by Claire Chambers

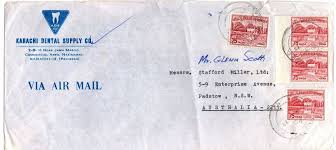

One day I went to my workplace in York, northern England, where I checked my pigeonhole as usual. An airmail letter lay in the metal box. Its postmarks were from Pakistan, and a man’s name and a Karachi address were scrawled on the back of the envelope. Because of the bimonthly columns I write for Dawn newspaper, I sometimes get email feedback. Occasionally people send me their books for review. But this slim package surprised me – especially when I broke the seal and pulled out four pages of Urdu handwriting.

One day I went to my workplace in York, northern England, where I checked my pigeonhole as usual. An airmail letter lay in the metal box. Its postmarks were from Pakistan, and a man’s name and a Karachi address were scrawled on the back of the envelope. Because of the bimonthly columns I write for Dawn newspaper, I sometimes get email feedback. Occasionally people send me their books for review. But this slim package surprised me – especially when I broke the seal and pulled out four pages of Urdu handwriting.

It had been years, probably over a decade, since I received a personal letter. My teenage sons and twenty-something Urdu teacher, Fareeha, claim they’ve never had one, apart from official dispatches. In this digital dunyā, what a privilege it is to get a letter, and that too a piece of mail which had travelled a long way.

This reaching out across distance and cultures reminded me of Saadat Hasan Manto’s ‘Letters to Uncle Sam’ – sharp, satirical notes dissecting international politics and American power. Balram’s letters to the Chinese Premier in The White Tiger also came to mind, with Aravind Adiga’s character telling Wen Jiabao about Indian corruption and inequality. My situation was different – I was in the UK, not the US or China – and the letter writer’s tone proved to be sincere rather than arch or ironic. Yet the impulse to communicate across borders felt equally urgent. In honour of Manto’s ‘Letters’ and to protect my correspondent’s anonymity, in this blog post I will call him Sami. I surmise, though, that he is much closer to my nephew’s age than my uncle’s.

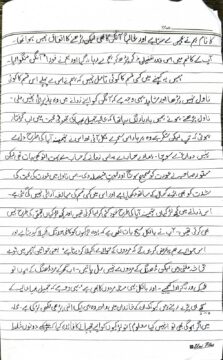

I gazed at the pages, drawn in by the Urdu script and feeling enchanted that someone had created these words with such dexterity. I exulted even more at the newfound reading skills which allowed me to decode bits and pieces.

I gazed at the pages, drawn in by the Urdu script and feeling enchanted that someone had created these words with such dexterity. I exulted even more at the newfound reading skills which allowed me to decode bits and pieces.

I wasn’t linguistically equipped to easily decipher the whole letter. The first few lines were straightforward enough. His postal address was repeated, this time in Nastaliq. However, tellingly for this bibliophile, he did not provide any email or phone details. A standard polite greeting was given, and Sami went on to introduce himself. He explained he was a food science graduate but that his گھر کا ماحول – ghar kā maḥol or home environment – had instilled in him a love of literature. Here he name-checked two authors. The first was a writer whose detective novels I had been harbouring an ambition of reading in the original Urdu: Ibn-e-Safi. The other was new to me but my teacher Fareeha later told me he is brilliant: Ishtiaq Ahmed, who wrote spy novels as well as crime fiction. Sami had devoured all the thrillers by these novelists, both of whom are no longer alive. After these childhood peregrinations, he told me, his reading expedition had continued uninterrupted.

Sami had been following my literary columns for years. Now he expressed pleasure at my affinity for his country – and, latterly, for his language, Urdu. He told a cutting joke against his own people:

یو.کے. جانے کے لیے آدھے سے زیادہ پاکستانی ہمہ وقت تیار رہتے ہیں اور منہ ٹیڑھا کر کے انگریزی بولنے میں بے انتہا فخر محسوس کرتے ہیں۔ سلام ہے آپ کی اردوے اس قدر محبت پر !

UK jāne ke liye ādhay se zyādah Pākistānī hama waqt tayyār rehtay hain aur munh teṛhā kar ke angrezī bolne mein be-intihā fakhr mehsoos karte hain. Salām hai āp kī Urdū par is qadr mohabbat!

He wryly compared my interest in Urdu to his belief that more than half of Pakistan’s citizens are ready to leave their country for the UK, and that they take immense pride in speaking English despite their contorted accents. ‘I salute your love for Urdu!’ he added. Ironically, though, were he to hear me speak, he’d find my own accent more twisted than his compatriots’.

Sami’s written Urdu was beautiful and witty, but also challenging for me because of the high-register vocabulary in places. For example, in relation to his and my respective enthusiasms, he twice used the Persianate term خصوصی وابستگی, khuṣūṣī wābastagī, which I had to look up for its meaning of special affiliation or exclusive attachment. I dutifully wrote this down in my vocabulary list and resolved to use it in future conversations or writing exercises. I imagined my friends’ wah wahs if I busted out a khuṣūṣī wābastagī while discussing the latest movie release.

