by Claire Chambers

Having begun Hindi and eventually reaching an intermediate level, I sailed into the vast ocean of the Urdu language. There, a novice again, I felt lost amid roiling currents. Yet I kept my compass pointed towards receptivity, hoping the winds of curiosity would steer me to the shores of understanding. I’m not there yet, so join me in my voyage.

Having begun Hindi and eventually reaching an intermediate level, I sailed into the vast ocean of the Urdu language. There, a novice again, I felt lost amid roiling currents. Yet I kept my compass pointed towards receptivity, hoping the winds of curiosity would steer me to the shores of understanding. I’m not there yet, so join me in my voyage.

As Liz Chatterjee wryly notes, ‘It is obligatory to point out that Urdu is a cognate of “horde” and its name came from the Muslim occupiers’ ordu, camp’. This is because the language developed among the armies of the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughal Empire, whose soldiers used a mixture of Indian languages and Persian as a lingua franca. Over time, this melange of languages came to be known as Urdu, and the Perso-Arabic script was used to write it.

Leaping forward a century or two, the Partition of 1947 was a traumatic event that left many Urdu-speaking people feeling alienated and excluded from the new Indian society. Partition has caused a shift in the perception of Urdu, which has been reduced to a language spoken primarily by the elderly and by Muslim minorities in India. After Partition, Urdu became the national language of Pakistan, while Hindi was India’s official language (soon joined by English). Despite this, Urdu continued to be spoken by millions of people in India, and it is still one of the 22 scheduled languages of India. In the decades following Partition, however, the use of Urdu in India declined due to a variety of political, social, and economic factors. Many people who spoke Urdu as their first language began to switch to Hindi, and the use of Urdu in education, films, and government business also languished. Today, Urdu remains an important language in India, but it is not as widely spoken as it once was.

In Anita Desai’s novel In Custody, she portrays post-Independence Urdu suffering decline and neglect in India. The narrative’s protagonist, Deven, is a schoolteacher who is passionate about Urdu poetry and literature, but he finds himself in a society that is largely indifferent to the language. Deven is increasingly frustrated by the lack of appreciation for Urdu and the fact that it is no longer a language of importance or prestige in India. He is saddened to see the language and its literature fading away, and his attempts to challenge the status quo are met with resistance.

In Anita Desai’s novel In Custody, she portrays post-Independence Urdu suffering decline and neglect in India. The narrative’s protagonist, Deven, is a schoolteacher who is passionate about Urdu poetry and literature, but he finds himself in a society that is largely indifferent to the language. Deven is increasingly frustrated by the lack of appreciation for Urdu and the fact that it is no longer a language of importance or prestige in India. He is saddened to see the language and its literature fading away, and his attempts to challenge the status quo are met with resistance.

In today’s real world, too, there are some depressing language politics on both sides of the border, with purists trying to drive a wedge between Hindi and Urdu. What’s more, in Pakistan the Urdu leans more towards Arabic, whereas Indian Urdu uses a larger number of Persian and Sanskrit words. So Indian Urdu and Pakistani Urdu, too, have gone in different directions over the past 75 years.

Writing of Partition, Salman Rushdie uses a cutting metaphor: ‘the borderline created by partition had cut through the landmass of south Asia as a taut wire cuts through a cheese, literally slicing Pakistan away from the landmass of India, so that it could slowly float away across the Arabian Sea’. But in his 1988 novel The Shadow Lines Amitav Ghosh argues that rather than ‘the two bits of land … sail[ing] away from each other like the shifting tectonic plates of the prehistoric Gondwanaland’, politicians on both sides of the border discover an irony. ‘There had never been a moment in the four-thousand-year-old history of that map’, he writes, when India and Pakistan ‘were more closely bound to each other than after they had drawn their lines’. My voyage is about trying to bind together the two plates of Gondwanaland rather than seeing them float off in different directions.

