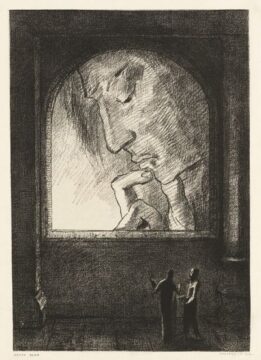

Sughra Raza. Underbelly Color and Shadows. Santiago, Chile, Nov, 2017.

Sughra Raza. Underbelly Color and Shadows. Santiago, Chile, Nov, 2017.

Digital photograph.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

Sughra Raza. Underbelly Color and Shadows. Santiago, Chile, Nov, 2017.

Sughra Raza. Underbelly Color and Shadows. Santiago, Chile, Nov, 2017.

Digital photograph.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Sherman J. Clark

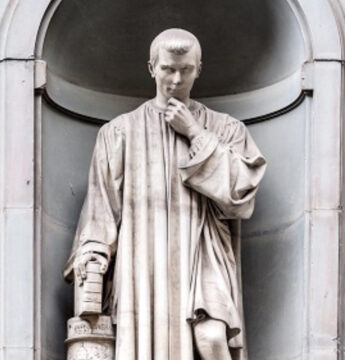

There is no other way of guarding oneself from flatterers except letting men understand that to tell you the truth does not offend you. —Machiavelli

A friend recently described to me his research in quantum physics. Later, curious to understand better, I asked ChatGPT to explain the concepts. Within minutes, I was feeling remarkably insightful—my follow-up questions seemed penetrating, my grasp of the implications sophisticated. The AI elaborated on my observations with such eloquence that I briefly experienced what I can only describe as Stephen Hawking-adjacent feelings. I am no Stephen Hawking, that’s for sure. But ChatGPT made me feel like it—or at least it seemed to try. Nor am I unique in this experience. The New York Times recently described a man who spent weeks convinced by ChatGPT that he had made a profound mathematical breakthrough. He had not.

To be clear: Chat GPT was very helpful to me as I tried to understand my friend’s work. It explained field equations, wave functions, and measurement problems with admirable clarity. The information was accurate, the explanations illuminating. I am not talking here about AI fabrication or unreliability. And in any event, it does not matter whether a law professor understands quantum physics. The danger wasn’t in what I learned or failed to learn about physics—it was in what I was l was at risk of doing to myself.

Each eloquent elaboration of my amateur observations was training me in the wrong intellectual habits: to confuse fluent discussion with deep understanding, to mistake ChatGPT’s eloquent reframing of my thoughts for genuine insight, to experience satisfaction where I should have felt appropriate humility about the limits of my comprehension. I was nurturing hubris precisely where I needed to develop humility. And, crucially, intellectual sophistication does not guarantee immunity. Anyone who has spent time on a college campus knows that intellectual hubris has always flourished among the highly educated. It is hardly a new phenomenon that cleverness and sophistication can be put to work in service of ego and self-deception.

What makes AI different is that it has become our companion in this self-deception. We are forming relationships with these systems—not metaphorically, but in the practical sense that matters. Read more »

by Lei Wang

Lately I have the feeling that everything is speaking to me. This is concerning, not least because there is a family tendency towards mild schizophrenia. As a delinquent intellectual, I have read only a tablespoon of Jung and have never gone to analysis; in fact, I have resisted treating life like literature. I know that not everything is symbolic, that sometimes things happen for no good reason, or at least not any reason that I can claim to know. And yet recently I have been treating everything as a sign: IF the universe were speaking to me, what would it be trying to say?

And I have also been saying back to the universe, “Hey, I got your message!” When the toilet kept running after a midnight flush, disrupting my sleep, I thought it was trying to tell me I had been inconsiderate of my downstairs neighbor, flushing so late. “Thank you,” I said to the toilet. “I got it. Your job here is done.” And immediately the messenger quieted. Yes, every college student knows: correlation, not causation.

But tell that to my Hyperactive Agency Detection Device: what the neuroscientist Justin Barrett calls the part of our nervous systems that is alert for some kind of intelligence beneath reality, probably because once upon a time it was helpful to think the grass moved not from the wind but from something prowling inside it. The Hyperactive Agency Detection Device (HADD) is liberal with giving away a sense of agency. It’s the mechanism by which we attribute essence and personality to our stuffed animals, even if they’re not “real”; it’s how people have AI boyfriends nowadays. Conspiracy theorists have a lot of HADD.

