by Barbara Fischkin

People who have never been to sleepaway camp, don’t get it. They tease me when I speak about memories that are decades old, as if I am recalling a past life that never happened. They find it strange that I view my many years at camp as not merely summer vacations but as forces that helped to make me who I am. These camp memories visit me more deeply when the winter sky sets early, fooling me into believing that 4:30 pm is really past midnight. If I am roaming, I wonder if it is already time to go home. I linger. Yes, my summer camp taught me to roam physically—and in my imagination. It was free and free-range.

I’ll tarry briefly where many good tales begin. In the middle: My teenage years, as a camp clerk and then as babysitter for a camp director and finally, as a counselor. These summer jobs were woefully underpaid. But the fringe benefits were great: Opportunities to break rules that were often not enforced, anyway.

I smoked my first joint, out in the open, sitting with friends on a large rock by the lake, right after a late summer sunset. If caught by a camp director, we would have been fired. I don’t think they wanted to catch us. They were somewhere else, smoking their own joints. Romance, along with pot, seemed to be part of the plan for young employees, particularly in regard to the kitchen boys over whom we swooned. My camp, socialist at its core and run by lefty social workers, did not believe in waiters. To check out a kitchen boy, campers and staff had to go to one of several pantries to pick up or deliver food, plates and utensils. A chore made joyful.

In regard to specific romance, I remember the night I spent with a slightly older male counselor, sleeping with him in his tent—and not doing much more than sleeping. (Maybe it was the pot). Before dawn I shoved him awake and said: “I have to go, I will get into trouble.” He laughed a sleepy laugh, perhaps a stoner laugh and said: “Barbara, this is Wel-Met. Nobody gets in trouble for sleeping with someone.”

He was my crush of the moment and by Wel-Met he meant the Wel-Met camps, three “divisions” in the Catskill Mountain region of New York State. I worked in the Narrowsburg Division that year. Down the road was a privately-owned bar and the Silver Lake Division. The Barryville Division was a bit farther away. Wel-Met, long gone, was once one of the largest camps in the country and it also ran a series of cross-country camping “Western Trips” for older campers. From the year I turned 8 until the summer before my senior year at college, when I was 19, I spent entire or partial summers as a Wel-Met camper or summer job-holder. The entire operation was run by a Manhattan-based non-profit, with offices downtown on Madison Avenue. My mother referred to this non-profit as “The Federation of Jewish Philanthropies.” Like Wel-Met, she is long gone and I can’t find an exact match on the Internet. I do remember finding the corporate name odd, since many rich kids from Long Island were among the campers. Nevertheless, the cost was far lower than most camps. And many other campers, like me, were from the New York City boroughs. Our parents were working class but they could better afford to pay for Wel-Met than a fancy camp. It was no secret that a small number of black campers had come on “scholarships.”

I know of only one famous camper, Howard Stern. I guess the social workers failed with him.

In part-two of my camp memories, I will write more about escapades during my teenage years. For now, I will pick up where all of our lives, if not all of our stories, begin. In childhood.

At eight, my mother thought I was too young to go to sleepaway camp. I begged her to let me go, until she broke down and agreed. I wanted this because my best friend, Robin, was going to Wel-Met: Barryville Division. In those years, I wanted to do everything Robin did. Robin was older than me so I knew we would be in different bunks and in different sections of the camp. I wanted to go anyway. I suspect Robin’s mother, Lila, talked my mother into it. I liked Lila a lot as did my mother— and a few years later Lila also became a role model for me, as the first working mom I knew.

And so, I happily helped my own mother to pack my trunk and duffle bag, over-packed for what would be the three-week session, often chosen by the parents of younger campers. Parents’ visiting day would take place after we were away for a week-and-a-half. What could go wrong?

Three days into my first camp experience, I found out exactly what could go wrong. I got homesick. Very homesick.

I was very close to my parents. I had a doting brother. But he was 12 years older and left for college as I started first grade. From then on, I was mostly raised as an only child. At camp, I quickly learned how connected I was to my parents. On that third day at Wel-Met an awful wave of loneliness splashed over my whole body. It was a new pain. I had never felt this sad. It happened during breakfast in that huge camp dining room run by the kitchen boys, who back then were the last thing on my mind. In my mind’s memory, the dining room looked more like a prison mess hall, although one filled with laughing children.

Except the ones, who like me, were homesick.