Hindi and Urdu should not be viewed as two separate languages, because they are actually sister tongues. The language spoken in many parts of north India is Hindustani, a product of the syncretic culture of the Ganga-Jamuni region. If you aren’t aware of this intermixing, here is an Anglophone analogy. Imagine an American is talking to a Glaswegian. Their accents would differ wildly, their lexicons somewhat, and they’d doubtless have a few misunderstandings. Ultimately, though, they would be able to communicate and have a pretty complex conversation. If they wanted to follow up their chat with an email exchange, though, this is where the analogy gets interesting: they wouldn’t be able to read each other’s writing.

because they are actually sister tongues. The language spoken in many parts of north India is Hindustani, a product of the syncretic culture of the Ganga-Jamuni region. If you aren’t aware of this intermixing, here is an Anglophone analogy. Imagine an American is talking to a Glaswegian. Their accents would differ wildly, their lexicons somewhat, and they’d doubtless have a few misunderstandings. Ultimately, though, they would be able to communicate and have a pretty complex conversation. If they wanted to follow up their chat with an email exchange, though, this is where the analogy gets interesting: they wouldn’t be able to read each other’s writing.

I learned from Delhi’s Zabaan School for Languages that one of the benefits of having Hindi as a language and then learning Urdu is that you know a good 90 percent of the new language already. The grammar is the same (aside from the compound -e- construction known as izafat in Urdu). For the new words you just need to use a dictionary, and each time you do this you’re learning something new. Working on Urdu is only going to enrich your Hindi and vice versa.

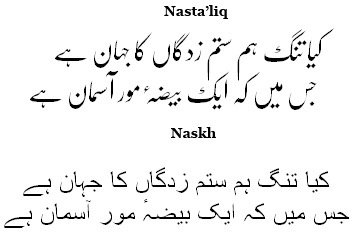

The main differences between the two languages lie in their higher-register vocabulary and – most strikingly – in the scripts used to write them. Hindi is written in the left-to-right Devanagari script. The language is associated with Hindus, and uses a large amount of vocabulary borrowed from Sanskrit. Urdu, on the other hand, deploys a version of the right-to-left Perso-Arabic script called Nastaliq. These days it is predominantly, but not solely, a Muslim language, and its technical diction often derives from Persian and Arabic.

The script doesn’t go straight across the page along a horizontal line, but instead an eye-catching feature is that it slopes downwards. Indeed, ‘Nastaliq’ means the falling script, which is a lyrical detail. Although Nastaliq is the gold standard in Pakistan (and is also used for Persian), BBC Urdu made the controversial choice of opting for a non-falling version of the script, Naskh, which is commonly used in many Arab countries. While it is not as easy on the eye as swooning Nastaliq, in the infancy of my Urdu competence I much prefer Naskh. At least this typeface makes it clearer where words begin and end.

The script doesn’t go straight across the page along a horizontal line, but instead an eye-catching feature is that it slopes downwards. Indeed, ‘Nastaliq’ means the falling script, which is a lyrical detail. Although Nastaliq is the gold standard in Pakistan (and is also used for Persian), BBC Urdu made the controversial choice of opting for a non-falling version of the script, Naskh, which is commonly used in many Arab countries. While it is not as easy on the eye as swooning Nastaliq, in the infancy of my Urdu competence I much prefer Naskh. At least this typeface makes it clearer where words begin and end.

Both Nastaliq and Naskh are famously difficult to learn because you can’t spell out words completely the way you do in phonetic Devanagari. Some of the information is missing, namely the short vowels. A consonant can have three implied vowels, a, i, or u. Your brain has to select which one is appropriate. This complication is what Urdu is notorious for, but try not to feel daunted. Think of it as being lk txt spk, rdng wth nly cnsnts: whch w cn d, bcs w rcgnz wrds s whl shps. This is trickier when you’re faced with a word from Urdu that isn’t familiar in Hindi, and such situations are where you become a true language learner. Urdu does includes a number of diacritical marks, some of them indicating what vowel to use. However, all too often (except in some children’s books), these diacritics are dispensed with. So the bad news is the implied vowel, but over time it comes to seem not that bad.

