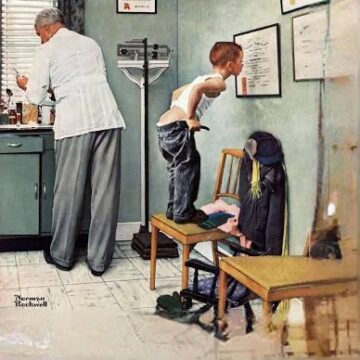

Jacob Lawrence. Migration Series (Panel 52).

Jacob Lawrence. Migration Series (Panel 52).

Casein tempera on hardboard.

“…

Spring, 1968. All my students were black, and I wasn’t. Jacob Lawrence, who was teaching a course down the hall from me at Pratt Institute, was a famous artist and a real teacher; I wasn’t either of those things.

When I introduced myself as a third-year undergrad at Pratt and told him about the Life Drawing class I was offering, Mr. Lawrence smiled. I explained that the college was providing a free model and drawing lessons for low-income adults in the area as part of a program I had helped initiate. “Drawing from a live model is important,” he said.

This highly accomplished man, older and far wiser than me, represented a different kind of model. When I asked if he’d say a few words to my class, his smile broadened. Not surprisingly, he made a big hit that evening, and every evening session thereafter, spending almost as much time in my classroom as he did in his. His eye and mind and storytelling skills were always spot-on. Though I remember him as being too kind to say anything too critical about anyone’s work, my students and I learned a great deal.

…

Lawrence’s series of 60 small, unpretentious panels illustrate the journey of the approximately six million African Americans who migrated from the rural South to the urban Northeast, Midwest, and West in the first half of the 20th century. The dream before them: to secure better opportunities for their families and themselves. They would leave segregation and Jim Crow behind. In Lawrence’s paintings, people work, walk, wait, and die. They gather at train stations, school blackboards, and voting machines, as well as in courts, jails, and funerals. At MoMA, I felt the tensions of the arduous exodus he had heard and read about since he was a child. I felt the artist’s great big ambition to tell a great big story in a way that would allow 8- and 80-year-olds alike to understand and experience it. I felt a peoples’ desperation. I felt Black History in my gut.

The Migration Series (1940-41) was originally shown the year it was completed (under the title Migration of the Negro) at the prestigious Downtown Gallery in New York, marking the first time a New York gallery represented an African American artist. Another first: When MoMA bought half the series (all the even-numbered panels; the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. bought all the odd numbers), Jacob Lawrence became the first African American to have work included in the Modern’s permanent collection.

From: “Mud Above Sky Below: Love and Death in Jacob Lawrence’s ‘Migration Series'”.

Barry Nemett, July 18, 2015.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

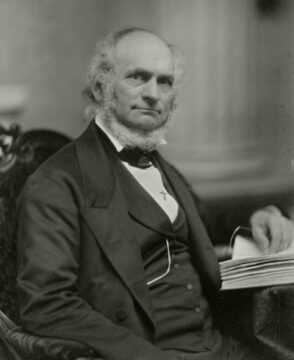

We do not need philosophers to tell us that human beings matter. Various versions of that conviction is already at work everywhere we look. A sense that people are worthwhile shapes our law, which punishes cruelty and demands equal treatment. It animates our medicine, which labors to preserve lives that might seem, by some external measure, not worth the cost. It structures our families, where we care for the very young and the very old without calculating returns. It haunts our politics, where arguments about justice presuppose that citizens possess a standing that power must respect. But what does it mean to say human beings are worthwhile? And why might it be worthwhile to ask what me mean when we say we matter?

We do not need philosophers to tell us that human beings matter. Various versions of that conviction is already at work everywhere we look. A sense that people are worthwhile shapes our law, which punishes cruelty and demands equal treatment. It animates our medicine, which labors to preserve lives that might seem, by some external measure, not worth the cost. It structures our families, where we care for the very young and the very old without calculating returns. It haunts our politics, where arguments about justice presuppose that citizens possess a standing that power must respect. But what does it mean to say human beings are worthwhile? And why might it be worthwhile to ask what me mean when we say we matter? Not long ago I wrote for 3 Quarks Daily

Not long ago I wrote for 3 Quarks Daily  Anyway, I’ve been following

Anyway, I’ve been following

An era of worldwide illiberal governance approaches. If the Trump administration has its way, future illiberal leaders will face fewer opponents. Aspiring autocrats will lose the constraint of the United States as a potential opponent. Autocracy will spread.

An era of worldwide illiberal governance approaches. If the Trump administration has its way, future illiberal leaders will face fewer opponents. Aspiring autocrats will lose the constraint of the United States as a potential opponent. Autocracy will spread. Alia Farid. From the series “Elsewhere”. Produced by Chisenhale Gallery, London. Commissioned by Chisenhale Gallery; Passerelle Centre d’art contemporain, Brest.

Alia Farid. From the series “Elsewhere”. Produced by Chisenhale Gallery, London. Commissioned by Chisenhale Gallery; Passerelle Centre d’art contemporain, Brest.