by David J. Lobina

One of the most disappointing aspects of modern life is seeing peers in academia, and intellectuals in general, share their personal and private selves on social media.

Now, it is not the case that prior to social media one didn’t know anything about the personalities of many academics or intellectuals, but it was all a bit more circumspect, and salutary. The issue of whether there was a conflict between a person’s work and their personal lives or beliefs would rarely arise, for instance. Most academics are not public figures anyway, and before social media the vast majority of them received no wide exposure anywhere (let’s put public intellectuals to one side for the time being).

The problem now is that anyone can self-publish and self-expose on the internet, and so we suddenly have to face the fact that many clever academics and intellectuals are really out there and can also behave like, well, idiots.[i] There is something about social media, and it only takes a single look at Twitter/stupid-name-of-X to see what a cesspool social media can be. Umberto Eco may have been right when he pointed out that social media had brought loads of stupid conversations, and stupid people, out of the bar and moved them into the wide open world, but to see academics behaving badly in the public sphere is too close to home for comfort.[ii]

When I was an undergraduate student and had already decided I wanted to attend graduate school to study linguistics and cognitive science more generally, I hadn’t met or encountered any of the authors I had read up to that point, and so it was all a bit of a mystery what these academics were like (and I don’t think I ever even considered the question, in fact). Things started to change when I joined the linguistics department at University College London (UCL) as a master’s student in 2004, which at the time was a prominent Chomskyan stronghold and boasted some true heavyweights in the field – Deirdre Wilson of Relevance Theory was probably the most famous scholar there.

The overall setting as well as the teaching were fairly formal at UCL, and even though we got to know the teaching staff a bit, including over drinks at a local pub, little of substance was given away by them at any time in terms of their personalities or belief systems. They were all nice and decent, and no more than that – nothing that took place during my time at UCL had an effect on how I viewed my teachers’ works or how I read their writings.

Things changed again when I moved next door soon after in order to study philosophy at Birkbeck College. Philosophers were far more outspoken and way more extrovert, and I especially recall a conversation with a tutor where I brought up the ideas of one philosopher as a possible topic for an essay, only to be told that the work of this particular philosopher was naïve and that they (who?) had already discussed it with each other at length at conferences – so is that how work in philosophy progresses?!

My experience as a philosophy student also had little impact on my reading of philosophical works, including that of this tutor, but I did start to see people’s personalities seeping through a little bit more (I do remain surprised by my exchange with the tutor, though). After that, as a PhD student I started attending conferences and workshops, and in these events you certainly socialise with other academics – here you are indeed exposed to people’s personal selves a lot more. But conferences remain professional events and there are constraints and filters in place there too, even explicitly (shit happens, of course). The problem with social media is that it seems to bring out the worst in people, academics or not, and there are no constraints or filters at all.

Seeing other academics, and even public intellectuals, misbehave on social media always reminds me of the reaction I typically have when watching self-financed or entirely unhinged films such as Megalopolis or Fellini’s Casanova – if only a producer had said no the director here or there (or actually everywhere!).[iii] Geniuses need oversight, so imagine your average academic… But I still do not believe that anyone’s behaviour or personal beliefs ought to have an effect on how their scholarly work is evaluated, and in any case it’s not like anyone’s personality transparently comes through their writings for the most part. There are exceptions, of course: both Noam Chomsky and Jerry Fodor (to name two of my academic pillars, as it were) have very distinctive, even personal, writing styles (there used to be a Chomsky bot which closely mimicked his style), but for the most part academic writing is pretty dry and personal flourishes are frown upon – I should know: the number of times a reviewer has said to me that the paper’s style is not appropriately academic.[iv]

Surprisingly, you do find yourself having to defend the actions of your heroes to others on occasion in the very terms I have argued should not be the case. This has happened to me when it comes to Chomsky, though I am using the term “hero” loosely here, for despite the title of this post I do not actually believe in having heroes, role models, or having to see myself or be represented anywhere. The opposite view belies such an elitist, top-down take on the world, and I don’t think the world works like that at all – you need to be able to afford having role models or heroes to begin with, and in very unequal societies that doesn’t happen all that often (and if it does, it’s unlikely to improve your situation).

In the case of Chomsky, to get back on track, I find most of his views outside of his scholarship – that is, in his political and cultural writings – the most reasonable and knowledgeable available anywhere, and it is these views that I have had to defend in the past. A case in point is the following situation, which I have encountered many times when interacting with like-minded people. To some of my generation, it was a shock to see Chomsky visit Venezuela and meet Hugo Chávez, especially considering that he seemed to act a little too deferential to Chávez to boot. A clip of the encounter does make for some uncomfortable viewing now, and even though it was a very un-Chomsky thing to do, I nevertheless disagree with the reaction I have often encountered – basically, the claim that Chomsky’s reputation (within left-wing circles, I assume, and perhaps in general) was ruined after this showing.

I found the claim worrying and mistaken; surely this episode doesn’t change anything regarding what Chomsky writes or says about, say, the Israel-Palestine conflict (god, do we need him these days). After all, there is no discernible relationship between what Chomsky thinks and does regarding Chávez and what he writes and advocates regarding the Israel-Palestine conflict, and it would be entirely unwarranted to dismiss his take on the latter based on the former. In addition, it has always seemed to me strange to become so worked up about meeting someone like Chávez, when this would not have been the case at all had Chomsky met with Obama instead at the time. And yet, on many objective measures – say, number of targeted killings conducted or approved – Obama is far worse than Chávez (an unfair comparison, perhaps; US presidents fair badly against most other contemporaries).

*****

But never mind. In the end, the problem is not really with having heroes or role models per se, whatever their actual, real effects on people’s lives; the problem is that it is a mistake to choose heroes or role models that are still alive, for they are bound to disappoint you in one way or another sooner or later – you are at their mercy as long as they live, and that’s intolerable. This of course applies to intellectual heroes as much as it applies to any kind of hero; I’m still upset about some of Roger Federer’s losses. Choose a dead hero instead, I say, research them well, and make sure you can live with everything they ever said and did.

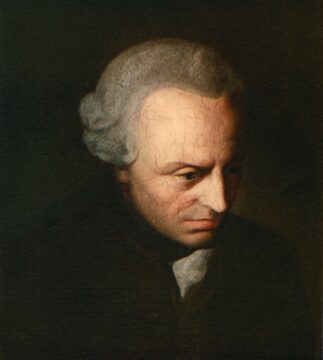

I think Immanuel Kant is a safe choice here, or perhaps Athanasius Kircher.

[i] I can hear some of my friends go ‘oh god, not another dig at Jason Stanley!’. Everyone in philosophy has or knows a Jason Stanley story, I suppose…

[ii] Eco’s point is one of the reasons why I have never really liked bars – and even less pubs in England, with their sticky tables, warm beer, and dirty 40-year-old carpets.

[iii] Megalopolis has to be seen to be believed, really (see this review for a fully deserved put-down). The analogue of a film producer for an academic is either a journal reviewer or an editor from a book publishing house, both of whom can often be useful (I personally love book editors, but naturally hate reviewer number 2, along with journal editors who are always weirdly deferential to awful reviewers). In another life, I would have been a filmmaker and I would have shot a remake of Wild Strawberries, with Marlon Brando in the lead (for some reason, Brando was a (loose) hero of mine in my early 20s and I even read a biography of his, an incredibly dull thing to do, as it happens).

[iv] The more famous you become, the more leeway you are given – compare the early writings of Chomsky and Fodor with their later stuff and there is quite a gulf in style there (and confidence).

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.