Urdu has all the letters – including ژ, pronounced something like the ‘g’ in rouge or the ‘zh’ in pleasure. This alphabet only appears in a handful of Urdu words and its pronunciation in fact varies in each! Another complication is that without going deeply into it, there are two groups of letters: joiners and the non-joiners or breakers. The word Urdu itself is made up solely of aloof non-joiners/breakers: اردو, which becomes a neat way of teaching ا (alif) and و (wao), as well as the ر (re) and د (dal) letter groups. But it’s the gregarious joiners you have to watch, as they often look quite different depending on whether they come at the beginning, in the middle, or at the end of words. This means it can feel as though there are far more than the 39 letters in this alphabet. That said, for me learning a new script has been a bit like having a baby. The first time, with Devanagari, I had no belief I had the tenacity or talent to push this thing out. But with the neglected second child of Urdu, I gritted my teeth and got on with it, knowing that all things are possible.

For Maan in Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy, learning Urdu is a way to seduce the singer Saeeda Bai via romantic ghazal poetry and extravagant love letters. Yet the young swain finds himself endlessly practising basic letters. Even amid this rote learning, sex isn’t far from Maan’s mind, as the character م (meem) reminds him of ‘a curved spermatozoon’. For my part, ن (noon) has always reminded me of a bare breast. Maan and I apologize for sullying your chaste Urdu! When he complains about being stuck at first base with the alphabet, Maan’s teacher tells him that jumping straight into ghazals ‘would be like teaching a baby to run the marathon’. Maan chafes against his tutor’s restrictions, deciding that the Urdu alphabet ‘was difficult, multiform, fussy, elusive, unlike either the solid Hindi or the solid English script’. Maan’s struggle to master the language and appreciate the beauty of its calligraphy makes me laugh and wince, so similar as it is to my early frustrations.

For Maan in Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy, learning Urdu is a way to seduce the singer Saeeda Bai via romantic ghazal poetry and extravagant love letters. Yet the young swain finds himself endlessly practising basic letters. Even amid this rote learning, sex isn’t far from Maan’s mind, as the character م (meem) reminds him of ‘a curved spermatozoon’. For my part, ن (noon) has always reminded me of a bare breast. Maan and I apologize for sullying your chaste Urdu! When he complains about being stuck at first base with the alphabet, Maan’s teacher tells him that jumping straight into ghazals ‘would be like teaching a baby to run the marathon’. Maan chafes against his tutor’s restrictions, deciding that the Urdu alphabet ‘was difficult, multiform, fussy, elusive, unlike either the solid Hindi or the solid English script’. Maan’s struggle to master the language and appreciate the beauty of its calligraphy makes me laugh and wince, so similar as it is to my early frustrations.

One thing that helped me break through to functional literacy was a series of group lessons given by Abhishek Shukla. Abhishek is from a Hindu background and is a respected Urdu-language poet from Lucknow who offers these language classes online. Using a simple blackboard he teaches the tricky Nastaliq script through the Hindi medium, making it easier for Hindi-wallahs to learn Urdu. As the sole non-Indian my batch, I joined the class with jangling nerves. However, Abhishek’s passion for both Hindi and Urdu, as well as his lively sense of humour, make his classes unforgettable and very enabling for his students.

One thing that helped me break through to functional literacy was a series of group lessons given by Abhishek Shukla. Abhishek is from a Hindu background and is a respected Urdu-language poet from Lucknow who offers these language classes online. Using a simple blackboard he teaches the tricky Nastaliq script through the Hindi medium, making it easier for Hindi-wallahs to learn Urdu. As the sole non-Indian my batch, I joined the class with jangling nerves. However, Abhishek’s passion for both Hindi and Urdu, as well as his lively sense of humour, make his classes unforgettable and very enabling for his students.

