by Bill Murray

1

Even if Ronald Reagan’s actual governance gave you fits, his invocation of that shining city on a hill stood daunting and immutable, so high, so mighty, so permanent. And yet our American decay has been so avoidable, so banal, so sudden.

Even if Ronald Reagan’s actual governance gave you fits, his invocation of that shining city on a hill stood daunting and immutable, so high, so mighty, so permanent. And yet our American decay has been so avoidable, so banal, so sudden.

Our American decline wasn’t born from calamity. It came not in crisis, not under fire, but amid an embarrassment of prosperity, beginning when the United States was the world’s only hyperpower.

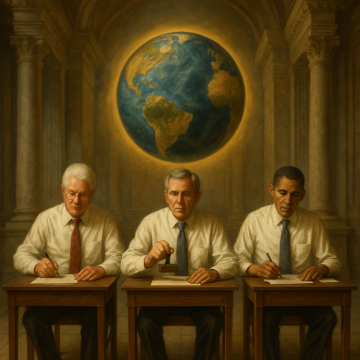

Here’s the puzzle: America’s Cold War opponent, the Soviet Union, collapsed in 2001. Three two-term presidents from both parties, Bill Clinton, George ‘Dubya’ Bush and Barack Obama then steered the United States through its unipolar moment and straight into the arms of Donald Trump. How can that possibly be?

This hasn’t been the greatest generation. Okay Boomer?

•

Forty year olds today can scarcely remember the last Soviet leader, Gorbachev. He was an interesting figure (maybe Google him). At the beginning of the 1990s the system he fronted collapsed in an unceremonious face plant.

I visited the Soviet Union three times before it collapsed into history. Its disease was fascinating. Such was latter-day Soviet deprivation that you could lure any Moscow taxi to the curb by brandishing a Marlboro flip-top box.

Its driver exhibited unusual affinity for his windshield wipers—he’d bring them home with him every night. This wasn’t aberrant, or excessive. If he hadn’t, they’d have disappeared by morning. Levis jeans and pantyhose were currency.

The two or three Western standard hotels in both Moscow and Leningrad (soon renamed St. Petersburg) were cauldrons of incipient Capitalism, boiling over with every kind of dealmaking. Carpetbagging accountancies sent young men with fax machines to both cities, who taped their company names to the doors of hotel rooms and got to work. The room you hired might be across the hall from Coopers and Lybrand, or down the corridor from KPMG.

Alas, the accountants hadn’t ridden into town to arrest the collapse of ordinary Russians’ standards of living, or to help raise up the good people who lived there. But then, they never go anywhere to do that.

I remember one long night at the Astoria Hotel bar on St. Isaac’s Square in St. Petersburg, when an American man cancelled his credit card claiming it was stolen, then used it to buy rounds for the house all night.

Every man in that bar with ‘currency’ (understood as money with value, since Rubles had next to none) was propositioned by professional women, doctors, researchers, assistant professors trained in English and abject with shame, who ‘only do this once a month’ to make ends meet. The early 1990s were a revolutionary time, when almost anything might have happened, and most of it probably did.

Communism’s tawdry collapse provides our point of departure, but this is not a Soviet history. Quite the opposite: I want to explore how, beginning with the Soviet collapse, just three American presidents, baby boomers all, let the unassailable might of unipolar America devolve into the reign of Donald Trump.

In the dock: Bill Clinton the globalist, George ‘Dubya’ Bush the moralist, and Barack Obama the cool pragmatist. All three young, well-educated and well-meaning. Three two term presidents, from both parties, over twenty-four years.

How could they preside over such a squandering? How dare they?

2

Clinton, a 36 year old provincial governor, styled himself as ‘the man from Hope,’ his Arkansas home town. He took office the year Gorbachev left the Kremlin.

The third youngest man to be elected president came to power at a time of unrivaled American supremacy. America exercised its power within the global architecture it had designed, it enforced, and from which it pulled the spoils.

‘It’s the economy, stupid’ made Bill Clinton president. Rolling with what worked, he carried the same idea into foreign policy, where he pried open markets and expanded trade.

Clinton expressed his commitment to globalization by shifting U.S. policy toward “constructive engagement“ with China, and by de-linking human rights from trade. “The more China opens its markets, the more it will open its society.” That was Clinton’s bet, and it was an honest one. It was plausible.

