by Mark Harvey

Slaughterers of ideals with the violence of fate

Have cast man in the darkness of labyrinths intricate

To be the prey and carnage of hounds of war and hate.

–Ruben Dario, Nicaraguan Poet

Between my junior and senior years of college, I spent part of a summer in Costa Rica studying Spanish in the capitol city of San Jose. This was 1987 when the war was still going on in neighboring Nicaragua between the Sandinistas and the Contras. I met a young Texan studying Spanish at the same school and he and I hit it off and became friends. We were both interested in the war going on in Nicaragua and decided we’d fly up there for a few days to see what was really going on. On the day we were supposed to fly from Costa Rica to Managua, my friend called me and said he had decided not to go. I had a moment of hesitation, but having bought a plane ticket and very eager to see Nicaragua I decided to go on my own.

As our plane descended into the Managua airport, I saw a lot of military vehicles along the runway and began questioning my judgment: Americans were, after all, giving military aid to the Contras, the army fighting the newly established government under Daniel Ortega. Why on earth would the customs people let me into their country? But they did.

At the time visitors were required to exchange about $400 US for Nicaraguan currency and that amounted to a huge cellophane-wrapped package of Nicaraguan bills. In those days with the war going on, there was no easy way to line up lodging or transportation, so I walked out of the airport on a dark night with a huge package of currency in my hands and no idea where I was going to spend the night.

There were a few very beat-up cars outside the airport picking up passengers on an underground system of taxis. I got into the first one in the line, a large American Oldsmobile with a windshield patched in so many places it resembled a Moroccan tile mosaic. My Spanish at the time was intermediate but I was able to explain my situation to the driver and my need for a place to stay.

He said he knew an old man who lodged people in his house illegally and would take me there. It was already night and we drove through the battered streets of Managua for about 20 minutes. During the drive I again questioned my judgment: I had a huge wad of cash, no place to stay, middling Spanish, and was entirely at the mercy of the taxi driver. My cash would have bought him a nice new windshield with money to spare for food. But the driver took me to a modest single-story house in a neighborhood whose name I can’t remember and introduced me to the owner.

The owner had to have been in his late seventies, a thin strong-looking man with a crew cut and glasses. He took my bag, hurried me into his house and proceeded to make this misplaced gringo feel safe and welcome in his modest home in a war-torn country. The rental price we agreed on was about $10 per night.

His house was spotlessly clean, but it was obvious that the basics of a lodger—sheets, pillowcases, towels—were in short supply and that he hadn’t had the means or the opportunity to buy new ones in quite some time. His towels and sheets were very clean but literally threadbare.

After settling in, he poured me a small glass of rum and we sat on a patio on the back of the house to chat. I told him my situation and he didn’t seem fazed at all by my somewhat reckless decision to explore the war-torn country on my own.

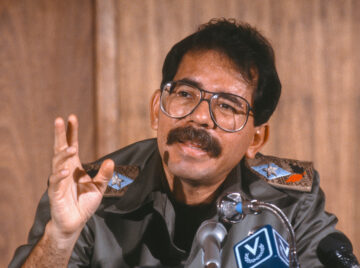

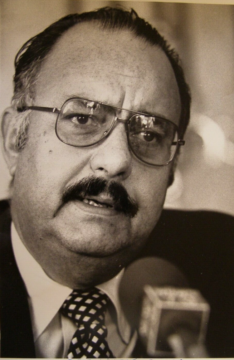

At the time I was a supporter of the Sandinistas. The president of Nicaragua at the time was Daniel Ortega, a young bespectacled man, who had shown indisputable bravery as a guerilla fighter since his teen years. Daniel and his two brothers Humberto, and Camilo had helped lead a revolution against Anastasio Somoza, the brutal dictator who had served as president of Nicaragua from 1967 to 1979. The Somoza family had been in power for more than 40 years beginning with the father, also named Anastasio, in 1937, moving to one of the sons, Luis, in 1956, and continuing with the younger Anastasio in 1967 when Luis died.

The Somozas were not nice people. The saying, “He may be a son of a bitch, but he’s our son of a bitch” is attributed to Franklin Roosevelt talking about the elder Anastasio Somoza. The same Somoza came to power after a long war against rebels led by Augusto Sandino, for whom the modern Sandinistas were named. It took a little extra work to officially become president, including assassinating Sandino shortly after “peace talks” and organizing a coup to take down his wife’s uncle in 1936.

Somoza was officially declared president of Nicaragua in 1936 after winning an election with 107,201 votes to 100. Now that’s a landslide and only a cynic would suspect any fraud with those margins!