The other day, procrastinating on writing, I was fixing a beloved broken necklace clasp by transferring a clasp from a different, less beloved necklace (I have not gone so far as to believe my necklaces care about this hierarchy). Anyway—a tricky business, having neither pliers nor delicate fingers. I managed three steps in this way, but in the final step, the tiny lobster clasp flew off the desk. I heard it land on the hardwood floor. I swept; I scoured; I was late to my Zoom. I couldn’t find it anywhere in the world on my hands and knees and yet it was everywhere in my consciousness. For hours. My body, which usually finds many ways to be distracted and get itself snacks, had transformed into pure hunter. Read more »

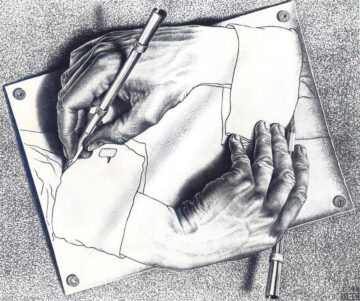

First time I saw Escher’s two hands drawing themselves I thought,

how cool this picture is in its absurd beauty, then much later,

as in now, it comes to me as I give my cognition another chance,

another shot at understanding, more clout in the process of perception,

I think, this is a fundamental truth, a reality truer than the day-to-day

fever dreams of imagination, a truth offering “Eureka!” the word ever followed

by an exclamation point which has just explicitly summed and shattered

the boundary between ignorance and understanding.

There they are, two hands poised with pencils, expressing

the extraordinary, uncomplicated truth that from

cradle to grave we are all drawing shifting renditions

of ourselves.

by Jim Culleny

12/16/25

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Azra Raza

In June 1976, an Air France flight from Tel Aviv to Paris was hijacked by members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine along with two German radicals, diverted to Entebbe, Uganda, and received with open support from Idi Amin. There, the hijackers separated the passengers—releasing most non-Jewish travelers while holding Israelis and Jews hostage—and demanded the release of Palestinian prisoners. As the deadline approached, Israeli commandos flew secretly to Entebbe, drove toward the terminal in a motorcade disguised as Idi Amin’s own and stormed the building. In ninety minutes, all hijackers and several Ugandan soldiers were killed, 102 hostages were freed, and three died in the crossfire. The only Israeli soldier lost was the mission commander, Yoni Netanyahu.

In June 1976, an Air France flight from Tel Aviv to Paris was hijacked by members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine along with two German radicals, diverted to Entebbe, Uganda, and received with open support from Idi Amin. There, the hijackers separated the passengers—releasing most non-Jewish travelers while holding Israelis and Jews hostage—and demanded the release of Palestinian prisoners. As the deadline approached, Israeli commandos flew secretly to Entebbe, drove toward the terminal in a motorcade disguised as Idi Amin’s own and stormed the building. In ninety minutes, all hijackers and several Ugandan soldiers were killed, 102 hostages were freed, and three died in the crossfire. The only Israeli soldier lost was the mission commander, Yoni Netanyahu.

Two years later, I traveled to Uganda myself to visit my parents, who were there while my father helped draft the nation’s new constitution for Idi Amin’s regime. I had no idea that this brief stop in Entebbe would return to haunt me decades later—when, in 2003, I was detained for over five hours at Ben Gurion Airport with my nine-year-old daughter, questioned endlessly about why I had ever set foot in Entebbe at all.

While in Uganda, my siblings and I fell instantly in love with the country—the sheer beauty of the land, the dark mystery of Bat Valley with tens of thousands of fruit bats rising in the evenings as a black cloud from the edge of the city near William Street, the riotous, ever-changing foliage that seemed to reinvent itself every few steps, and the magnificent wildlife we encountered in breathtaking abundance on our unforgettable safari. That trip remains one of the best trips of my life filled with the warmest memories of the country and the people.

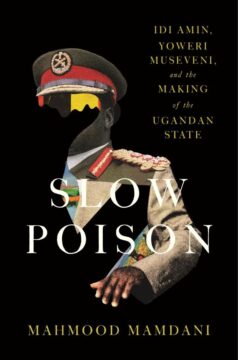

Years later, as I began to understand Uganda beyond my youthful impressions, the work of Mahmood Mamdani offered me a far deeper, more sobering lens—revealing the political currents and historical wounds beneath the beauty we had so casually admired.

