by Gary Borjesson

The happiest, most fulfilled moments of my life have been when I was completely aware of being alive, with all the hope, pain, and sorrow that entails for any mortal being. —Jenny Odell

Applied Philosophy

Back when I was a professor, I loved teaching intro to philosophy courses. Philosophy’s essence comes alive when working with people whose view of themselves and the world is still open and underway. One of the texts I used was Aristotle’s timeless exploration of friendship in the Nicomachean Ethics. I hoped it would win the students over, showing them how interesting and practically minded philosophy could be. We spent a month exploring what’s known about friendship, how it is known, and why it matters.

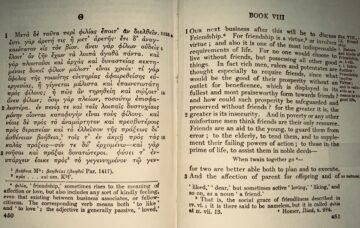

We don’t have a month together, but think of this essay as an invitation to go deeper into this most familiar of subjects. I offer three big things worth knowing about friendship. First, it’s worth knowing why friendship matters, why we agree with Aristotle when he says that ‘even if we had all the other goods in life, still no one would want to live without friends.’ That friendship matters is obvious, which is why the current crisis in friendship (especially among men) is getting so much attention. Second, it’s worth knowing that there are three kinds of friendship; recognizing these can shed light on how our own friendships work. Finally, it’s worth knowing that friendship and justice go hand in hand. This may seem obvious; after all, when is it ever friendly to be unjust? Nevertheless, the implications of this provoked students, and no doubt will provoke some readers.

1. Why Friendship Matters: It Empowers and Enlivens

Aristotle opens his discussion of friendship by remarking that friendship—‘when two go together’—makes us more able to think and act. He’s alluding to a famous passage from the Iliad, where war-like Diomedes volunteers for a dangerous spying mission behind enemy lines, saying

But if some other man would go with me,

my confidence and mood would much improve.

When two go together, one may see

the way to profit from a situation

before the other does. One man alone

may think of something, but his mind moves slower.

His powers of invention are too thin.

Diomedes chooses resourceful Odysseus as his companion: “If I go with him, we could emerge from blazing fire and come home safe, thanks to his cleverness.”

This is our song as social animals, that by going together we are safer and our prospects for a good outcome improved. In evolutionary terms, friendship is empowering because cooperation is a non-zero-sum game that confers a greater-than-the-sum-of-the-parts power to the friends. Having friends is a means of better adapting to the world.

But friends aren’t just an empowering means to an end, they can also be an enlivening end in their own right. Sure, we like how they can benefit us, but in better friendships what we mainly like is the friend themselves, and we feel enlivened in their company. For Aristotle, as for us, one of the things that humans live for and find most fulfilling is this experience of being “completely aware of being alive.” In the epigraph to this essay, Jenny Odell isn’t writing about friendship, but she beautifully captures what friendship can offer: an amplified sense of our aliveness and flourishing.

When I was a kid and heard music I loved, my first impulse was to share it with someone; I still feel delighted when I see what has moved me also moving a friend. Another example: the other night I was speaking about a patient during a meeting of our psychotherapist consult group. By the end of our hour-long conversation, I felt, yes, more empowered to work with him. But, as important, I also felt enlivened by having what was on my mind taken up, expanded on, reflected on from different angles, and given back to me by this small group of attentive friends. I felt my mind expanding in such good company, the work with this man somehow coming more to life, made more real and meaningful for having been shared with friends.

Friendship matters because it contributes to flourishing, which is the ultimate good we all seek. Aristotle defined flourishing as being actively engaged in meaningful endeavors. It could be cooking or running or making art or conversing about philosophy. But whatever we’re doing, if we can do it with friends, then our felt sense of flourishing is enlivened. That friendship amplifies our power and our happiness is obvious, but remarkable nonetheless.

2. Three Ways of Being Friends

Students would ask how Aristotle could be so confident there are just three kinds of friendship. I’d point to his remark that there are as many kinds of friendship as there are likable things, and he thought there were three: (1) something is liked because it is useful; (2) because it is pleasurable; or (3) because it is good in its own right. Most students found this a pretty exhaustive way of carving up likable things, but they were troubled that Aristotle regarded this as a hierarchy, with useful friendship at the bottom and the friendship of the ‘good’ at the top. Among other things, they worried this implied that some friendships were less good because they had some bad mixed in, causing them to fall short of the ideal friendship.