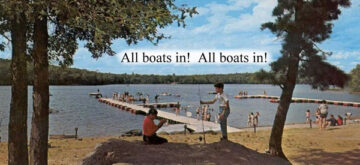

I don’t know what the other homesick kids did at first. But, not knowing what else to do, I muscled through with that sadness, through my activities until the after-lunch rest period. (It was our counselors who needed the rest). That’s when I decided to write a letter to my brother, whose summers were spent as a counselor at another camp. I wrote: “Ted, I am homesick. Please do not tell Mom or Dad. I don’t want them to worry.” Mind you, this was about a week before Parent Visiting Day. I laugh now at the timing. But the pain I felt was so real. And yet, something compelled me to keep this a secret from my parents. Perhaps I was trying to save face. Maybe my mother had been correct. Maybe I was too young. Maybe she should not have given in to my begging and Robin’s mother’s reassurances. Or maybe it was the Wel-Met atmosphere where in a loving way, campers were encouraged to think for themselves. The camp, in keeping with its persona, did not have horses, tennis courts or swimming pools. Just a muddy lake with canoes and small sailboats, some arts and crafts shacks and campfires, where counselors played their own guitars and led us in folk songs.

What it did have, though, was a “Homesick Club.”

My brother wrote right back. “I am very proud of you. I will not tell Mom or Dad.” By the time that letter arrived I already had been sent to the “Unit One Homesick Club.” My first experience with the value of talk therapy. I remember being asked if I wanted to go to the Homesick Club. I was not told that I had to go. Crying and not knowing what else to do, I went. At the first meeting a counselor, perhaps a camp director, named Leon or Leo, greeted us with kindness. I remember him being pale with reddish hair, sort of ethereal with a touch of fire atop his head. Each homesick camper had a chance to talk, to share stories about how afraid and sad we each had suddenly become at camp. There was something in each story that sounded like my own. Within days I felt better. “I don’t feel homesick anymore,” I told Leon/Leo. “You have graduated!” he replied. My counselors kept an eye on my emotional state for a few days and by the time my parents showed up for visiting day I had a “diploma,” to prove I had graduated from the “Unit One Homesick Club.” I showed my parents my diploma and told them everything. They nodded, smiled. Probably, they already knew. Now I wonder why all therapy can’t be this easy.

After my parents went home, back to Brooklyn, I carried on with the last week and a half of camp, never realizing that my connection to Wel-Met would go on for years. One evening, we packed up sleeping bags and slept in the surrounding woods after cooking over an open fire. We might not have had tennis courts. But we had choices aplenty. And encouragement to make our own choices. We sat on the grass with our bunkmates and made our own schedule of activities from a list of what was available at certain times. We picked our own individual “hobbies.” (Mine was dramatics, which in retrospect seems hysterically appropriate). We were not pushed to take deep water tests in the lake but rather encouraged to try out for the deepest water, with counselors standing nearby holding bamboo poles to rescue us. We were urged to make our own fun, during “schmooze” time after dinner and before the evening activity. During this hour we could do whatever we wanted. Visit friends, play ball or sit in our bunks and read comics, or books—or think. I did it all.

Endnotes: I am also writing this now, in the dead of winter, because two people, camp people, are on my mind. One is Paul Cullen, who died last month and was a legend in his own time, as the director of a very different kind of camp, one for developmentally disabled and autistic children and adults including my elder son. A camp, with far more challenges, than a homesick little girl. Yet Paul’s Camp Loyaltown had the same values as Well-Met. It presumed competence and it offered choices.

The other person who comes to mind as I write about camp is Oksana Fuk. I have written about her a few times, mostly about her life in Ukraine, as war rages. Oksana was among a number of Eastern Europeans recruited by Paul Cullen years ago—to be Camp Loyaltown counselors. Now, she lives in her hometown, Ternopil, Ukraine and is a mother and a college administrator. Since the invasion three years ago we have checked in with one another, by email, several times a month. She writes about her efforts to help, educate and train internal refugees and returning soldiers. Ternopil, in the west of Ukraine, should be relatively safe. It isn’t.

From Oksana’s most recent email: “We were attacked and this is the apartment building near my parents.” She attached a photo of a destroyed, burned-down structure… “Crazy night. No safe place in Ukraine these days, unfortunately.” Her words reminded me of the folk songs my Wel-Met counselors would sing around the campfire, strumming their guitars. Vintage songs and new ones, written and/or performed by Joan Baez, Woody Guthrie, Phil Ochs, Buffy Saint-Marie, Pete Seeger and others. I still hear the lyrics. Words like Seeger’s: “I’m gonna lay down that atom bomb/Down by the riverside down by the riverside/Down by the riverside/ I’m gonna lay down that atom bomb/Down by the riverside study war no more.”

And words from an old German song, sung by those who resisted Hitler. Its title “Die Gedanken Sind Frei,” means “thoughts are free.” These are its lyrics translated, as I first heard them in camp as an eight-year-old: “My thoughts will not cater/ To duke or dictator/No man can deny/Die Gedanken sind frei!/And if tyrants take me/And throw me in prison,/My thoughts will burst free/Like blossoms in season/Foundations will crumble/The structure will tumble,/And free men will cry/Die Gedanken sind frei!”

Remembering these lyrics in these times is why for me camp matters, even—and perhaps especially—in the dead of winter.