As I continued reading, I turned to artificial intelligence for more help, since my own natural abilities weren’t up to the task. Not only did Sami’s diction soar but getting familiar with his hand was also initially hard for me, as someone who almost always reads digitized text. Luckily, his writing was strikingly neat and structured, with a well-formed, evenly spaced Urdu script that maintained a steady slant and consistent letter size. Sami’s bold emphasis on certain words – particularly at the end of sentences – hinted at strong emotions, perhaps conviction, determination, or even a plea for understanding. The smooth flow of the text and the lack of excessive corrections indicated discipline and confidence, while occasional flourishes (like turning three-dot nuqṭe into a swooping arc resembling an apostrophe) lent a personal, expressive touch to Sami’s writing style. Handwriting isn’t just about the sense; it’s a window onto the writer’s sensibility.

I did what I call shining the Google Translate torch on the pages to make sure it didn’t degenerate into a love letter – or, worse, soft porn. This step seemed necessary before showing it to Fareeha, who is quite religious. The app is a lifesaver, as it can translate both handwriting and digital text. I was relieved to find that, unlike some of the emails I’ve received, the message was neither sexualized nor abusive. In fact, the letter was a pure gift, and its ideas have been echoing in my mind ever since.

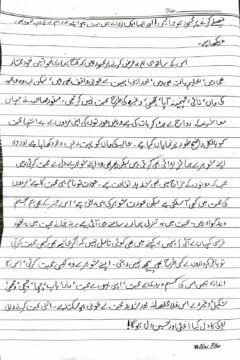

In my most recent Dawn column, I’d discussed the A-level text Aangan by Khadija Mastur. The letter writer knew Mastur’s name and had perhaps heard the title – which translates as Inner Courtyard or The Women’s Courtyard – from his elders. My essay spurred him to buy and read the book. He went on to pen several pages of thoughtful literary criticism about the novel, remarking that he had never read anything like it before. This authorial inventiveness, he speculated, is perhaps why Aangan didn’t receive the recognition it deserved in its time.

In my most recent Dawn column, I’d discussed the A-level text Aangan by Khadija Mastur. The letter writer knew Mastur’s name and had perhaps heard the title – which translates as Inner Courtyard or The Women’s Courtyard – from his elders. My essay spurred him to buy and read the book. He went on to pen several pages of thoughtful literary criticism about the novel, remarking that he had never read anything like it before. This authorial inventiveness, he speculated, is perhaps why Aangan didn’t receive the recognition it deserved in its time.

He and I agreed that the novel’s unique aspect lies in its portrayal of a woman pursued with relentless ardour by a handsome and cultivated man named Jameel. What makes it arresting is that the protagonist Aliya uses her intellect and decision-making powers to reject Jameel. Notwithstanding the romantic novel framework and Jameel’s allure, Aliya realizes that certain disappointing personality traits make him undeserving of her love. Sami wrote a paragraph that my AI pals and I carry across to English as follows:

You have rightly pointed out that purdah isolates girls significantly, especially in relation to men. Women interact extensively among themselves, but they don’t get to meet decent men. If the men in their own families are good, it’s fine; otherwise, they must manage with whatever they have. This issue affects men too. That’s why Jameel remains fixated on Aliya in Aangan – she is the only well-educated girl in his family. Even if there are similar girls in the neighbourhood, how would he know? What’s the point of hiding girls to the extent that both men and women end up making poor decisions? We regularly see such scenarios play out before our eyes even today.

Sami thanked me for opening him up to this novel by a woman writing in the 1960s but reflecting on the period leading up to and just after the 1947 partition of the South Asian subcontinent. He noted that the vivid depiction of morning and evening routines, along with the overall atmosphere Mastur creates, adds further lustre to the novel. While reading, he felt as if he were sitting in pre-partition India. He sounded like a very open-minded Gen Z individual, much like several of the characters in the wonderful drama serial Tan Man Neelo Neel. In fact, most of the young people I’ve met from Pakistan have no issue with India or Indians. Fareeha often says, ‘We’re the same people.’ Sami signed his epistle off with the request, ‘Please continue your journey of learning and reading Urdu, and keep including people like us in your journey.’

Moved by Sami’s letter, I wanted to write an acknowledgement and gain some learning from the process. I took the sheets of paper to Fareeha in the hope she could help me craft a reply worthy of his marvellous missive. It took over two hours to write several drafts, culminating in this short, stilted response, which still had lots of crossings-out:

Respected Sami sahib,

Greetings. I’m Claire, and I was both delighted and surprised to receive your letter.

In this digital age, writing letters is not a common practice, and receiving one all the way from Pakistan is really an honour for me. Taking the time to write a letter amid a busy life is an admirable thing.

Reading your letter brought me joy. Knowing that you read and enjoy my columns means a lot to me. It is even more gratifying to hear that my writing encouraged you to read Aangan and that you not only appreciated it but understood it deeply.

Even though you come from a science background, your passion for literature is proof of the rich intellectual environment your parents fostered in your home. Your letter revealed an important insight to me: as a man, you recognized that purdah doesn’t only affect women. If purdah is to be observed, then men play at least an equal part. Anyway, wherever in the world they are, in their gaze, their words, and their behaviour, the restraint and respect of men like you help women to feel safe and calm.

I look forward to continuing this conversation and hope you will keep reading and engaging with Urdu literature.

All good wishes,

Claire

After musing on this exchange, I couldn’t help but return to some previous meditations. In a previous post for 3QD about Urdu handwriting, I shared how I resisted its graft for so long. After all, who was I going to write to in this day and age? Now I have my answer. I’ve also received a valuable language lesson, and – perhaps – found a pen friend across continents, worldviews, and generations.