by John Allen Paulos

A bit of information is common knowledge among a group of people if all parties know it, know that the others know it, know that the others know they know it, and so on. It is much more than “mutual knowledge,” which requires only that the parties know a particular bit of information, not that they be aware of others’ knowledge of it. This distinction between mutual and common knowledge has a long philosophical history and has long been well-understood by gossips and inside traders. In modern times the notion of common knowledge has been formalized by David Lewis, Robert Aumann, and others in various ways and its relevance to everyday life has been explored, most recently by Steven Pinker in his book When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows.

A bit of information is common knowledge among a group of people if all parties know it, know that the others know it, know that the others know they know it, and so on. It is much more than “mutual knowledge,” which requires only that the parties know a particular bit of information, not that they be aware of others’ knowledge of it. This distinction between mutual and common knowledge has a long philosophical history and has long been well-understood by gossips and inside traders. In modern times the notion of common knowledge has been formalized by David Lewis, Robert Aumann, and others in various ways and its relevance to everyday life has been explored, most recently by Steven Pinker in his book When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows.

I discussed common knowledge in my books Once Upon a Number and A Mathematician Plays the Stock Market and illustrated it with the following parable, which suggests its power.

The parable takes place in a benightedly sexist village of uncertain location. In this village there are many married couples and each woman immediately knows when another woman’s husband has been unfaithful but not when her own has. The very strict feminist statutes of the village require that if a woman can prove her husband has been unfaithful, she must kill him that very day. Assume that the women are statute-abiding, intelligent, aware of the intelligence of the other women, and, mercifully, that they never inform other women of their philandering husbands. As it happens, 20 of the village men have been unfaithful, but since no woman can prove her husband has been so, village life proceeds merrily and warily along. Then one morning the tribal matriarch comes to visit from the far side of the forest. Her honesty is acknowledged by all and her word is taken as truth. She warns the assembled villagers that there is at least one philandering husband among them. Once this fact, already known to everyone, becomes common knowledge, what happens? Read more »

Sughra Raza. Departure. December 2024.

Sughra Raza. Departure. December 2024.

In recent years chatbots powered by large language models have been slowing moving to the pulpit. Tools like

In recent years chatbots powered by large language models have been slowing moving to the pulpit. Tools like

One of my New Year’s resolutions was to read one of the “classics of fiction” each month this year. I’m happy to report that I’m on pace to succeed.

One of my New Year’s resolutions was to read one of the “classics of fiction” each month this year. I’m happy to report that I’m on pace to succeed.

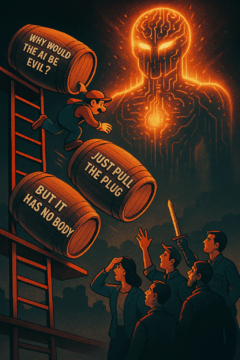

As AI insinuates itself into our world and our lives with unprecedented speed, it’s important to ask: What sort of thing are we creating, and is this the best way to create it? What we are trying to create, for the first time in human history, is nothing less than a new entity that is a peer – and, some fear, a replacement – for our species. But that is still in the future. What we have today are computational systems that can do many things that were, until very recently, the sole prerogative of the human mind. As these systems acquire more agency and begin to play a much more active role in our lives, it will be critically important that there is mutual comprehension and trust between humans and AI. I have

As AI insinuates itself into our world and our lives with unprecedented speed, it’s important to ask: What sort of thing are we creating, and is this the best way to create it? What we are trying to create, for the first time in human history, is nothing less than a new entity that is a peer – and, some fear, a replacement – for our species. But that is still in the future. What we have today are computational systems that can do many things that were, until very recently, the sole prerogative of the human mind. As these systems acquire more agency and begin to play a much more active role in our lives, it will be critically important that there is mutual comprehension and trust between humans and AI. I have

“A clearly written and compelling account of the existential risks that highly advanced AI could pose to humanity.” — Ben Bernanke

“A clearly written and compelling account of the existential risks that highly advanced AI could pose to humanity.” — Ben Bernanke