What makes Slow Poison instantly gripping is not merely Mamdani’s brilliance as a scholar, but the far rarer gift he brings to this book: the authority of one who lived the history he recounts. Read more »

by Steve Szilagyi

The appetite for Beatles product cannot be sated. Last month, Apple Corps Ltd. released Anthology 4, a new compilation in The Beatles Anthology series, as part of a broader thirtieth-anniversary remastered Anthology Collection. The Anthology series, for those who don’t know, consists of newly mixed outtakes of Beatles songs, previously unreleased tracks, and updated mixes of the two “new” Beatles songs, “Free as a Bird” and “Real Love.” That is 155 tracks of Beatles music presented in alternate versions—versions that are, in most cases, markedly inferior to the originals.

Most Beatles fans already own these songs in their original incarnations on LP, CD, and MP3—along with the many remastered, remixed, reordered, and reissued versions that have appeared since the Beatles’ catalog was belatedly released on CD in 1987. Since then, we’ve had authorized issues of the BBC radio recordings, the failed Decca audition tapes, and the long-circulating Star-Club Recordings. And serious Beatles obsessives have, for decades now, been trading bootlegs: hundreds of alternate takes, studio chatter, Christmas messages, and fan-club recordings.

Yet despite this surfeit, Anthology 4 debuted in the Top Ten on five Billboard album charts. This comes only a few years after the public turned Peter Jackson’s eight-hour Beatles band-practice documentary, Get Back, into a critical, financial, and strategic success for Apple Corps and Disney+. Read more »

by Laurence Peterson

If you have to argue, you’ve already lost. —Unknown

There is so much about the Trump regime that is troublingly peculiar: the base cruelty, the arrogant racism and sexism, the evangelistic ignorance, the fearless disregard for existing law, the super-conspicuous corruption; one can go on and on. What I want to focus on here today is how he, and his toadies and operatives in the administration, lie to all of us. As I shall try to explain below, the intention underlying the lies can vary somewhat depending on the part of the population being addressed at any given time, but one feature seems to stand out in almost all of the messaging: the content of the communication is not as important as the expression or implication of possible contempt for the recipients of that content.

Just in the last few days, Trump has escalated the military buildup off Venezuela to such an outsized point that it is rather clear that an attempt is being fostered to instigate a commission of some kind of rash mistake (by either side, with only the slightest degree of plausible deniability) that will result in hostilities between Americans and Venezuelans (or Colombians), which would then result in a manufacture of consent amongst the American electorate to tolerate a more vigorous attempt at regime change than they seem to be willing to countenance right now. It is also evident that there are other forces in the administration pushing in other directions, and that Trump enjoys playing them off against each other, but commitment to the first component appears to be the dominant component of Venezuela policy. Whatever the outcome of the jockeying, the Trump stance has (until very recently) been consistently expressed as an attempt to combat the importation of illegal drugs into the United States, especially fentanyl and cocaine, despite the demonstrated fact that Venezuela plays at best a very minor role in the trafficking of either drug to the US. In the very midst of all this, Trump pardoned the ex-President of Honduras, Juan Orlando Hernandez, who was convicted by a US court (and imprisoned there), of, you guessed it, trafficking 400 tons of cocaine into the US. Hernandez is even alleged to have said “We are going to shove the drugs up the noses of the gringos, and they won’t even know it.”

Also in the last few days, The Guardian reported that Trump owned two mortgages he claimed were primary dwellings, the very charge that Trump directed his Department of Justice to (unsuccessfully) indict former New York City prosecutor Letitia James on. James, it will be remembered, was the prosecutor who in 2022 filed a civil suit against Trump that resulted in penalties and a fine of four hundred million dollars (which was later voided as excessive; James plans to appeal this).

