by Scott Samuelson

Though I’m at best a mediocre tennis player, I’ve achieved something in the sport that the pros achieve only at their finest, which I’ve taken to calling “tennisosity,” a hybrid of “tennis” and “virtuosity.” I coined the term several years ago, in the sweaty aftermath of a match in which my opponent and I had entered into its state. Among my friends and family, the ugly term tennisosity has stuck—I suspect because it describes something vitally yet elusively important, something with an ethical and an aesthetic dimension that can apply to any meaningful human activity.

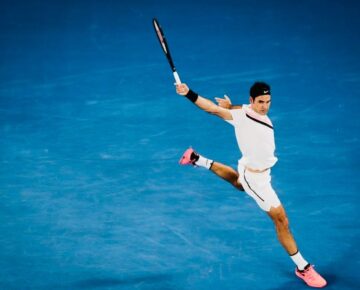

Tennisosity (in the realm of tennis) is when you and your opponent are so well-matched that the competition not only raises both of your play to a higher level but perfectly realizes the game of tennis. The way I put it to my exhausted opponent was, “We just played the 2008 Wimbledon Final”—the battle between Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal, sometimes called the greatest match ever, where Nadal won his first Wimbledon against the defending champ (Federer had won the previous five straight, including the last two against Nadal). Even though neither my opponent nor I could return the serve of your average high school varsity tennis player, our rallies were just as dramatic as Federer’s and Nadal’s, each of us got to just as many shots that the other didn’t think could be gotten to, our aces were just as glorious, and our double faults were just as tragic—at least within the context of our game.

I admit that my backhand isn’t at the level of Roger Federer’s! I’m giggling at even drawing the comparison. By the normal metrics and standards of excellence in tennis, everything about my game is junk. Also, there was no public recognition riding on my match—not even the chintzy trophy of a local tournament, much less the engraved silver of the most storied competition in tennis. In fact, nobody was watching.

And yet, had others been watching us, I believe that their aesthetic experience of our tennis match would have been similar in kind to the great Wimbledon Final—obviously not concerning our individual skillsets but concerning what the interactive combination of our skillsets involved. My opponent and I had to dig deep again and again. The same kind of grit and imagination Federer and Nadal had to draw on, we had to draw on. The glory of tennis was on display for all to see—even though nobody happened to be there to see it. If I remember right, one of us cried.

When a master is cleaning a lesser player’s clock, though the superb skills and shots can be oohed and ahhed over, the match as a tennis match soon gets boring. Even the competition of two great players becomes tedious when one of them is a little off their game. When you keep watching them play, it’s either in the hopes that the match will heat up or because you have money riding on it. Whereas when two evenly-matched players of any level are simultaneously pushing each other’s limits, it’s extremely exciting to watch—in exactly the way that a tennis match is supposed to be exciting.

Obviously, it’s especially beautiful if the individual play wows you and the match is great. And it’s historically beautiful—in the way of the 2008 Wimbledon Final—when the individual play wows you, the match is great, and a major trophy is riding on it. But achieving tennisosity can be done at any level above basic competence, for the point of tennis isn’t to hit serves above a certain speed or have a killer two-handed backhand or even to win a major title. The point is for a great game to be played, one that brings out the best in each player within the confines of the sport.

If (to take the kind of thing that fans like to fantasize about) William Renshaw with his little wooden racquet were teleported from the nineteenth century to play Novak Djokovic, he’d likely be trounced (though if Renshaw had grown up at the same time as Djokovic, who knows?). It’s conceivable—hard to imagine but possible—that a player teleported from a hundred years from now would trounce Djokovic with his mere graphene racquet. What makes players like Djokovic great depends on the level of their play relative to those around them (arguably, what has made Djokovic especially great was that he had to achieve tennisosity with Federer and Nadal).

My point is that tennisosity isn’t about your skill level on an absolute scale or even about your victories and achievements. Renshaw’s and Djokovic’s names are literally etched in tennis history, whereas mine is writ in Gatorade. They have stretched the game to new levels, whereas the only thing I’ve stretched to new levels is the waistband of my tennis shorts. Still, we’ve all known moments in the paradise of tennisosity.

Though it’s like Csikszentmihalyi’s well-known idea of flow (where you’re utterly absorbed in a challenging activity done for its own sake), tennisosity is more than just a psychological state. It pertains more to the good of the activity itself. It’s the kind of thing appreciable—even loveable—by anyone who cares about the activity.

Tennisosity can happen in most any meaningful activity. What’s magical is that a tennisosic performance retains the pressure of its energy against its form. When cooks are pushing their abilities against the limits of what’s in the kitchen, the food is more soulful than a dish phoned in by a Michelin-starred chef. When Ptolemy in the Almagest was making his discoveries about Earth and its relation to everything else in the universe, he was achieving a scientific tennisosity that still makes for exhilarating reading (parts of it anyway), even though we already know what he got brilliantly right and what he got spectacularly wrong. Young children, though their grammar and spelling skills are rudimentary, are capable of remarkable tennisosity when they write poems, probably because their linguistic abilities and imaginative powers are relentlessly tested and expanded by the unfamiliar world around them. By contrast, William Wordsworth, who found tennisosity in poem after poem for a few early years, spent decades recollecting emotion in tranquil verse without tennisosity, even though all his later work was accomplished and published.

Could it be that the best reason to admire the Nadals, Ptolemies, and young Wordsworths of the world is not really what they accomplish (which can be surpassed, refuted, or forgotten) but how richly they embody tennisosity?

Virtue or virtuosity is often understood as being at or above a certain accepted level of excellence. For instance, years and years of lessons and practice are necessary for someone to become a virtuoso musician. By contrast, any musician can achieve tennisosity in any phase of development. Often a jam session in a garage produces the most beautiful music in the whole universe. In fact, folk music, the blues, and rock and roll—if not all forms of musical performance—hinge on tennisosity.

Similarly, tennisosity can be achieved throughout all phases of our relationships, our intellectual life, our work, our play. Virtuosity can take years. Tennisosity has a chance of happening today.

Philosophers as different as Aristotle, Epicurus, and Epictetus agree that virtue is crucial for human flourishing. Maybe what they were getting at—or what they ought to have been getting at—is closer to tennisosity than what we mean by “virtue”?

Now that robots can handily beat grandmasters at chess and outperform students at writing term papers, and perhaps outstrip all of us at any number of things soon enough, should we conclude there’s no point in playing chess or writing papers or doing anything else? Or should we figure out ways that our tennisosity can be enhanced by this situation? What if sports and education more generally were focused not on getting a few of the most talented on the elite team but on striving to put everyone in a position to achieve tennisosity?

Though we can’t exactly will tennisosity into existence, we can open ourselves up to it and put ourselves into positions where it’s got a chance of happening. I’m simultaneously proud of and grateful for my moments of achieved tennisosity. A curious (and perhaps important) thing about the match that led me to coin the term is that I don’t remember which of us was Nadal that day and which was Federer.

***

Scott Samuelson holds a joint appointment at Iowa State University in Philosophy & Religious Studies and Extension & Outreach. He’s the author of three books: Rome as a Guide to the Good Life, Seven Ways of Looking at Pointless Suffering, and The Deepest Human Life—all published by the University of Chicago Press.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.