Abhishek believes that language connects people and he expresses pride that international students have joined his classes and ‘started their journey with this beautiful language’. He has now designed an Urdu poetry appreciation course for those like the fictional Maan who are attracted to high-quality verse. In this course, students get to know about the Urdu poetic tradition in India, the evolution of the language, and the structure of prosody. The classes are focused on ghazal writing and its different aspects. So far about 100 people have learned to read and write Urdu with him. The poet plans to continue teaching Urdu, and is thrilled with the response he has received. Abhishek says, ‘I feel that I have served the purpose well and I will be continuing with Urdu, teaching classes’.

People often remark upon the politeness of Urdu, especially when they think of the courtly manners of old Bollywood. That inbuilt ‘please’ of the polite imperative is present in Hindi too, but Urdu takes it to new levels. What’s more, in Urdu as with Hindi, there are two main words for you: tum and aap, which are similar to the French tu/vous. The Hindustani language has so developed within certain parts of India that specific regions will indiscriminately refer to everyone as aap, while others will reserve the right to the more informal ‘tum’. Similarly, in much of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, for example, the first-person plural pronoun hum (we) gets deployed to talk about oneself. It’s like the royal we of Queen Victoria: ‘We are not amused’. And I wonder whether, and how much of an impact, cultural practices within particular states had on the development of these patterns.

Urdu takes it to new levels. What’s more, in Urdu as with Hindi, there are two main words for you: tum and aap, which are similar to the French tu/vous. The Hindustani language has so developed within certain parts of India that specific regions will indiscriminately refer to everyone as aap, while others will reserve the right to the more informal ‘tum’. Similarly, in much of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, for example, the first-person plural pronoun hum (we) gets deployed to talk about oneself. It’s like the royal we of Queen Victoria: ‘We are not amused’. And I wonder whether, and how much of an impact, cultural practices within particular states had on the development of these patterns.

In Kamila Shamsie’s 2017 novel Home Fire, the Westernized character Ayman (whose name is celticized to Eamonn), defines the Urdu word bay-takalufi as ‘informality as an expression of intimacy’. His conversational partner Isma corrects him:

‘I wouldn’t say intimacy. It’s about feeling comfortable with someone. Comfortable enough to forget good table manners. If done right, it’s a sort of honour you confer on the other person when you feel able to be that comfortable with them, particularly if you haven’t known them that long.’

This is a familiar concept to me. Reena, the best friend I grew up with in Leeds, taught me to throw most kinds of manners including table ones out the window early on in our 30-year relationship. Still, I know I sometimes offend subcontinental hosts with the difficulty I have dispensing with insincere British ‘thank yous’ and ‘pleases’. They think I am not conferring that honour of bay-takalufi on them, and that I’m being impolitely polite and formal.

Urdu has a prevalent and complex system of honorifics and can capture the specificities of your relationships with family members. Yet there is only one word for tomorrow and yesterday, kal, which you understand contextually by the use of the past or the future tense. This accurately signals a certain vagueness around time-keeping in South Asia.

It took some time to get used to reading and doing digital writing in the Urdu script. That said, I found that my prior knowledge of Hindi helped me move forward with more confidence as I had quite a lot of vocabulary and grammar as a foundation. By now I can read simple Urdu, but more than twenty minutes or so and I start flagging as it still involves so much concentration. As for writing, I’ve been shying away from learning to write by hand. I can use the computer to construct emails and short documents. I feel it might be an unnecessary use of my brain’s hard drive to learn Urdu calligraphy when I have no one in the family to produce little notes for! But several friends have urged me to reconsider, as they say that mastering handwriting gives you a different and more intimate relationship with the language. Leanne Ogasawara told me that studying ‘calligraphy and writing and reading in Japanese were the real keys to the kingdom. There is a great book called Kingdom of Characters about Chinese that I am currently reading. And have you read Silvia Ferrara’s book on world scripts? The book has an unusual writing style that the translator must have worked hard to get right. She also has a wonderful approach to the way these writing systems originated’.

