by Mark Harvey

Let America be the dream the dreamers dreamed—

Let it be that great strong land of love

Where never kings connive nor tyrants scheme

That any man be crushed by one above.

—Langston Hughes

The years from 1930 to 1945 were some of the most trying times in American history. Our forebears suffered close to ten years of The Great Depression and then, with next to no pause, were thrust into five years of World War II. It’s no wonder that so many men and women of that generation who survived those struggles came away with a quiet stoicism and other-worldly courage. I have a nostalgia for a time I never saw because I knew many of the people who were shaped by those times, and I miss them.

George Orwell said, “Each generation imagines itself to be more intelligent than the one that went before it, and wiser than the one that comes after it.” That’s one affliction I don’t suffer from. I consider the generation that weathered The Great Depression and World War II to be, for the most part, a cut above any generation since. I don’t think it was necessarily their innate character, but rather their mettle shaped by the age.

Having read a number of letters written to the White House during The Great Depression (from a wonderful collection in Down and Out in the Great Depression: Letters from the Forgotten Man by Robert S. McElvaine), I know that the times led to much bitterness and suffering. How could it not? But a tender humility and reserve also runs through much of the correspondence. Many of the writers address the president or first lady as if they were intimate family who might somehow wrangle them a job or free them from their desperate situation. One thirty-one-year-old woman expecting a baby writes,

Dear Mrs. Roosevelt: I know you are overburdened with requests for help and if my plea cannot be recognized, I’ll understand it is because you have so many others, all of them worthy…. We thought surely our dreams of a family could come true. Then the work ended and like “The best laid plans of mice and men” our hopes were crushed again.

A widow with a fourteen-year-old son writes to Eleanor Roosevelt asking if she has a spare coat to get through the winter and even offers to pay for postage if the first lady will send her one. A woman with seven children and just sixty-five cents to her name writes to Franklin Roosevelt asking for help to feed children too proud to beg for lunch.

In reading these letters, it’s clear that many of the writers truly believed Eleanor or Franklin would actually send them a winter coat or give them a job.

The economic numbers from The Great Depression were brutal. In 1933, the unemployment rate hit 25%. For the lucky ones with jobs, wages were cut by more than 40% between 1929 and 1933. It was a decade when people in a rich land were literally starving and threadbare.

As if to add misery to an already collapsing economy, the men and women living in the central and southern Great Plains during the 1930s suffered from nearly ten years of drought in what was called The Dust Bowl. From Texas to southern Colorado and from New Mexico to Oklahoma, the rain stopped and the ground dried up. In some years, the region received as little as 50% of normal rainfall. Crops failed, farms were foreclosed, and a great train of jalopies filled with all the family possessions set out for the promised paradise of California.

But the 1930s were also a time of American glory. For it was the 1930s when men in mid-town Manhattan built the Empire State Building, by far the tallest building in the world. In just one year and forty-five days, 3,500 men put together a building that climbed 1,200 feet into the sky and redefined New York’s skyline.

Over five years, men and women in the scorching desert of Nevada built the colossal Hoover Dam with curves and engineering so elegant that it still looks futuristic to this day. The dam was completed two years faster than was planned and the project came in under budget. While the southern Great Plains were going dry, the Hoover Dam helped “make the desert bloom” in the Imperial Valley, where we get most of our winter produce to this day.

On the West Coast, scrappy builders strung cable and erected steel to build the Golden Gate Bridge, completed in 1937. At the time, it was the longest suspension bridge in the world. It was another engineering marvel constructed ahead of schedule and under budget—two terms that seem to be of a bygone era. With the strong tidal currents and the harsh weather, the bridge’s completion represented another national victory.

While millions of Americans were made penniless, homeless, and demoralized by a failing economy, the grand structures engineered and then built with such savvy had to have been great symbols of hope and deliverance. In imagining those trying times, one can only imagine. But I picture an Oklahoma farmer in the midst of the Dust Bowl seeing the ruin of his crops and the bankers lurking about with foreclosure and that same farmer reading about the Empire State Building or Hoover Dam. And for an Oklahoma minute he forgets his problems and thinks all will be right with the country. The woman with seven children and sixty-five cents in her savings sees what her countrymen in California do to span San Francisco’s Bay and maybe it gives her a moment of reprieve.

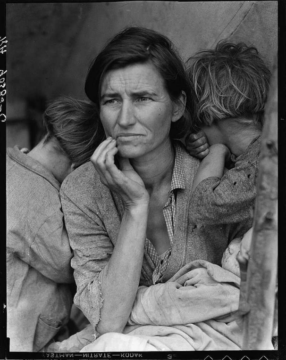

The photographer Dorothea Lange captured so much of that era with her Graflex camera, rambling about the country under the Farm Security Administration program. Many of her photos show a people beaten down by the dust, hunger, and months and years without work. But there is something entirely noble in her photos. Perhaps her most famous image, Migrant Mother, shows a young woman in tattered clothing holding an infant. In the same photo, two young children, with their faces hidden, press against the woman’s shoulders as if seeking shelter. The woman appears to be looking into the distance and lost in worry or thought. I guess you can read what you want in the photo, but what I see is a mixture of anxiety, love, and courage. Lange and other photographers in the FSA program captured Americans living on the thinnest of margins but with some ethereal bit of hope—a trust in providence.

While the Hoover Dam may have been a symbol of hope during the 1930s, the dam’s namesake, President Herbert Hoover, who was president from 1929 to 1933, is mostly linked to the failures during the Great Depression. To be sure, the initial collapse wasn’t Hoover’s fault, but his actions and inactions when the Depression really got going aggravated things. One of his worst decisions was signing the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, which put a 40% tariff on some 20,000 imported goods. Aimed at protecting farmers, the act was met with counter-tariffs from trading partners and U.S. exports fell by some 60% over the next three years. Who’d have guessed that would happen?