On the contrary, Aristotle’s ranking reflects his definition of friendship, not any moral judgment. In fact, there is no badness, nothing wrong, with friendships based on the use or the pleasure we receive from them. It’s just that, by definition, these friendships aren’t being (or even trying to be) all that friendships can be. Aristotle’s point is that the more complete a friendship is, the more it is the friend who is liked rather than the benefits of use and pleasure that do also come with being friends. Thus the friendship is pursued for its own sake. Notice how this hierarchy reflects the earlier distinction between the empowering (instrumental) and the enlivening (for its own sake) aspects of friendship.

a. Useful Friends

All friendships are based on the mutual awareness of liking each other. What distinguishes them is the reason for being friends—what we’re liking. Useful friendships exist because it is mutually advantageous to carpool or work-out together or babysit each other’s kids or dogs, and so on. How do we know it’s mainly a useful friendship? Because—warm and sincere as the mutual liking is—when the use is gone, so is any active engagement in the friendship.

b. Pleasurable Friends

Drinking buddies, friends who get together to watch (or play) games, or companions who enjoy each other’s wit—all such friendships are sustained by pleasure. These more resemble true friendship because pleasure is a good we seek for its own sake. (Students readily agreed with Aristotle on this point!) The pleasure of being in a friend’s company is an end in itself. In addition, these friendships naturally tend to be more expressive of who each friend is, and what they share in common—likeness of interests, pleasures, even perhaps character. Still, they are limited because what’s liked primarily is the pleasure, not the person.

c. Virtuous Friends

In the most complete form of friendship, what we love is the friend themselves, their ‘virtuous’ way of being in the world. Now, the word virtue is so freighted with moralizing overtones that the original meaning of the Greek word it translates—aretḗ—has been lost to our English ear. Aretḗ means excellence. Admiring a friend’s wonderful cooking, you are admiring her aretḗ as a cook. Likewise with a friend’s generosity or courage or musicality or sense of humor or sailing skills, and so on. Aretḗ concerns something well and beautifully done, or someone living well and beautifully. So, when I use ‘virtue,’ think of this—not some Victorian sitting room stuffy with the righteous whiff of moral judgment.

Virtue friendships are also likely to be pleasurable and useful—they are the most complete after all! Indeed, all the ways of being friends usually involve a mix of the three. For example, my weekly Sunday morning long run with a friend offers pleasure and use. (The use, as Diomedes noted, is that hard things are easier with a friend along!) And though ours is primarily a friendship of pleasure, virtues too are in the mix. We trust each other to show up, rain or shine. Still, our enjoyment of running is the basis of the friendship. Whereas in virtue friendships, even if the pleasure and use were gone, we’d still be friends—unless the friend changed substantially.

Which brings us to another sticking point for students. Aristotle observed that virtue friendships exist between people who are similar and similarly virtuous. He took it as self-evident that those who are not good themselves cannot make good, lasting friendships. Students disliked the apparent elitism, and argued instead that good friendships are possible between all kinds of people, not just people who are similar and good. We’ll see why this romantic view fell apart for the students when we consider why the friendly is the just.

With virtue friends we feel most ourselves. Because such friends are similarly minded, being with them expands our experience of ourselves. You can hear this in the Greek proverb, ‘A friend is another self.’ There’s not the least hint of narcissism here because such love isn’t egoistic; rather we are enlivened by being with what’s good and true in the friend and ourselves. Thus these friendships are best in the sense of being the most complete expression of what friendship can be, of being an end in themselves, and of amplifying what is best in us.

3. The Friendly Is the Just

What makes the connection between friendship and justice so provocative is the implication that we keep score and judge our friends. Where’s the love? my students would ask. What about the virtue of loving a friend unconditionally? Aristotle agrees that this is a virtue of the best friendships, but it is an acquired one. While friends may instantly desire to be close, friendship needs time to develop. He quotes the proverb that would-be friends must share “much salt”—many meals together—before becoming true friends. With time comes experience, through which friends get to know each other.

This of course is where that dreaded judgment comes into play. But it didn’t take long for students to recognize that judgment was actually their friend, expressing care for the emerging relationship. What does discerning experience teach about how much reciprocation, how much justice, and thus how far we can trust each other? We explored this by looking at why some friendships ended, or never really took hold, while others grew and flourished. Students could hardly deny that it’s hard to be friends with someone who doesn’t reciprocate or treat us fairly. Our discernment protects us from making false friends, while building trust with those who prove to be true. So, early on in friendships we keep score in order to learn whether, in fact, we need to continue keeping score. It’s in these ways that the virtue of unconditional love grows from the humble soil of conditional love. Its prerequisites, safety and trust, are conditioned on the repeated experience of being treated well and fairly—which turns out to feel amazingly friendly.

Modern research is confirming these ancient insights about friendship. Research is showing how ‘similar neural responses predict friendship.’ In other words, likeminded people predictably gravitate to one another, just as the proverbs ‘like attracts like’ and ‘a friend is another self’ suggest. But in news that would be heartening to my students, researchers are also discovering how we can start out not being likeminded, but by spending time together can ‘fall into neural synchrony with others.’ Indeed, this is another gift of time: the time needed to figure out how to get along with each other. For friendship, like dancing, is something you get better at with practice. Researcher Thalia Wheatley asks: “When our brains are dancing together, what does that look like? And why do some people dance together better than others?”1Quoted in Lydia Denworth’s fine book, Friendship: The Evolution, Biology, and Extraordinary Power of Life’s Fundamental Bond. We’re beginning to discover the neural basis of what Aristotle understood long ago—that friendship involves a deep synchronization between minds, a coupling through which we become more than we could be alone.

Note: This is the first of a series I plan on friendship. My always-free Substack has links to more of my writing, including related pieces on the art, science, and philosophy of alliances in general.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Footnotes

- 1Quoted in Lydia Denworth’s fine book, Friendship: The Evolution, Biology, and Extraordinary Power of Life’s Fundamental Bond.