a manuscript that you believe (correctly) is a great philosophy book. Should you stop now on the assumption that it is more likely that she only wrote one great philosophy book and you have found it. Or should you keeping going on the assumption that if she wrote one it is now more likely she wrote others.

Boyce and Swenson were kind enough to offer me tons of feedback on this paper (all the mistakes are still mine, of course). So, here’s Boyce’s reworking of the analogy in full.

“You know your mom was committed to writing at least one great philosophy book in the time she had remaining to her. You also suspect she other literary ambitions (such as writing a science fiction novel) that were of lower priority to her (so that she likely would write the philosophy book first and only that if that’s all she had time for). You know that these literary ambitions came to her later in life (before that she was too occupied with her career as a geologist) but are not sure just how late. You find a manuscript of hers (not knowing whether there are any others) an open it to find it is a philosophy manuscript. At that point, I say you get evidence that she acquired her literary ambitions later rather than earlier. Of course, you should keep looking for that science fiction novel, but your hope of finding it should decrease. It is more likely she did not have time to write it. On the other hand, had you discovered that the manuscript was a science fiction novel, you should be confident that the philosophy manuscript is around somewhere.”

If you know her time was quite limited and that she prioritized writing philosophy over science fiction, it is still the case that you have more reason to think the science fiction is there somewhere, I would argue, because if she could write one book, she could have written the other. But since the two books are competing against each other (time-wise), I read Boyce as saying, finding the one she prioritized makes, in fact, makes it less likely that the other exists. It may come down to which background facts you emphasize.

So, I guess here is where I might press one objection. Remember, (2) above? “If there is no God, then the likelihood that our universe, in particular, is finely tuned is still independent of whether a multiverse exists.” Doesn’t that cut both ways? If there is a God, then the likelihood that our universe, in particular, is finely tuned is still independent of whether the multiverse exists. Doesn’t the background assumption that God is not a life-maximizer underline the possibility that God also created lots of lifeless, untuned universes as well as this one?

To my mind, Boyce and Swenson have come to a significant conclusion (beyond the Hacking/White thesis) with just this – that fine-tuning is not evidence for the multiverse. But I’m not sure yet that they have evidence against the multiverse.

Boyce in correspondence wrote that “It can go both ways. It is formally consistent to say that the evidence from fine-tuning raises the probability of the hypothesis that God fine-tuned a whole bunch of universes while also lowering the probability that God made more than one universe.”

“It could go like this: Discovering that this universe is fine-tuned could make it more likely it is the only universe there is via the reasoning Swenson and I provide. So that evidence ends up decreasing the probability of the multiverse hypothesis overall.”

“Even so, the same evidence may increase the probability of certain specific versions of the multiverse hypothesis, e.g., it is more likely that God fine-tuned this universe on the assumption that there is a multiverse and God fine-tuned all of the universes in it than it is on the assumption that there is a multiverse and God only fine-tuned some of them.

“So, the fact that this universe is fine-tuned raises the probability of the version of the multiverse hypothesis according to which God fine-tuned all the universes there are while lowering the probability of the version of the multiverse hypothesis according to which God fine-tuned only some of the universes there are.”

Swenson helpfully put the argument like this. There are four possibilities: (i) There is a God and a multiverse, (ii) There is a God and only one universe, (iii) There is no God and there is a multiverse, and (iv) There is no God and only one universe.

If (iv) there is no God and only one universe, then it’s surprising that this one universe is somehow fine-tuned. If (i) there is a God and a multiverse, and we assume that God doesn’t fine-tune every universe, it’s surprising that this one is tuned. If (iii) there is no God and there is a multiverse, it’s (again) surprising that this universe is one of the fine-tuned ones. Finally, only (ii) is it not surprising. That there is a God and only one universe, in other words, is more likely than the alternatives.

That is the argument as I understand it and I will leave the authors with the last word.

________________________

*Boyce defends the Hacking/White argument against some objections here. You can also find the relevant references to Hacking and White in the bibliography of that paper. Finally, and most importantly, thanks to Phil Swenson and Ken Boyce for indulging me by reading and commenting on multiple drafts. I am sure I still don’t have this exactly right, but that truly is my fault and not theirs. Thanks to both.