American farmers, in particular, got clobbered as their produce was met with the same tariffs overseas. The tariffs also helped make consumer goods more expensive. If you’re thinking that this sounds familiar, remember that history doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.

While writing this, I thought I’d find a real villain in Herbert Hoover as it relates to the Depression, but from what I read, he was a very accomplished engineer, thoughtful, and a humanitarian. He was also a fiscal conservative and a deficit hawk, and he seemed to think America could come out of the quagmire with a sort of nationwide volunteerism.

Hoover wasn’t the right man for the times, no matter his previous accomplishments. And it’s hard to imagine a better team for those times than Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. I mention the two as a team because Eleanor Roosevelt was, in my mind, by far the most effective First Lady in our history and far more effective than many of our presidents.

She dedicated her whole adult life to furthering the cause of the poor, ending racial discrimination, and promoting women’s rights and children’s welfare. There is a long, long list of social programs that might not have succeeded without her tireless work and advocacy such as The Subsistence Homestead Program, the Arthurdale Project, the National Youth Administration, and even The New Deal itself. She crisscrossed the country, visiting coal mines, tenant farms in the rural south, and the dust bowl states of Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas.

There is a long list of quotations by Eleanor Roosevelt that are genuinely profound about American life and life in general. One in particular, written twenty years after the Depression ended, captures both the essence of her life and of her generation. It goes,

Courage is more exhilarating than fear and in the long run it is easier. We do not have to become heroes overnight. Just a step at time, meeting each thing that comes up, seeing it is not as dreadful as it appeared, discovering we have the strength to stare it down.

In writing about this stuff, I can already hear some guy or gal protesting that Americans back then harbored deep prejudices that have since been abandoned. Some of that is true. But judging people of the past based on contemporary values is what’s called presentism. It’s easy to sit in a café and tut-tut about someone from a hundred years ago not sharing all of today’s societal norms, but it’s also snotty. We all try to have individual opinions informed by our values and education, but we also swim in the vast river of the contemporary. A hundred years from now, when Florida is underwater from the rising oceans, our carbon-crazy habits—flying cross country, eschewing mass transit, dedicating vast amounts of electricity to social media—will probably be considered criminal by Americans who have been forced upland into Georgia.

Eleanor Roosevelt came from wealth and could have lived a life of ease. She could have easily spent her time summering in The Hamptons or eating bonbons in a brownstone on the Upper East Side. Her work flies in the face of many of today’s super-rich. One of the great obscenities of our time is the flagrant displays of wealth shown by the likes of Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg, and David Geffen. The combined value of their three yachts is close to a billion dollars. Let that sink in: a billion dollars. I have no admiration for any of the three men, no matter what they accomplished in the business world. To flaunt such extravagance when so many workers live in economic anxiety and on the margins is shameful. It’s a grotesque form of disrespect to those who got them their money with their labor. All three and their like could still live lives of kingly extravagance at a tenth the cost.

When Franklin Roosevelt took office in 1933, he was already bound to a wheelchair from a case of polio. He went to great lengths to hide his disability, and in the pre-television days, that was still possible. America probably needed a man who kept a sunny disposition and panoramic optimism despite having been stricken with a crippling virus.

One has to believe that the stuff needed for a person to forge ahead so valiantly despite his physical limitations might translate into a vision forward for a crippled nation. As only Winston Churchill could have put it, “He brought to his vast responsibilities the buoyant temperament of a Galahad. He was the champion of the common man, and his heart was moved by the sufferings of the underdog.”

Throughout his many “fireside chats” and speeches during the 1930s, Franklin Roosevelt spoke to Americans directly without glossing over the realities of their hardships. He gave them hope when hope was nearly lost. In a 1932 campaign speech, Roosevelt emphasized the importance of the “economic infantry” and said in his second inaugural address of 1937, “The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much; it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little.”

In some ways, we are living in a sort of precursor to a Depression today. The stock market is way overpriced, no matter how you dice it. Employment numbers are strong, but the median American household has about eight thousand dollars in savings. In sum, most Americans are one injury or illness away from bankruptcy. Our president-elect is promising massive tariffs reminiscent of the Smoot-Hawley tariffs created in 1930. The same president-elect has two clowns—Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy—cleaving tightly to his every proposed appointment and giving him fundamentally bad advice. The Bird Flu is showing its feathers in ways that might lead to another health and economic crisis. And the proposed Secretary of Health and Human Services, RFK Jr., probably would have wailed about the polio vaccine that might have saved Roosevelt’s legs had it been developed in time.

In the 1930s, Americans of the Great Plains faced drought and the Dust Bowl, which was terrible enough. What we’re facing today with climate change is a slower process, but the consequences will be much worse. We keep getting tastes of what’s ahead with the wildfires in southern California, floods in North Carolina, and bizarre weather patterns worldwide.

In what can seem a grim future, we desperately need a Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt to thoughtfully lead this country with both their narration and intelligent, forward-looking programs. We need our Galahad. However, we elected a carnival barker who stokes anger and fear instead of encouraging Americans—the forgotten and the vastly wealthy- to unite as one.

It’s no wonder this country is rattling with jangling anger, for anger is usually the mask of fear. Americans are nearly as scared as our forebears in the 1930s, and maybe they should be. But in reading the letters of the forgotten men and women of a hundred years ago, I see a humility and resolution badly lacking in today’s America.

Let us hope that the next few years don’t deliver upon us the very suffering that steeled the generation of the 1930s. May we find what’s best in us by taking a small note from history. May we find what’s best in us some other way.