It took some time to get used to reading and doing digital writing in the Urdu script. That said, I found that my prior knowledge of Hindi helped me move forward with more confidence as I had quite a lot of vocabulary and grammar as a foundation. By now I can read simple Urdu, but more than twenty minutes or so and I start flagging as it still involves so much concentration. As for writing, I’ve been shying away from learning to write by hand. I can use the computer to construct emails and short documents. I feel it might be an unnecessary use of my brain’s hard drive to learn Urdu calligraphy when I have no one in the family to produce little notes for! But several friends have urged me to reconsider, as they say that mastering handwriting gives you a different and more intimate relationship with the language. Leanne Ogasawara told me that studying ‘calligraphy and writing and reading in Japanese were the real keys to the kingdom. There is a great book called Kingdom of Characters about Chinese that I am currently reading. And have you read Silvia Ferrara’s book on world scripts? The book has an unusual writing style that the translator must have worked hard to get right. She also has a wonderful approach to the way these writing systems originated’.

I kick myself for not learning Urdu in my late teens or early twenties and instead putting it off for years. However, I also have some sympathy with my younger self, since there’s not as much of a textbook or online infrastructure as exists for Hindi and according to most learners Nastaliq is a harder script to master properly than Devanagari.

When my Hindi teacher went on maternity leave from June 2022, it seemed like the right time to embark on the voyage. As a complete beginner I worked my way through the Rasm-ul-Khat course at Aamozish.com and endlessly practised just the first four letter lessons from the Arabic course on Duolingo.

This was helpful, but I wish there were more free resources out there as there are with Hindi. Mondly is an app for playing on your phone a few minutes every day instead of doomscrolling through news sites or social media. Full of minor errors as it is, Ling’s fun gamification nonetheless makes its small fee a price worth paying. But the most valuable resource is my private teacher Yusuf Mallu from Rajasthan. He knows both Hindi and Urdu, is insatiably interested in etymology and connotations, and his classes on Italki are fun and inexpensive. Best of all from a gup-shup perspective, he was the first disabled contestant to appear on India’s Who Wants to be a Millionaire, Kaun Banega Crorepati, back in 2011 (he won a not-too-shabby ₹125,000).

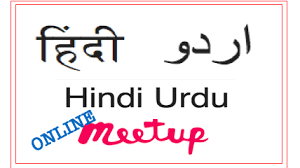

Every Monday evening, I attend a Meetup.com group dedicated to Hindustani. The group comprises members who are interested in either Hindi, Urdu, or both. It is refreshing to converse with mostly non-native but fluent speakers who speak more slowly, use less slang, and have familiar accents. Our conversations, mostly in Hindustani, revolve around the language itself. These sessions should not be seen as formal classes, though sometimes we are assigned a simple task to complete beforehand, like watching a short film on YouTube. We’re not supposed to discuss politics or religion, although sometimes we can’t help ourselves! A little intimidated at first, I now feel fortunate to have discovered this group, and they have welcomed me with great openness. While the discussions are probably best suited for intermediate and advanced learners, people of all levels are warmly encouraged to participate. Several of the people in this group have become proper friends, and the conversations are fascinating.

Every Monday evening, I attend a Meetup.com group dedicated to Hindustani. The group comprises members who are interested in either Hindi, Urdu, or both. It is refreshing to converse with mostly non-native but fluent speakers who speak more slowly, use less slang, and have familiar accents. Our conversations, mostly in Hindustani, revolve around the language itself. These sessions should not be seen as formal classes, though sometimes we are assigned a simple task to complete beforehand, like watching a short film on YouTube. We’re not supposed to discuss politics or religion, although sometimes we can’t help ourselves! A little intimidated at first, I now feel fortunate to have discovered this group, and they have welcomed me with great openness. While the discussions are probably best suited for intermediate and advanced learners, people of all levels are warmly encouraged to participate. Several of the people in this group have become proper friends, and the conversations are fascinating.

My journey into the world of Urdu has been an arduous but bracingly adventurous voyage. Through choppy waters, I have come to appreciate the sheer oceanic joy of this language. Though I still fear I’m never going to come close to the shore.