by TJ Price

It’s a few days before Christmas, but it doesn’t feel like it. The weather app I use has subtitled the forecast for the holiday with a cheeky “feels more like Spring than Christmas,” and the temperature is hovering around seventy degrees Fahrenheit. I’m visiting family down in Cape Fear, and my nephew, all of four years old, sits rapt and silent for approximately ten minutes before abruptly transforming into a firecracker of noise, babbling and shrieking, a whirligig that hurls itself at the legs of whoever happens to first verify his existence. I’m probably reading into it, but it looks for all the world to me like a sudden paroxysm of solipsistic terror—as if he has been seized by the irrational and intrusive thought that (despite the empirical evidence of nearby voices and bodies moving to and fro in the kitchen) he is feeling a kind of doubt in his own ability to adequately integrate with the rest of us.

I understand this feeling, I think. As a child, my family would bring me over to my grandmother’s house and conduct conversations that floated austerely over my head. Sometimes that height was intentional, positioned as such because they wanted it out of my reach, like the medicine they kept on the top shelf of the bathroom cabinet. Sometimes it was because they wanted to abstract complexity to the extent that it would befuddle me and discourage any continued questioning. (The joke was on them—more often than not, such behavior would only deepen my urge to decode those encryptions, even if it often led to frustratingly reductionist statements in the form of tautology like “because that’s just how it is.”) I felt the terror of being excluded then not because something secret held any kind of promise or hope, but rather signified the coming of a threat against which I was unable to prepare. If I could not have defenses mounted to face obvious menaces, how could I be on guard against proverbial Greeks bearing gifts?

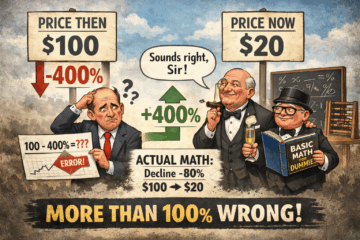

Oy. Where to start? Let me begin with a recent abuse involving percentages. Trump’s absurd claims about price declines of more than 100% have elicited a lot of well-deserved derision. How could someone with an undergraduate degree in business from Wharton make these mathematically impossible claims?

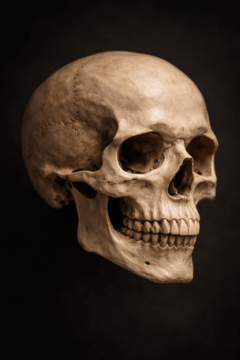

Oy. Where to start? Let me begin with a recent abuse involving percentages. Trump’s absurd claims about price declines of more than 100% have elicited a lot of well-deserved derision. How could someone with an undergraduate degree in business from Wharton make these mathematically impossible claims? In almost every medical school in the world, there is a cupboard—or a quiet back room—full of bones. The skulls are numbered, the femurs stacked like firewood, the ribs threaded onto metal wire. Officially, they are “teaching aids”. Unofficially, they are the remains of actual lives, reduced to objects that can be ordered from a catalogue.

In almost every medical school in the world, there is a cupboard—or a quiet back room—full of bones. The skulls are numbered, the femurs stacked like firewood, the ribs threaded onto metal wire. Officially, they are “teaching aids”. Unofficially, they are the remains of actual lives, reduced to objects that can be ordered from a catalogue. 2025 was a good year for books.

2025 was a good year for books.

“This is the mentality of our society. If someone is speaking English, he or she is really good, he or she is from a very good background,” one subaltern English learner tells the researchers in this study. “When someone speaks good English, Shah says, people assume that person is educated, knows how to carry himself, and is, crucially, ‘a good person’,” notes another.

“This is the mentality of our society. If someone is speaking English, he or she is really good, he or she is from a very good background,” one subaltern English learner tells the researchers in this study. “When someone speaks good English, Shah says, people assume that person is educated, knows how to carry himself, and is, crucially, ‘a good person’,” notes another.

Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,

The town had only one grocery store, and Steve wondered where the locals did their shopping. Certainly not here, but perhaps in a supermarket outside of town, one that required a car. Along with Julia, he picked up some Italian cheese, prosciutto, grapes, and a bottle of local wine, and they made their way up the hill to the house they’d rented for the week.

The town had only one grocery store, and Steve wondered where the locals did their shopping. Certainly not here, but perhaps in a supermarket outside of town, one that required a car. Along with Julia, he picked up some Italian cheese, prosciutto, grapes, and a bottle of local wine, and they made their way up the hill to the house they’d rented for the week.

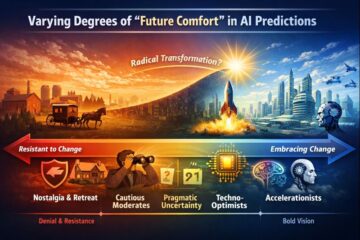

Back when I worked for large corporations, people would often talk of being in “period of change” or how they could “see the light at the end of the tunnel” after a period of heavy restructuring or similar. These days, you might be forgiven for wondering where the tunnel went. Change is incessant and showing no signs of slowing down. In fact, it is quite the opposite. We are entering a period when change might in fact actually be speeding up, even from its currently historically high levels. While not the majority view, nor the most likely scenario in my estimation, there is still a nonzero likelihood that we are in fact in the last few years of an era. Through the development of AGI – artificial general intelligence – the world could become unrecognizable in just a few years.

Back when I worked for large corporations, people would often talk of being in “period of change” or how they could “see the light at the end of the tunnel” after a period of heavy restructuring or similar. These days, you might be forgiven for wondering where the tunnel went. Change is incessant and showing no signs of slowing down. In fact, it is quite the opposite. We are entering a period when change might in fact actually be speeding up, even from its currently historically high levels. While not the majority view, nor the most likely scenario in my estimation, there is still a nonzero likelihood that we are in fact in the last few years of an era. Through the development of AGI – artificial general intelligence – the world could become unrecognizable in just a few years. Never before have I worried about rolling out of my bed or a chair and falling down, kerplunk! For no reason. Now I have to. I feel like a spacer on the first outer space mission, alert with every breath, having always to think about where to place each foot. constantly aware. As I walk, my legs sometimes shake. Sharp pangs wander erratically across my legs, occasionally intersecting with a joint, others centered around a muscle.

Never before have I worried about rolling out of my bed or a chair and falling down, kerplunk! For no reason. Now I have to. I feel like a spacer on the first outer space mission, alert with every breath, having always to think about where to place each foot. constantly aware. As I walk, my legs sometimes shake. Sharp pangs wander erratically across my legs, occasionally intersecting with a joint, others centered around a muscle. Marco A Castillo. Mangle I, 2025.

Marco A Castillo. Mangle I, 2025.