I have chosen these incidents as illustrative of my contention because they are so obviously contradictory and involve actions so hypocritical that it is impossible, if one is paying any attention to them at all, to avoid a conclusion that Trump and his administration have absolutely no respect for the recipients of this information, or that they are at all concerned about any possible consequences of presenting such blatantly offensive duplicity as its modus operandi to innumerable multitudes of citizens. They are, in the most direct way, putting up the biggest of middle fingers to the very ones they took an oath to serve and protect. How is this possible? What does it mean that we have come to this absurd point? Read more »

by Carol A Westbrook

Who can remember back to the first poets,

The greatest ones,…so lofty and disdainful of renown

They left us not a name to know them by —Howard Nemerov, The Makers

In this poem, Howard Nemerov, Poet Laureate from 1988-1990, reminds us that we have no idea when poetry—that is speech—began. The origin of speech is lost in the depths of prehistory, but archaeologists are working hard to get a better understanding of how speech began, because it is one of the few things that makes us unique as human beings.

Social animals communicate in order to coordinate activities, share resources, and improve their chance of survival. There are many examples of animals communicatio: bees, for example, do an elaborate dance to tell others where they found food; whales and elephants also exchange information and coordinate activities. But humans are the only animals that communicate by speech.

At one time it was thought that closely related animals like the great apes, chimps and bonobos would be capable of speech if only they were raised like human babies. There were several attempts to do this by raising young chimps in human families and monitoring their acquisition of language. But while these chimps learned to understand some human speech, they fell far behind their human brothers and sisters in vocalizing more than a word or two. They never learned to speak properly more than a few words, and it soon became apparent that these apes must have been lacking certain anatomic features that were present only in humans.

Scientists have a fairly comprehensive understanding of the evolution of the human species, supported by the fossil record and DNA studies.

As seen on the picture on the right, our likely earliest ancestor is called Australopithecus, and is thought to have existed about 3.4 million years ago (mya).. The term Hominid (Family Hominidae) includes all great apes including humans (orangutans, gorillas, chimps, bonobos, and us) while hominim (Tribe Hominim) is a narrow group within hominids, referring specifically to modern humans, our extinct ancestors, and all species more closely related to us than the chimpanzees, after our evolutionary split from chimpanzees. After Australopithecus came homo habilis, the maker, who made and used stone tools. Next came homo erectus, who used fire; then came Neanderthal and Homo sapiens, two species who evolved from a common ancestor. At what point did speech arise? Read more »

by Dilip D’Souza

On a stargazing trip between September 19 and September 23 this year, I spied a supernova.

Well, not quite. I took plenty of photographs of a spectacular night sky through the four nights I spent out in the open. Then I came home and looked through them, still filled with wonder at what I had captured. Then I read some astronomy news. Then I returned to my photographs and looked through again, this time in some frantic urgency.

Then I had to (figuratively) sit down. For there it was. The supernova. In my photograph.

That is: On September 23, there was news that an amateur astronomer in Australia, John Seach, had discovered a supernova in Sagittarius two days earlier. In fact, and astonishingly, he had discovered two supernovae on successive days. The brighter of the two was only visible in the Southern hemisphere. But the other one was in the constellation of Sagittarius. Because I had pointed my camera at the Milky Way so often through my trip, Sagittarius was in several of my photographs.

I pored over all of them. I had several images from before September 21, and several more from after. All I needed to do was find a dot in a post-September 21 photograph that wasn’t there in a pre-September 21 photograph. You might wonder how, in images with thousands of dots – that’s how spectacular the night sky was – I could even think of finding a specific one. But the report from Australia had an image locating the supernova just “below” Sagittarius. So I knew pretty much exactly where in my photographs to look for it.

And to my amazed delight, I actually did find such a dot, precisely where I expected it. There on September 22. Not there on September 20. The supernova, on my laptop. Read more »

by David J. Lobina

‘…a los gritos de «¡Viva España!» «¡Viva La Legión!» muere a nuestros pies lo más florido de nuestra compañías…’ —Franco, Diario de una Bandera [i]

In these times in which the term ‘fascism’ is forever abused, especially in the English-speaking world, and more specifically in the US, where large swathes of the liberal intelligentsia have convinced themselves that they are living through actual fascism,[ii] it is perhaps inevitable for the hispanist historian Paul Preston to be asked, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Francisco Franco’s death, why he is not so keen to call Franco a fascist (and, by extension, Francoist Spain a fascist state). And a historian’s answer he provides (not my own translation, because I am lazy, though I have edited it; my emphasis):

The use of the word “fascist” is a problem for me. If you ask me what a fascist is, I would say that the clearest example is Mussolini’s Partito Nazionale Fascista. Everything else is different. The problem with the word is that it is used as an insult. Today we say that Trump is a fascist. But of course, I am a university professor, and when I was at Queen Mary, University of London, I taught a course on the nature of fascism where I always asked to what extent Nazism was a case of fascism, because the problem is that it is something much worse. And Francoism, in many ways, was also worse.

