by Gary Borjesson

You know you have loved someone when you have glimpsed in them that which is too beautiful to die. —Gabriel Marcel

Meno famously asked Socrates whether virtue could be taught. True to form, Socrates pressed the deeper question: what is virtue, anyway? I’m going to save myself and the reader considerable grief by taking for granted that we know roughly what virtue is—when we see it. That’s not to say we can’t get mind-numbingly confused, as Meno did, if we start philosophizing. What I want instead is to look at how this familiar and vital idea appears in practice.

Specifically, I’ll show how virtue comes to light in the love and friendship of Darcy and Elizabeth. I know of no better depiction than Jane Austen’s in Pride and Prejudice. I’ve chosen it because Austen’s view of virtue is philosophic in its depth and precision, and because it’s a wonderful story known to many readers.

Austen’s title announces the theme of virtue, by pointing to the obstacles Darcy and Elizabeth face to having more of it. I say “more”, because, contrary to a common opinion, virtue is not a thing but an activity that falls on a continuum. With regard to virtue, we behave better and worse, have better and worse days; some of us lead better or worse lives relative to others. We call a way of acting and living virtuous when it aligns with the good or true or beautiful. (Austen would agree with Aristotle’s gloss of virtue (areté) as excellence in action and character.)

What makes Darcy and Elizabeth so compelling is that they take their lives seriously, which is to say they want to be virtuous. Indeed, each of them assumes they already are! The novel’s drama unfolds in the space between who they think they are, and who they actually are—which is not so virtuous as they thought! But while they have high opinions of themselves, they are not egotists, for they don’t want merely to appear virtuous to others and themselves, they want actually to be good and true, and to live in a beautiful way. That’s why both despise flattery and falseness, whereas an egotist invites it. Read more »

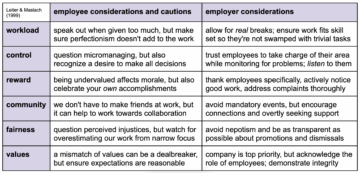

I started reading about burnout when I walked away from teaching earlier than expected. Suddenly, I couldn’t bring myself to open that door after over thirty years of bounding to work. A series of events wiped away any sense of agency, fairness, or shared values. Their wellness lunch-and-learns didn’t help me, and I soon discovered I’m not alone.

I started reading about burnout when I walked away from teaching earlier than expected. Suddenly, I couldn’t bring myself to open that door after over thirty years of bounding to work. A series of events wiped away any sense of agency, fairness, or shared values. Their wellness lunch-and-learns didn’t help me, and I soon discovered I’m not alone.

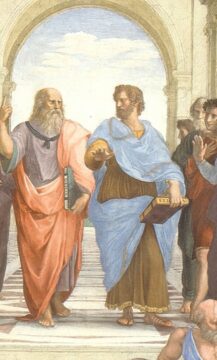

For many of the ancient philosophers that we still read today, philosophy was not only an intellectual pursuit but a way of life, a rigorous pursuit of wisdom that can guide us through the difficult decisions and battle for self-control that characterize a human life. That view of philosophy as a practical guide faded throughout much of modern history as the idea of a “way of life” was deemed a matter of personal preference and philosophical ethics became a study of how we justify right action. But with the recognition that philosophy might speak to broader concerns than those that get a hearing in academia, this idea of philosophy as a way of life

For many of the ancient philosophers that we still read today, philosophy was not only an intellectual pursuit but a way of life, a rigorous pursuit of wisdom that can guide us through the difficult decisions and battle for self-control that characterize a human life. That view of philosophy as a practical guide faded throughout much of modern history as the idea of a “way of life” was deemed a matter of personal preference and philosophical ethics became a study of how we justify right action. But with the recognition that philosophy might speak to broader concerns than those that get a hearing in academia, this idea of philosophy as a way of life