by Nils Peterson

One of my favorite ways of beginning the morning is by having Siri put on “Grand Canyon Suite” by Ferde Grofe. It’s pleasant and gives a sense of the day beginning and going on its way. Also, in the middle, if you’re an old guy like me, you’ll hear the music that used to introduce “Call For Phillip Morreez,” the voice of Johnny, the hotel bell boy calling across America inviting us all to smoke. At one time I wanted to be an ad man. I wonder if I would have refused to work on a cigarette ad at the possible cost of my job. Of course, the question wouldn’t have come up when I was younger and smoked, but if I had been older and knew better, what would I have done. In truth, I’m not sure. There are many ways of convincing yourself that you’re not doing a wrong thing.

I have the door to the patio outside my second floor flat (I like that British word better than the American apartment) to let some fresh air in in the morning. I never sit on my patio though it would often seem to be attractive except it overlooks Greenwood Avenue N where the traffic is constant and noisy. Just now a car went by claiming it’s place for a larger share of world domination by having its muffler removed. There are many of those and we live too by a fire house and emergency vehicles emerge both night and day. I’ve just ordered some earpods with a noise cancelling feature. Maybe that can recover lost space or at least the ability to listen to music with the door open.

I wanted to write this this morning because of a sentence in my notebook that I read in the NY Times Book Review. The book (it’s so long ago now, I can’t remember title or author) is about a woman’s attempt to live “an honest life. More than that,” actually: “a good life. You can do nothing or you can do better.” What a helpful last sentence. It relieves you from the burden of solving the world’s difficulties while offering a way to live well. “You can do nothing or do better.” I hope I can at least do something in some ways. While I was brooding over this, Facebook recovered something I wrote years ago, forgot about, but now find helpful. Read more »

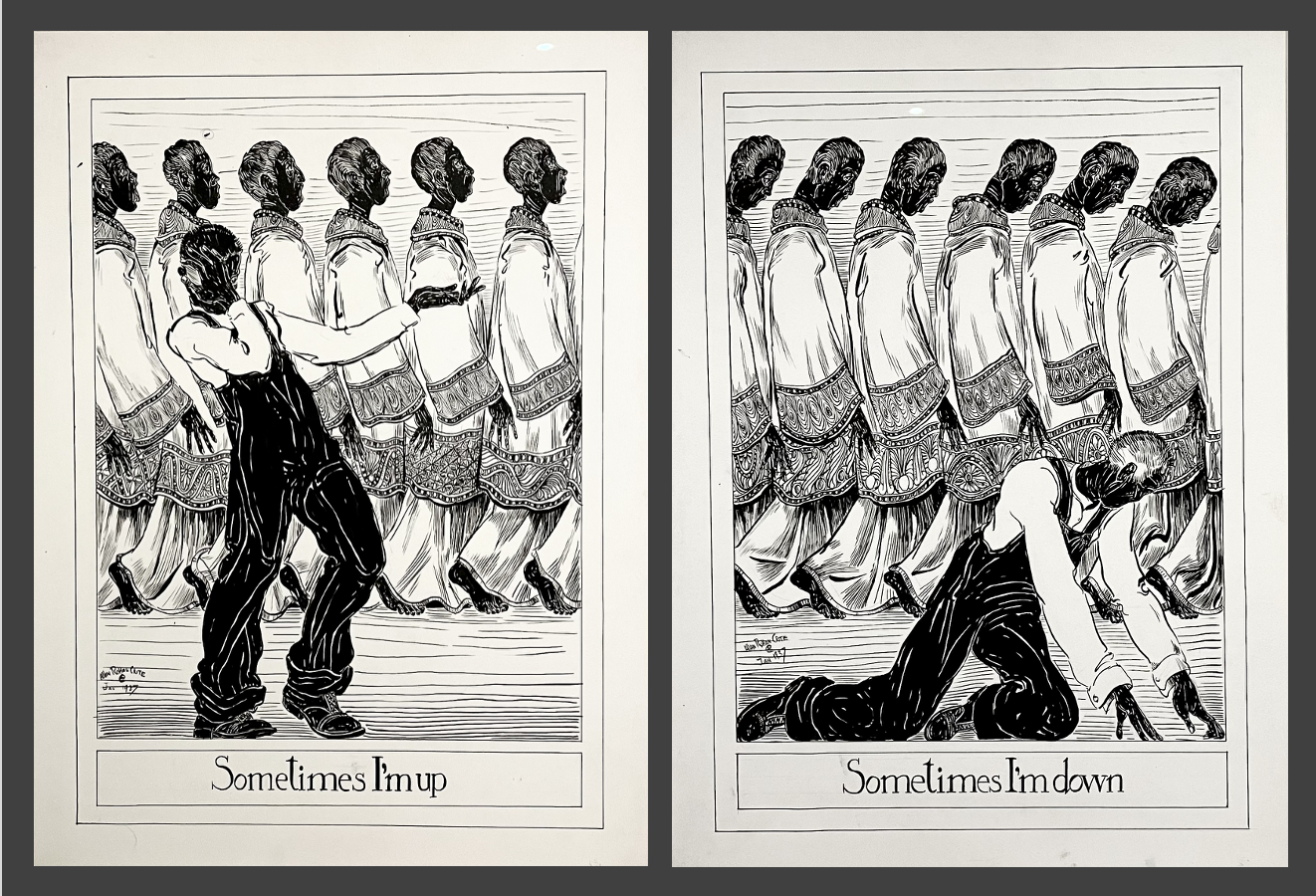

Allan Rohan Crite. Sometimes I’m Up, Sometimes I’m Down. Illustration for Three Spirituals from Earth to Heaven (Cambridge, Mass., 1948),” 1937.

Allan Rohan Crite. Sometimes I’m Up, Sometimes I’m Down. Illustration for Three Spirituals from Earth to Heaven (Cambridge, Mass., 1948),” 1937.  Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,

We sometimes say that someone is living in the past, but it seems to me that the past lives in us. It lives in our houses; it lies all around us. As I write this, I’m sitting on the couch under two blankets crocheted by my grandmother, who was born around the turn of the 20th century. The laptop sits on a folded blanket that came from Mexico via a friend years ago. And that’s just the surface layer. My closets and file cabinets are also full of the past.

We sometimes say that someone is living in the past, but it seems to me that the past lives in us. It lives in our houses; it lies all around us. As I write this, I’m sitting on the couch under two blankets crocheted by my grandmother, who was born around the turn of the 20th century. The laptop sits on a folded blanket that came from Mexico via a friend years ago. And that’s just the surface layer. My closets and file cabinets are also full of the past.

Sughra Raza. Bey Unvaan. January, 2026.

Sughra Raza. Bey Unvaan. January, 2026.