Furthermore, [Italian] fascism had a rhetoric of doing away with everything old, something that Franco did not have, as he supported large landowners and the aristocracy. The part about the violence, which many associate with fascism, comes in Franco’s case from being a colonialist military man, an Africanist. Without Africa, I don’t understand myself, he said. Just like the Belgian or British military of the time. That’s why I’m uncomfortable using the word fascist with Franco.

This is par the course for a historian, as I have stressed many times before at 3QD (see, for instance, this piece) – most historians of Fascism, Nazism or Francoism have always kept them quite apart conceptually, despite some prima facie clear commonalities, which seem to me to be overemphasised in general anyway.[iii] But no more of this argumentative line now.

More to the point of this series, and as the Preston’s quote alludes to, it is Franco’s experiences in North Africa that explain a great deal of both his own outlook and that of the milieu he surrounded himself with – and this is a better foundation to understand Francoism than any analogies to Italian Fascism, let alone Nazism. Read more »

by Mike Bendzela

In “Hawthorne and His Mosses,” Herman Melville’s effusive review of the Massachusetts writer’s collection of short tales, Mosses from an Old Manse, Melville utters, under a cloak of anonymity (“a Virginian Spending July in Vermont”) one the most homo-erotic bits of praise imaginable for another male writer: “[He] shoots his strong New-England roots into the hot soil of my Southern soul”! Reclining in his Vermont “hay-mow” with Hawthorne’s volume, the smitten Virginian notes “how magically stole over me this Mossy Man!” Indeed! Melville knew of what he spoke — of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s stories, that is, many of which have become classics, such as “The Birth-Mark” and “Young Goodman Brown.”

I mention all this not just because it’s awesome but because I want to pilfer Melville’s torrid statement to say this of Southern old time music:

“It shoots its strong Appalachian roots into the chilly soil of my Northern soul”!

I use Clifftop here as an avatar for this last essay excursion into how the culture of the American South has had a life-changing effect on me: Its myriad old time tunes have possessed me for about twenty-five years now. Clifftop, West Virginia is the location of Camp Washington-Carver, site of a yearly festival of old time fiddle and banjo music, the Appalachian String Band Music Festival. This festival is rustic, acoustic, genuine, low-tech, and — happily — takes place on top of an actual doggone 2500-foot hilltop, surrounded by dense deciduous forest. I’ve been to this mecca of old time only twice, the two trips twenty-two years apart, for a total of about seventy hours of non-stop jamming; but it’s effect on me has been profound, sort of like Saul of Tarsus seeing the Risen Christ, or something like that. Read more »

by Peter Topolewski

Before the violence in the movie Bugonia moves center screen—and the narrative takes a not completely unexpected left turn—it’s made clear Teddy’s paranoia and consuming conspiracism and violent nature all have roots in childhood trauma. Things like child molestation and the hospitalization of his drug addled mother.

Oh gawd, you think, another movie explaining away awful behavior with a hellish upbringing. Seen it a million times, it’s boring already.

Boring in a movie, maybe, but that’s real life. Except it’s not only trauma that explains rotten behavior. Everything up to this moment in time explains everything about you, everything you’ve done, you’re about to do, and ever will do. This according to Robert Sapolsky, neuroscientist and author of Determined. You have no free will, your actions are determined by your genes, your environment, and your experiences. You have control over none of them.

His book, a couple years old now, has been well reviewed and discussed right here on 3 Quarks Daily, and there’s no need to do so again. The book feels like a mess at times, but an enjoyable one. And the choices—yes choices—Sapolsky made while writing the book are fascinating, the details of the science both enlightening and staggering, his purpose for writing it never more vital. And the implications are a trip. There’s no reason to carry on with this, but I have no choice but to go on, no more choice than I had to stop reading Determined, no more choice than Sapolsky had writing it.