The list of the Somoza family’s acts of corruption and murder could fill a library in Managua but they were a family that literally profited off of blood money. In the early 1970s, a Cuban exile named Pedro Ramos started a business called Plasmaferesis that collected blood, and sold the blood plasma worldwide. Built on land in downtown Managua owned by Somoza, the blood center was for a few years the largest plasmapheresis operation in the world. At its peak, Plasmaferesis collected the blood of up to a thousand people per day. Donors were paid about $1.25 per half liter and the center attracted the most down-trodden of the Nicaraguan population.

“Every morning the homeless, drunks, and poor people went to sell half a liter of blood for 35 (Nicaraguan) cordobas,” according to La Prensa journalist Roberto Sanchez Ramirez

The Somozas also owned hundreds of farms amounting to about 60% of Nicaragua’s arable land. With strong ties to West Point and the United States, the family had influential friends in the US Congress and the support of administrations from Franklin Roosevelt to Richard Nixon.

Sipping rum on the patio my first night in Nicaragua and hungry to learn as much as I could, I asked the old man his opinion on the war. He was crystal clear in his opinion: the Sandinistas were destroying his country. This took me aback a little as from afar I had sugar-plum images of the Sandinistas uniting Nicaraguans hungry for freedom. But my host had a long and considered litany of the many things they were doing wrong.

I had been studying a lot of Latin American history at the time and what I read about the lands from Mexico to Tierra del Fuego suggested a long line of dictators, military and civilian, who had pretty much crushed democracy with ruthless efficiency. My world view was pretty simplistic as is typical of young people and I was quite ready to divide the world into good and evil. But with Somoza it wasn’t difficult: he was just plain evil.

The next day I took my knapsack and camera and began exploring Managua on foot. There was no fitting in, and I didn’t even try. There were military vehicles and soldiers everywhere. Open-backed stock trucks filled with Sandinista soldiers ripped through the streets kicking up dust. Other trucks carried Contra prisoners, captured and headed to prison. There were long lines of people waiting by dispensaries to get basic staples such as milk, flour, and cooking oil.

With what I’ve come to realize was more youthful foolishness than bravery I walked all over town taking photos of soldiers, citizens, buildings, and the lines of hungry people waiting for rations. Many of the soldiers appeared to be very young—some not much older than 16 in my estimation. They all had Soviet-issued rifles and light machine guns and the most exposed I felt was the careless nature with which they wielded their weapons.

The hunger in Managua was impressive and rampant. There were very few operating restaurants when I was there so I took to eating at a little place that, for about a dollar, would serve a person a piece of rotisserie chicken, rice and beans on a paper plate. The food was basic but excellent. I generally eat all that’s put on my plate and in those days with the long walks around the city I would clean the chicken down to the bones. But my first day at the restaurant a small group of young boys came up to me after I had finished eating and gestured toward the remaining chicken bones, asking if they could have them. I said sure, and in a flash one of the boys grabbed the bones and ate them right there in front of me. That happened every day that I ate at that joint.

Managua was a disaster when I was there, not just from the war, but from the wreckage of an earthquake that took place in 1972, 15 years before my visit. Though international aid had poured in to help the country recover from the earthquake, Somoza and his cronies stole most of the money and did very little to help the thousands of people suffering from the damage. At a time when blood plasma was badly needed, Plasmaferesis continued to export most of the plasma taken from Nicaraguans for the high profits earned abroad. Blood money indeed.

Though he didn’t know it at the time, the 1972 earthquake and its aftermath was the beginning of the end for Somoza.

It was hard not to admire Daniel Ortega in his early years as a leader. His first arrest for political activities took place when he was only 15 years old. At the age of 22 he was arrested and jailed for an armed robbery on the Bank of America meant to fund the Sandinistas, and spent seven years in El Modelo prison outside of Managua. When he was released, he was exiled to Cuba where he learned guerilla warfare from Castro’s army.

Ortega was one of the leaders of the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional (FSLN), the organization that eventually brought Somoza to his knees and forced him into exile in Miami. He led a faction of the FSLN called the Terceristas, meaning the third way.

When Somoza was overthrown in 1979, the entire country was ecstatic. Nearly everyone in Nicaragua hated Somoza from the far-left Marxists to the most conservative capitalists. Sergio Ramírez Mercado, once the vice president of Nicaragua when Ortega was president wrote,

The euphoria in the country was complete, and the following day, when the victory was celebrated in the Republic Square, renamed as the Revolution Square, the crowd consisted of people from all social classes who came to celebrate the end of tyranny after so much bloodshed, so much death, and so much destruction.

After Somoza was defeated, Nicaragua was ruled by a Junta made up of five members from various political backgrounds. Three of the members including Ortega were considered leftists, but two of the members, Violeta Barrios de Chamorro and Alfonso Robelo, were businesspeople and considered conservative. The makeup of the Junta was a sincere effort, from my reading, to form a government that represented a broad spectrum of Nicaragua’s political class.

