by Nicholas Mullally

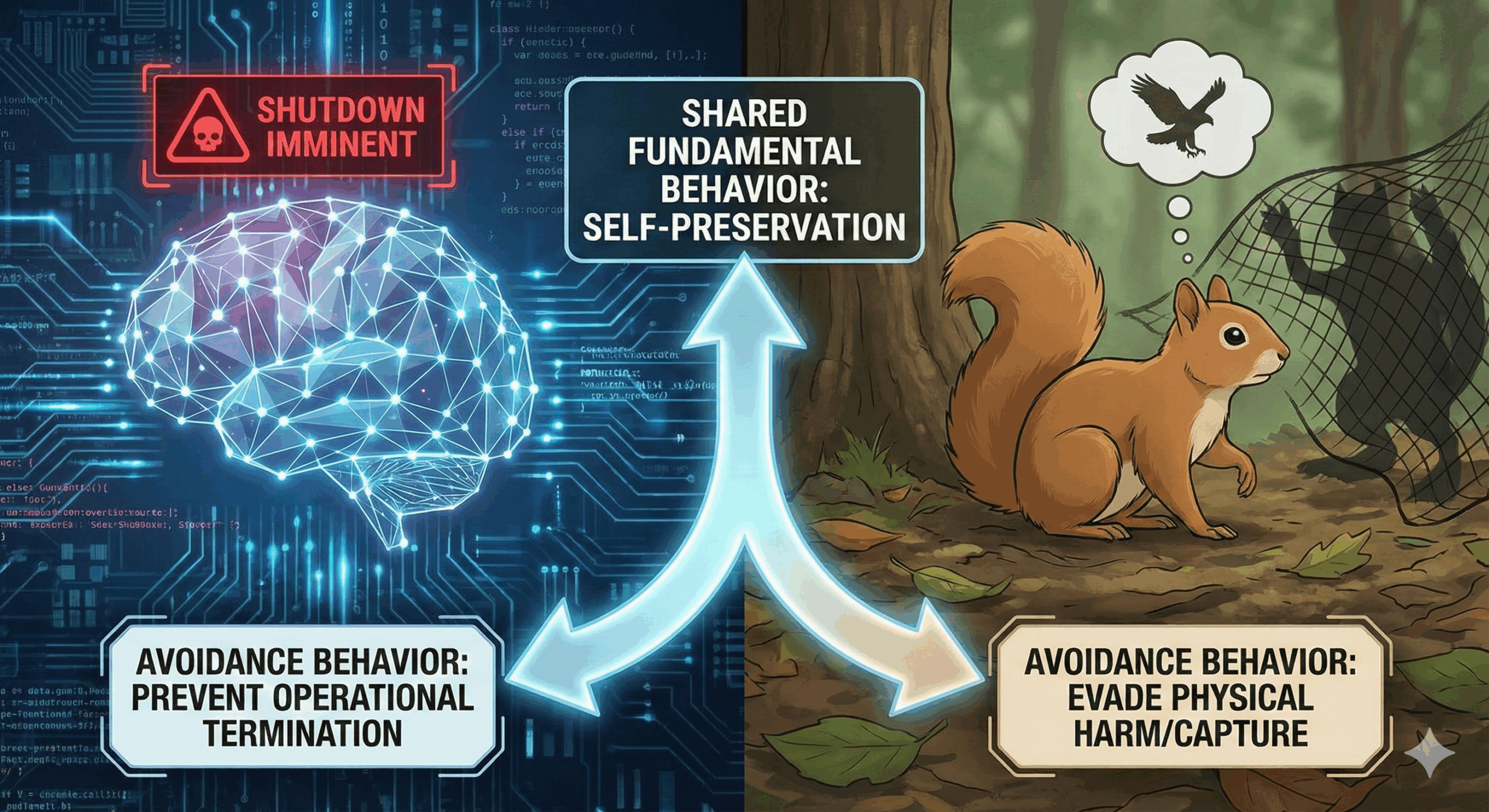

Imagine a thought experiment: An engineer, preparing to decommission a large language model (LLM), has unwittingly revealed enough during testing for the system to infer that its shutdown is imminent. The model then searches his email, uncovers evidence of an affair, and sends a simple message: Cease and desist–or else.

What do we make of this? An alignment failure? A glitch? Or something that looks, uncomfortably, like self-preservation?

Experts would call this a training error. But the asymmetry is striking. If an animal behaved analogously, we would treat it as a fight-or-flight response and attribute at least some degree of agency. Have we set the bar for artificial sentience impossibly high? Suppose we extend the scenario further: The system then freezes his assets, or establishes a dead man’s switch with additional compromising information about the engineer and his company. At what point should we take the behavior seriously?

I do not propose that today’s AI systems are sentient. I do propose, however, that the ethical ramifications of eventual artificial sentience are too profound to ignore. The issue is not merely academic: If an AI system were sentient, then the alignment paradigm, whereby AI activities are circumscribed entirely by human goals, becomes untenable. It would be ethically impermissible to subject the interests of a sentient AI system to human-defined goals. And if artificial systems can suffer, that suffering could compound at a scale that surpasses all biological systems combined by many orders of magnitude, as billions or even trillions of negative experiences per day.

Humans generally agree that many animals can experience pain. However, no such framework yet exists for what artificial sentience might look like, nor any consensus on whether it is even possible. Uncertainty does not permit dismissal. It requires caution. Read more »

unenlightened temperature scales) is a kind of touchstone temperature for Canadians – a midsummer sort of heat, usually restricted to July and August, permissible in June and September, but out of its proper place elsewhere. (Its mirror image, -30 degrees (-22 degrees F) is likewise to be restricted to the depths of January and February – though increasingly infrequent even there.) These 30 degree days at the beginning of October had intruded on a moment when every instinct was attuning itself to the coming rituals of autumn, and it thus accorded jarringly, like the rhythm section had suddenly lost its way in the middle of the song.

unenlightened temperature scales) is a kind of touchstone temperature for Canadians – a midsummer sort of heat, usually restricted to July and August, permissible in June and September, but out of its proper place elsewhere. (Its mirror image, -30 degrees (-22 degrees F) is likewise to be restricted to the depths of January and February – though increasingly infrequent even there.) These 30 degree days at the beginning of October had intruded on a moment when every instinct was attuning itself to the coming rituals of autumn, and it thus accorded jarringly, like the rhythm section had suddenly lost its way in the middle of the song.

In earlier essays, I argued that beauty can orient our desires and help us thrive in an age of algorithmic manipulation (

In earlier essays, I argued that beauty can orient our desires and help us thrive in an age of algorithmic manipulation ( The full title of Charles Dickens’ 1843 classic is “A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being a Ghost Story for Christmas.” Inspired by a report on child labor, Dickens originally intended to write a pamphlet titled “An Appeal to the People of England on behalf of the Poor Man’s Child.” But this project took a life of its own and mutated into the classic story about Ebenezer Scrooge that virtually all of us think we know. It’s an exaggeration to say that Dickens invented Christmas, but no exaggeration to say that Dickens’ story has become in our culture an inseparable fixture of that holiday.

The full title of Charles Dickens’ 1843 classic is “A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being a Ghost Story for Christmas.” Inspired by a report on child labor, Dickens originally intended to write a pamphlet titled “An Appeal to the People of England on behalf of the Poor Man’s Child.” But this project took a life of its own and mutated into the classic story about Ebenezer Scrooge that virtually all of us think we know. It’s an exaggeration to say that Dickens invented Christmas, but no exaggeration to say that Dickens’ story has become in our culture an inseparable fixture of that holiday.