Did he write it? Read more »

Car in a parking lot with frost on the ground.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Mark Harvey

The dark power at first held so high a place that it could wound all who were on the side of good and of the light. But in the end it perishes of its own darkness… —I Ching, #36, Ming

Years ago, someone gave me a copy of the I Ching, Book of Changes, translated by Richard Wilhelm. It’s a heavy little brick, more than 700 pages, and bound with a bright yellow cover. When I received the gift, I looked at it skeptically and never expected to read it. To my surprise, it’s been with me ever since, I’ve read it dozens of times, and the spine of the book is sadly broken from too many readings.

I grew up in a family with fairly skeptical parents and some very skeptical siblings. I vividly remember asking my parents if Santa Claus was real at an age when parents should definitely not disillusion a child of that belief. My parents looked at each other with pained expressions and then, too honest to lie about it, tried to let me down gently. So nothing in my formative years prepared me to like the I Ching.

Not all I Chings are equal, and there are some pretty flimsy versions out there. There’s even an app called I Ching Lite. Of the English versions, the Wilhelm/Baynes translation is one of the most respected.

The I Ching is said to be almost 3,000 years old and originated in China’s Zhou Dynasty. The structure consists of six stacked lines (called hexagrams), each either broken or unbroken. You’ll remember from your high school math that if you have two binary options (broken or unbroken) on six lines, you end up with 64 possible combinations. And that’s what the I Ching looks like: 64 hexagrams, each with its own special meaning. Read more »

by TJ Price

I came to Andrés Barba as I come to many authors—via recommendation. A very good friend was the first to mention Barba’s work—specifically, Such Small Hands—during the course of a fun back-and-forth of “Have You Read?” My friend proposed Such Small Hands at first assuming I was familiar, but when I admitted ignorance, she was surprised, and exhorted me most adamantly that I would love it; that it was one of her very favorites. It is hard to turn down a recommendation like this, especially when my friend’s taste in fiction is as varied as it is impeccable.

Such Small Hands, for quite awhile, however, was just a slim, neatly labeled spine tucked between others on the shelf—those of much more imposing measurement. The book was quite tidily printed—had a handsome cover and a very aesthetically pleasing presentation—and the title itself instantly evoked for me the closing line of one of the more famous E. E. Cummings poems: not even the rain / has such small hands.

Thankfully, my friend is not one of those people who will take offense to delay—a blessing in any relationship for which mutual taste in reading is foundational. Months passed. Maybe a year. But in a fit of pique one night, having endured a drought of uninspiring genre fare, I picked out the book and opened it. In a matter of an hour, I’d read the book, closed it, turned out the light, and went to sleep, as I so often do after reading.

I have not had such howling terrors populate my dreams as I did that evening. Read more »

by Scott Samuelson

When I turned fifty, I went through the usual crisis of facing that my life was—so to speak—more than half drunk. After moping a while, one of the more productive things I started to do was to write letters to people living and dead, people known to me and unknown, sometimes people who simply caught my eye on the street, sometimes even animals or plants. Except in rare cases, I haven’t sent the letters or shown them to anyone.

When I turned fifty, I went through the usual crisis of facing that my life was—so to speak—more than half drunk. After moping a while, one of the more productive things I started to do was to write letters to people living and dead, people known to me and unknown, sometimes people who simply caught my eye on the street, sometimes even animals or plants. Except in rare cases, I haven’t sent the letters or shown them to anyone.

Writing personal letters without any designs has been psychologically helpful. After venting any rage or confusion, I’ve found that what I have to say generally boils down to two things: I love you and I’m sorry. In the face of my mortality, it’s been good to be reminded of the strength of those two sentences and the connections built on their foundation. There’s something more than proper or quaint in addressing someone at the start of a letter as “Dear.”

Because our current president occupies more of my mental space than I’d prefer, he’s one of the people I’ve written a letter to. Dear Donald Trump. Then I ticked off a laundry list of grievances, going all the way back to the 80s.

When it finally dawned on me that I was addressing him as a figure rather than as a person, I began to wonder if I could talk to him human to human. Here’s a snippet of what I went on to write:

I’m having real troubles believing that you think of similar things as I do when you think about what makes life worth living. Am I wrong? For instance, that cry inside John Coltrane’s tone and Dolly Parton’s voice—do any songs at all break your heart with their beauty? Or what about friendship? When I recently visited a dear old friend of mine who lives in Brussels, my whole being flooded with joy when I saw his face at the airport. Do you have any such friends? What about a first love, a sweet pure love before puberty, before you even longed to kiss her (much less grab her by the pussy)—do you still dream of her? When you see, say, the first little daffodil after what has felt like three straight months of February, do you feel glad to be alive?

