by John Allen Paulos

A bit of information is common knowledge among a group of people if all parties know it, know that the others know it, know that the others know they know it, and so on. It is much more than “mutual knowledge,” which requires only that the parties know a particular bit of information, not that they be aware of others’ knowledge of it. This distinction between mutual and common knowledge has a long philosophical history and has long been well-understood by gossips and inside traders. In modern times the notion of common knowledge has been formalized by David Lewis, Robert Aumann, and others in various ways and its relevance to everyday life has been explored, most recently by Steven Pinker in his book When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows.

A bit of information is common knowledge among a group of people if all parties know it, know that the others know it, know that the others know they know it, and so on. It is much more than “mutual knowledge,” which requires only that the parties know a particular bit of information, not that they be aware of others’ knowledge of it. This distinction between mutual and common knowledge has a long philosophical history and has long been well-understood by gossips and inside traders. In modern times the notion of common knowledge has been formalized by David Lewis, Robert Aumann, and others in various ways and its relevance to everyday life has been explored, most recently by Steven Pinker in his book When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows.

I discussed common knowledge in my books Once Upon a Number and A Mathematician Plays the Stock Market and illustrated it with the following parable, which suggests its power.

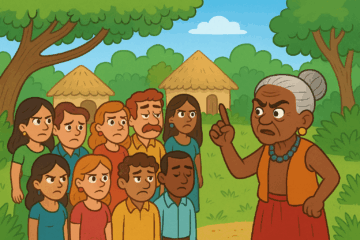

The parable takes place in a benightedly sexist village of uncertain location. In this village there are many married couples and each woman immediately knows when another woman’s husband has been unfaithful but not when her own has. The very strict feminist statutes of the village require that if a woman can prove her husband has been unfaithful, she must kill him that very day. Assume that the women are statute-abiding, intelligent, aware of the intelligence of the other women, and, mercifully, that they never inform other women of their philandering husbands. As it happens, 20 of the village men have been unfaithful, but since no woman can prove her husband has been so, village life proceeds merrily and warily along. Then one morning the tribal matriarch comes to visit from the far side of the forest. Her honesty is acknowledged by all and her word is taken as truth. She warns the assembled villagers that there is at least one philandering husband among them. Once this fact, already known to everyone, becomes common knowledge, what happens?

The answer is that the matriarch’s warning will be followed by 19 peaceful days and then, on the 20th day, by a massive slaughter in which 20 women kill their husbands. To see this, assume there is only one unfaithful husband, Mr. A. Everyone except Mrs. A already knows about him, so when the matriarch makes her announcement, only she learns something new from it. Being intelligent, she realizes that she would know if any other husband were unfaithful. She thus infers that Mr. A is the philanderer and kills him that very day.

Now assume there are two unfaithful men, Mr. A and Mr. B. Every woman except Mrs. A and Mrs. B knows about both these cases of infidelity. Mrs. A knows only of Mr. B’s, and Mrs. B knows only of Mr. A’s. Mrs. A thus learns nothing from the matriarch’s announcement, but when Mrs. B fails to kill Mr. B the first day, she infers that there must be a second philandering husband, who can only be Mr. A. The same holds for Mrs. B who infers from the fact that Mrs. A has not killed her husband on the first day that Mr. B is also guilty. The next day Mrs. A and Mrs. B both kill their husbands.

If there are exactly three guilty husbands, Mr. A, Mr. B, and Mr. C, then the matriarch’s announcement would have no visible effect the first day or the second, but by a reasoning process similar to the one above, Mrs. A, Mrs. B, and Mrs. C would each infer from the inaction of the other two of them on the first two days that their husbands were also guilty and kill them on the third day. By a process of mathematical induction we can conclude that if 20 husbands are unfaithful, their intelligent wives would finally be able to prove it on the 20th day, the day of the righteous bloodbath.

A more familiar rendition of the phenomenon involves three boys who come in from play with mud smudges on their foreheads. They sit down to eat when their mother comments that at least one of the boys has a mud smudge on his forehead. Although this is less than they already know, after thinking through the situation, they all suddenly get up to wash their faces. The explanation for this is the same as that for the murderous wives in the village.

Not a Fantasy

Let’s adapt the above parable to an unfortunately more topical situation involving corruption and scandalous behavior. To that end let’s for the husbands substitute a group of politicians, business people, and celebrities of all sorts, and for the wives let’s substitute the possible miscreants’ supporters – staffs, bosses, donors. The above sort of situation is unfortunately not that unusual, especially since there seem to be more and more insular, self-protective, influential organizations and people that are more accepting of scandalous behavior.

In any case, we can replace the warning of the matriarch with the release of videos, emails, and texts by non-partisan prosecutors during a prime-time press conference. We compare the nervousness of the wives with the anxiety of the miscreants’ supporters, and their contentment as long as their own people’s transgressions aren’t being revealed. Moreover, instead of summarily killing husbands, we’ll substitute the ignominious ending of the miscreants’ careers and perhaps worse, and the gap between the press conference and the resulting angry blowback will take a while for the evidence to be processed, but will be much shorter than 20 days. Finally and arguably only a small number of people in the group who are guilty of this scandalous behavior needs to be revealed for the floodgates to open and drown the others implicated.

The parable and these more contemporary speculations demonstrate what can happen when mutual knowledge becomes common knowledge. In the above corruption case the miscreants involved and their supporters know about the transgressions and who did what, but aren’t particularly concerned about it. Individuals’ knowledge doesn’t spark much outrage within the group or in the outside world until the press conference when everyone will know what everyone knows. It’s no surprise that guilty parties are so often fiercely opposed to transparency. Tiny wink.

Of course, in order to change the logical status of a bit of information from mutually known to commonly known, there must be an independent arbiter. In the parable it was the matriarch and in the mud version it was the mother of the three boys, but the existence of an analog to them in real situations is problematic. If there is no one who is universally respected and believed, the motivating, activating, and cleansing effect of the revelations is lost. That might be an especially acute problem today when powerful forces seem to be working to muddy the notions of facts and truth.

Happily in many cases for an event or a bit of information to become the common knowledge of a group does not require that the group members make any complicated inferences as above but rather it arises naturally when everyone in the group observes the event in question, say by watching a widely televised speech or sporting event, or simply by openly and honestly discussing the event(s) in question.

Still, we could benefit from having more matriarchs. After all, democracy really does die in darkness.

***

John Allen Paulos is an emeritus Professor of Mathematics at Temple University and the author of Innumeracy and A Mathematician Reads the Newspaper. These and his other books are described and available here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.