by Gary Borjesson

The happiest, most fulfilled moments of my life have been when I was completely aware of being alive, with all the hope, pain, and sorrow that entails for any mortal being. —Jenny Odell

Applied Philosophy

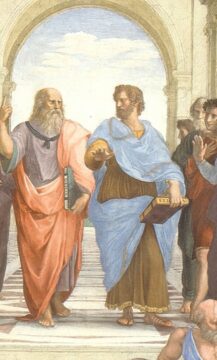

Back when I was a professor, I loved teaching intro to philosophy courses. Philosophy’s essence comes alive when working with people whose view of themselves and the world is still open and underway. One of the texts I used was Aristotle’s timeless exploration of friendship in the Nicomachean Ethics. I hoped it would win the students over, showing them how interesting and practically minded philosophy could be. We spent a month exploring what’s known about friendship, how it is known, and why it matters.

We don’t have a month together, but think of this essay as an invitation to go deeper into this most familiar of subjects. I offer three big things worth knowing about friendship. First, it’s worth knowing why friendship matters, why we agree with Aristotle when he says that ‘even if we had all the other goods in life, still no one would want to live without friends.’ That friendship matters is obvious, which is why the current crisis in friendship (especially among men) is getting so much attention. Second, it’s worth knowing that there are three kinds of friendship; recognizing these can shed light on how our own friendships work. Finally, it’s worth knowing that friendship and justice go hand in hand. This may seem obvious; after all, when is it ever friendly to be unjust? Nevertheless, the implications of this provoked students, and no doubt will provoke some readers.

1. Why Friendship Matters: It Empowers and Enlivens

Aristotle opens his discussion of friendship by remarking that friendship—‘when two go together’—makes us more able to think and act. He’s alluding to a famous passage from the Iliad, where war-like Diomedes volunteers for a dangerous spying mission behind enemy lines, saying

But if some other man would go with me,

my confidence and mood would much improve.

When two go together, one may see

the way to profit from a situation

before the other does. One man alone

may think of something, but his mind moves slower.

His powers of invention are too thin.

Diomedes chooses resourceful Odysseus as his companion: “If I go with him, we could emerge from blazing fire and come home safe, thanks to his cleverness.”

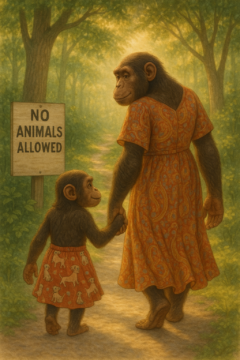

This is our song as social animals, that by going together we are safer and our prospects for a good outcome improved. In evolutionary terms, friendship is empowering because cooperation is a non-zero-sum game that confers a greater-than-the-sum-of-the-parts power to the friends. Having friends is a means of better adapting to the world.

But friends aren’t just an empowering means to an end, they can also be an enlivening end in their own right. Read more »