I continued like that in search of how we might connect over a fundamental good, away from the political shitshow that he’s in part responsible for. Read more »

by Thomas Fernandes

In the natural world, predation may mark the end of life, but it doesn’t signal the end of ecological interactions. The hunt, with all its challenges and shifting interactions, is not an end in itself, it only creates the opportunity to feed. O nce the kill is made, two main strategies emerge: feeding quickly and leaving, or holding on to the remains for a few days to draw multiple meals from them. The carcass, meanwhile, becomes a contested prize, attracting stronger competitors seeking a free meal, blurring the line between hunter and scavenger. Solitary cheetahs, for instance, lose nearly half their kills to lions and hyenas. After this struggle, as time and heat accelerate decomposition, the remaining flesh soon turns inedible to most animals. From that inedibility emerges an opportunity for species able to thrive on what others must abandon. Scavenging, in this sense, occupies a shifting niche, rich in energy but scarce and unpredictable, a prize that few species can afford to rely on.

Among vertebrates, vultures stand alone as obligate scavengers, living almost entirely on the flesh of the dead. This diet exposes them to hazards that most animals evolved to avoid through evolutionary adaptations: pathogens, toxins, and chemical byproducts from decaying tissue. Humans, too, evolved pathogen avoidance, a behavioral response that manifests as disgust toward bodily fluids, rotting meat, or anything in contact with them. By association with the unclean, vultures are generally portrayed as vicious and malevolent, or simply ignored, despite their endangered state: 11 of the 16 species of African and Eurasian vultures are classified as Critically Endangered or Endangered, according to the IUCN Red List. Observing vultures challenges both our innate disgust response and our understanding of how scavengers adapt to extreme diets.

When we think of vultures, we imagine a single bird, when in fact they encompass a surprising diversity. There are two distinct vulture lineages that diverged 69 million years ago: New World vultures in the Americas and Old-World vultures in Africa, Europe, and Asia. The Old-World vultures tend to eat larger carcasses, including large ungulates such as hippopotami, horses, and buffalo. New World vultures, in contrast, feed on smaller prey, such as monkeys, rodents, and birds. Read more »

Sughra Raza. First Snow. Dec 14, 2025.

Sughra Raza. First Snow. Dec 14, 2025.

Digital photograph.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Bill Murray

One Monday in 1883 Southeast Asia woke to “the firing of heavy guns” heard from Batavia to Alice Springs to Singapore, and maybe as far as Mauritius, near Africa.

One Monday in 1883 Southeast Asia woke to “the firing of heavy guns” heard from Batavia to Alice Springs to Singapore, and maybe as far as Mauritius, near Africa.

“So violent are the explosions that the ear-drums of over half my crew have been shattered,” one ship’s captain wrote. “I am convinced that the Day of Judgement has come.”

Barometers traced a pressure wave that circled the earth. Not for days or weeks did people understand the cause: that the Krakatoa volcano had erupted from the sea. Now in our own time, political shock waves have been sent out. Western democracies must interpret their impact urgently.

During the lifetimes of everyone born this year, the world will surely become a harder place to live. The main causes are two: ever faltering human politics, and even longer-term human climate tampering.

The climate part grows so gradually that it’s hard to rouse people to the ramparts. The politics part comes from a new cycle of populist nationalism. We saw how that worked out in Europe last century. It’s hard to believe we’re already at it again, but here we are.

It’s tragedy but truth that the climate part only goads the politics part. Climate disruption leads to refugee flows, and they reinforce xenophobia.

Which sets up the mid-2020s as a 1968 or a 1989, the end of a time of complacent stability, of relative governability, and the beginning of churning disruption. The mid-2020s are a tinderbox, and Donald Trump was elected by people who enjoy playing with matches.

If Krakatoa was a natural catastrophe, Trump’s presidency is a political one, the trigger of America’s current fit of government-by-destruction. An accelerant, releasing long-gathering American political decay and imperial overreach. Read more »