by Mike O’Brien

About two weeks ago, on October 3rd, news broke that the Net Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA) was no more. The NZBA was one of several business-led alliances convened by the United Nations Environment Programme Financial Initiative (UNEP-FI), with the goal of helping the financial industry to achieve a net-zero carbon footprint by 2050, with interim goals set for 2030. These various alliances (such as the Net Zero Insurance Alliance, which itself died in 2024, and the Net Zero Asset Managers Alliance, which suspended its activities earlier this year) were themselves grouped under the umbrella of the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), founded by UNEP-FI at the COP26 climate conference in Glasgow in 2021 and co-chaired by former central banker and current Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney (in his capacity as UN Special Envoy for Climate Action and Finance), billionaire and erstwhile presidential hopeful Michael Bloomberg (in his capacity as UN Special Envoy for Climate Ambitions and Solutions), and Mary Shapiro, former chair of the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). (Acronym-averse readers are in for a rough ride.) Membership in GFANZ was conditional on a commitment (and demonstrable efforts) to align business activities with the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global warming to 1.5℃ above pre-industrial temperatures.

At its founding in 2021, the NZBA’s membership comprised 42 banks representing about 28.5 trillion dollars. In 2024, membership had peaked at 140 banks representing about 74 trillion dollars. Its insurance equivalent, the NZIA, peaked in 2022 with 291 members representing 66 trillion dollars. How did these initiatives collapse, despite the participation of most of the world’s corporate financial power? American democracy ruined it. More precisely, Republicans gained control of the federal House of Representatives in the 2022 mid-term elections, and signalled that they would investigate companies participating in climate initiatives for anti-trust violations. This emboldened Republican-led state governments to launch their own “anti-woke” intimidation campaigns against financial companies flirting with ecological sustainability. Several Republican attorneys general threatened in 2022 to file anti-trust suits against participating financial institutions, prompting some NZBA member institutions on Wall Street to threaten to leave that alliance unless membership criteria were neutered to placate Republican climate change deniers and fossil puppets (the banks did not use such accurate language in explaining their predicament). GFANZ weakened its requirement that members move to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from their funded activities by 50% by 2030.

This would not, of course, be enough to appease the Republican-represented fossil cartels (to be fair, the Democrats are also quite adept and practiced at representing the fossil cartels’ interests against the interests of American citizens, humanity in general, and all extant terrestrial life). Read more »

Sughra Raza. Under Construction. December 2023.

Sughra Raza. Under Construction. December 2023.

Kazuo Ishiguro often talks about a scene from Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre that has influenced his writing. In an interview

Kazuo Ishiguro often talks about a scene from Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre that has influenced his writing. In an interview  While teaching English at a Yeshiva in the Bronx, I was surprised one day to become part of a theological thought experiment so creative and meaningful that it has stayed with me ever since. After recently learning that the universe may “die” much sooner than previously thought, I recalled that moment as it offered metaphorical depth and poignancy to a scientific truth.

While teaching English at a Yeshiva in the Bronx, I was surprised one day to become part of a theological thought experiment so creative and meaningful that it has stayed with me ever since. After recently learning that the universe may “die” much sooner than previously thought, I recalled that moment as it offered metaphorical depth and poignancy to a scientific truth. On Yom Kippur this year, I went to church.

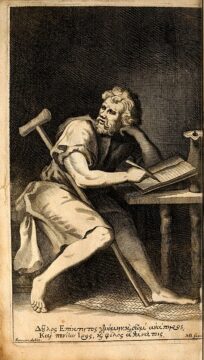

On Yom Kippur this year, I went to church. It feels like I understand the idea that all suffering comes from expectation in a way I didn’t used to. Now it seems so

It feels like I understand the idea that all suffering comes from expectation in a way I didn’t used to. Now it seems so

In Timur Vermes’ best-selling novel Er ist wieder da (‘He’s back’), Adolf Hitler wakes up in Berlin. Somewhat disoriented after discovering the year is 2011, he soon finds his way to the public eye again: he is understandably regarded as a skilled Hitler impersonator, an excellent ironic act for a 21st-century comedy show. His handlers don’t mind the fact that he never breaks character.

In Timur Vermes’ best-selling novel Er ist wieder da (‘He’s back’), Adolf Hitler wakes up in Berlin. Somewhat disoriented after discovering the year is 2011, he soon finds his way to the public eye again: he is understandably regarded as a skilled Hitler impersonator, an excellent ironic act for a 21st-century comedy show. His handlers don’t mind the fact that he never breaks character. The Lakota name for Wounded Knee Creek is Čaŋkpe Opi Wakpala. The first letter is a -ch sound. The ŋ signifies not an n, but nasalization as when you say unh-unh to mean no.

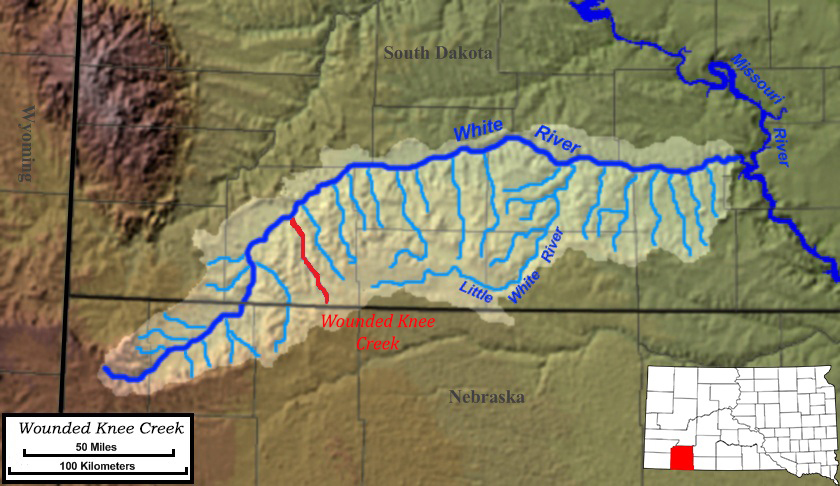

The Lakota name for Wounded Knee Creek is Čaŋkpe Opi Wakpala. The first letter is a -ch sound. The ŋ signifies not an n, but nasalization as when you say unh-unh to mean no.