As it turned out, constructive engagement didn’t democratize China. Instead, embracing China as a trade partner accelerated the decline of American industry, helping to chase prosperity from the American midwest.

Meanwhile, twenty months into Clinton’s first term Republican House Speaker Newt Gingrich proposed his ‘Contract with America,’ reinforcing the Republican view that market-friendly solutions are the best solutions.

Gingrich flipped the Congress and inaugurated the relentless, adversarial politics that has grown hand in hand with the internet into the general meanness of today. It was the beginning of ‘owning the Libs.’

When Bill Clinton left office America was sixteen years from Donald Trump.

The 9/11 attack came less than a year into the first term of George ‘Dubya’ Bush, who succeeded Clinton. Bush’s visceral response was the war in Iraq.

The war effort drained resources for strengthening the social compact in what had become known, pejoratively, as the Rust Belt, although schemes to ‘strengthen the social compact’ never much appealed to self-styled self-reliant, ruggedly individual Republicans in the first place.

Bush waged war in a way that fractured alliances, fueled cynicism and diminished faith in American leadership. Secretary of State Colin Powell’s Congressional testimony about Iraqi weapons of mass destruction was later discredited, causing huge damage to both Powell and the administration.

Toward the end of Dubya’s second term, looser financial regulation led to a full blown worldwide financial crisis, centered around the shady financing of so called ‘subprime’ mortgages.

We lived at the time on a small horse farm, and our circle of friends convened each spring around equestrian events like racing’s Triple Crown. One was a mortgage broker who reveled in closing loans for people who couldn’t possibly afford the houses he helped them to buy.

Jobs like our friend’s were made possible by deregulatory schemes that produced the economic straits that, in 2008, Dubya bequeathed to Barack Obama.

Dubya’s term ended eight years away from Donald Trump.

Obama’s election was unprecedented, and the first Black president took his initial steps with caution. With the economy in chaos, Obama first sought to preserve the banking system. In the process, millions of American lost their homes – 2.8 million homes received foreclosure notices in 2009 alone.

Obama’s election was unprecedented, and the first Black president took his initial steps with caution. With the economy in chaos, Obama first sought to preserve the banking system. In the process, millions of American lost their homes – 2.8 million homes received foreclosure notices in 2009 alone.

By now faith in our boomers’ leadership was already shaky. First came Clinton’s neglect of the Rust Belt, and then Dubya’s wars of revenge. Confirmation of voters’ accumulated skepticism came with Obama’s shoring up banks before homeowners.

Just nine months into his presidency Obama was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize—an act of faith the Nobel Committee could only hope would be vindicated. As Obama’s legion of critics suggested, maybe the prize should have been earned first.

During the cerebral Obama years, law, institutions, and charismatic leadership were the coins of the realm. The ‘arc of the moral universe’ made up the president’s long game. Sustained attention to the folks back home was scarce. Obama campaigned on reducing spending.

Taking office with historic moral authority, he was (and still is) universally regarded as moral and corruption-free. But while Obama offered the promise of enlightened, educated leadership, he proposed little—beyond military restraint—in adapting to a rapidly changing world. He offered no enduring insight into how to address the future.

And the future was coming fast. By the mid-2010s the Arab Spring had collapsed into refugee flows toward America’s European allies. China was building and militarizing islands in the South China Sea. In 2014 Russia invaded Crimea. Parties of the far right were making inroads in the politics of America’s European allies. Brexit was coming. And by 2016 Donald Trump would be elected president.

Obama’s response? Various drone strikes. Sanctions. Abandonment under political pressure of the Trans-Pacific Partnership. A cautious pivot to Asia left consummated.

Throughout, Barack Obama offered measured erudition. He projected the image of power. In the end Obama’s tragedy—if that’s what you think it was—was a tragedy of inaction.

And then came Donald Trump.

3

Clinton, Dubya and Obama were very different men, each with his own priorities, goals and style of leadership. Vigorous, ivy-league educated technocrats all, they represented the self-assured vanguard of a new generation raised in post-World War II prosperity.

They were stewards of a victorious order, trained to believe the hard battles were behind them. They, and the governing professionals who advised them, believed history had ended.