Ortega was elected to be president in 1985 and served until 1990, when he was defeated by Violeta Chamorro. He was elected again in 2007 and according to the Nicaraguan constitution at the time, was only supposed to serve just one five-year term before leaving office. But in 2011, the Nicaraguan Supreme Court declared that the term limits were unenforceable and the term limits were scrapped entirely in 2014. It’s fair to say that Ortega helped with that decision.

Thus, à la Chavez in Venezuela, Putin in Russia, or, drum roll, Somoza before him, Ortega has been president for sixteen years now, with no end in sight. And in those sixteen years, Ortega has drifted ever closer to becoming just another corrupt dictator like the one he fought so valiantly to defeat as a young man.

In 2017 he appointed his wife, Rosario María Murillo vice president of Nicaragua (what could possibly be undemocratic about that?). The two have ruled Nicaragua with an iron fist, imprisoning their critics with Orwellian-like charges such as “Conspiracy to Effect Diminishment of National Integrity.”

What really rattled Nicaragua and the international community began in April of 2018 when students took to the streets to protest planned reductions in social security payments along with increases in payroll taxes. Over the ensuing months, there were several more demonstrations involving hundreds of thousands of people protesting Ortega’s regime.

What really rattled Nicaragua and the international community began in April of 2018 when students took to the streets to protest planned reductions in social security payments along with increases in payroll taxes. Over the ensuing months, there were several more demonstrations involving hundreds of thousands of people protesting Ortega’s regime.

Ortega’s police cracked down hard and by July more than 300 people were killed with thousands injured. 2018 was a year in which Ortega’s regime would have been the envy of the late Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet. His repressive, violent measures earned worldwide criticism. In what holds great irony, Chile, now long rid of Pinochet and far more democratic than Nicaragua was the most critical Latin American nation.

Ortega has arrested several of his former comrades including the septuagenarian Hugo Torres who fought with him as part of the FSLN back in the 1970s and 1980s. Torres died in prison last year. The regime put several prominent opponents in solitary confinement, including Dora María Téllez, who was a comandante in the FSLN and fought alongside Ortega in the 1970s.

This year, Ortega revoked the citizenship of more than 300 Nicaraguans, some of them prominent intellectuals and writers; some of them former comrades in arms. The list includes Sergio Ramirez, the writer who played a key role in the early success of the FSLN, and was once a friend of Ortega. Ramirez, now 81, recently wrote a novel called Dead Men Cast No Shadows, a thinly disguised portrayal of Ortega’s regime. The book was of course banned and Ramirez now lives in Spain.

“Of what was then, nothing remains,” Ramirez said recently. “The old revolutionary dream turned into a nightmare of ruthless repression.”

Last year, Sheynnis Palacios, a stunningly beautiful woman crowned Miss World Nicaragua in 2020, won the 2023 Miss Universe competition. It was the first time in the country’s history. Palacios has this oversized charisma, youthful swagger, and broad smile. It would have been hard to pick anyone else to win the pageant. In what was a triumphant moment for the country, thousands of Nicaraguans took to the streets to celebrate.

But the vice president and wife of Ortega, Rosario María Murillo, managed to throw shade on the win, accusing the country’s revelers of using the pageant victory to overthrow her little dictatorship. She issued a statement that read in part,

We see the rude taking advantage and the rough and evil terrorist communication that pretends to turn a lovely and well-deserved moment of pride and celebration into a destructive coup d’état mentality. Or a turning the clock back, which is impossible, to the unfortunate, egotistical, and the criminal practices of those who, as vampires and opportunists, have used the people.

The ultimate killjoy—but with an army, a stacked judiciary, and prison cells.

La Prensa Grafica, an El Salvadoran magazine, has a story of Murillo’s bitterness with the Miss Universe celebration. At the top of the story, there is a photo of Sheynnis Palacios next to Rosario Murillo. The juxtaposed photos inadvertently capture Nicaragua’s current state. Murillo’s bitter visage represents an old, tired regime desperately clinging to power; Palacios’ regal image represents what Nicaragua could be—wants to be. The bitter stepmother of Ortega’s regime and the youthful Cinderella or Snow White of a tropical land.

The Czech author and playwright Václav Havel wrote, “Individuals can be alienated from themselves only because there is something in them to alienate. The terrain of this violation is their authentic existence.”

Nicaragua has its modern Son-of-a-Bitch, but he’s not ours, nor should we want him. Daniel Ortega did what so many revolutionaries before him and since have done: he became a revolutionary sellout, resorting to the same sort of iron-fisted grip on power as the very regime he fought to oust. If his days as a young man fighting Somoza were heroic, his twilight years as a bloated old man, murderous and corrupt, are craven, pathetic, and tragic.

Miami awaits your exile, Señor Presidente. Y tu mujer tambien!