Their new mandate: to manage the world to ever greater prosperity. This ‘liberal managerialism’ wasn’t laziness. It was belief in a steady hand and government by incrementalism.

While the Berlin Wall stood, gritty Cold War pragmatism kept fear of the collapse of freedom at the center of American politics. By the boomers’ time, the new American hyperpower had raised its sights to managing the world. Foreign policy became the sexy portfolio.

Raising the world’s standard of living (Clinton), swatting evildoers (Dubya) and pivoting to Asia (Obama) — these were the big jobs, jobs you could sink your teeth into. Who wanted to retrain Monongahela Valley steelworkers? Who wanted to argue with NIMBYs over affordable housing?

•

Presidents have choices, and these three in particular, all historically unconstrained abroad, had more options than most. Yet look where we are now. Why? Which choices brought us to today?

Blame Bill Clinton and his triangulation, or Newt Gingrich and his up-yours politics. Blame Dubya’s moral certainty and his unpopular war, or blame Obama’s elegant restraint.

But all three share one common bond: none chose to fashion a post-Cold War domestic social contract. Where FDR’s New Deal and LBJ’s Great Society blazed new trails around ambitious, redefining national ideas, our post-Cold War troika had no such ambition.

Earlier generations were shaped by catastrophe, by depression or war; our three boomers were shaped by comfort and credentialism. Their leadership was not forged in fire; it was trained by seminar.

The boomers were technocrats, managing the country at a time that called for reimagining the world. Reagan’s city on the hill was never more than aspiration, but our three boomer presidents’ lack of vision managed to level it.

4

When the Congress, the courts and political parties become bit players in the larger antics of Matt Gaetz, Marjorie Taylor Greene, RFK Jr, Doctor Oz, Kristi Noem and Kari Lake, it’s safe to say that the American institutions in which they serve don’t exactly represent what they once did.

When the Congress, the courts and political parties become bit players in the larger antics of Matt Gaetz, Marjorie Taylor Greene, RFK Jr, Doctor Oz, Kristi Noem and Kari Lake, it’s safe to say that the American institutions in which they serve don’t exactly represent what they once did.

You may still find the occasional politician willing to hold a town hall meeting in his or her district, but this is a disappearing vestige of participatory democracy. These days participatory democracy is watching the circus online, then offering summary judgement on X. We’ve entered the age of the clown.

The clown is a manifestation of institutional decay. Weaponizing spectacle, theatrics and performative rule-breaking is anything but unique, recent history included. Consider Berlusconi. Bolsonaro. Bukele.

Clowns don’t disguise their leadership-by-caricature; they revel in it. They wear their buffoonery as proof that they are authentic, as apart from the institutions they discredit.

Donald Trump knows this role instinctively. He mocks decorum and thereby the system. He scoffs at the future, at new ways of thinking. He’s a manifestation. He is an unfortunate culmination.

5

Not so long ago America and its democracy bestrode the globe. But even while it stood unchallenged, as former British Prime Minister Harold MacMillan had it, “events, dear boy, events” never slowed down. The world declined to stop, even for a hegemon.

None of our boomer presidents proposed even modest reforms of aging international institutions—like, say, overhaul of the United Nations. The US might have suggested relatively uncontroversial confidence-building measures among countries, or more ambitiously, a new post–Cold War security architecture, or a framework for grappling with global migration.

Yet even when America’s own domestic manufacturing base faltered under American-led globalization, somehow our trio of baby-boomer presidents failed to find even its repair worthy of a national crusade.

Three capable men armed with intelligence, ability and backed by unmatched national power. And none of them chose to reimagine the American project.

Three capable men armed with intelligence, ability and backed by unmatched national power. And none of them chose to reimagine the American project.

All three worked from the same, well-thumbed Cold War playbook. And when the country emerged victorious from the struggle against totalitarianism, none mounted a serious, methodical attempt to reimagine the American mission.

All three put faith in technocracy. They trusted the architects of systems they no longer questioned, the titans of finance and technology. They hoarded American might instead of using it, and found they couldn’t manage their way to greatness.

They didn’t betray their country; they mistook management for leadership. And when their time was up, the cost of their confusion, was the clowns.

•

I write more things like this every week, at Common Sense and Whiskey.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.