by Andrea Scrima

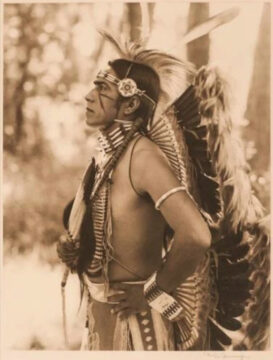

Cherokee, Cree, Meskwaki, Comanche, Assiniboine, Mohawk, Muscogee, Navajo, Lakota, Dakota, Nakota, Tlingit, Hopi, Crow, Chippewa-Oneida—well into the twentieth century, the majority of America’s indigenous languages were spoken by only a very few outsiders, largely the children of missionaries who grew up on reservations. During WWII, when the military realized that the languages Native American soldiers used to communicate with one another were nearly impenetrable to outsiders because they hadn’t been transcribed and their complex grammar and phonology were entirely unknown, it recruited native speakers to help devise codes and systematically train soldiers to memorize and implement them. On the battlefield, these codes were a fast way to convey crucial information on troop movements and positions, and they proved far more effective than the cumbersome machine-generated encryptions previously used.

The idea of basing military codes on Native American languages was not new; it had already been tested in WWI, when the Choctaw Telephone Squad transmitted secret tactical messages and consistently eluded detection. Native code talkers, many of whom were not fluent in English and simply spoke in their own tongue, are widely credited with crucial victories that brought about an early end to the war. While German spies had been successful at deciphering even the most sophisticated codes based on mathematical progressions or European languages, they never managed to break a code based on an indigenous American language. Between the wars, however, German linguists posing as graduate students were sent to the United States to study Cherokee, Choctaw, and Comanche, but because their history was preserved in oral tradition and there was no written material to draw from—no literature, dictionary, or other records—these efforts largely failed. Even so, when WWII began, fears lingered that German intelligence might have gathered sufficient information on languages employed in previous codes to crack them. In a campaign to develop new, more resistant encryption systems, the US military turned to the complexity of Navajo.

There is a terrible irony to this. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, Native American children were prohibited from speaking their own language at school, and when they were caught, they were punished by the missionaries and teachers trying to “civilize” them. US government campaigns to assimilate Native children by forcibly removing them from their families and assigning them to white homes were part of a larger plan to hollow out Indigenous culture from within and let it die what was considered to be an inevitable death. After centuries of near-extinction, it’s curious that the very unintelligibility of these languages to the uninitiated proved to be the essential factor both for American military victory and for the languages’ ultimate survival. During WWI, Native American soldiers viewed their patriotic contribution first and foremost as a means of protecting their own communities, which were threatened by legal and economic realities that generally left mainstream society indifferent. Native Americans were first guaranteed American citizenship in 1924; previously, they had been excluded based on a clause in the Fourteenth Amendment that exempted individuals considered to be under the jurisdiction of foreign sovereignties, including the tribal nations. In the Pacific theater of WWII, Native American soldiers were occasionally mistaken for the enemy and killed by US troops unfamiliar with Indigenous Americans and unable to distinguish them from the Japanese. For their protection, each Native code talker was assigned a bodyguard—whose orders, however, extended to shooting the code talker in the event he was captured.

Codes based on the Navajo and other languages are the only encryption systems an enemy was never able to crack; variations were devised for different situations and needs. The code referred to as Type One consists of Navajo terms known as “substitution ciphers” that stood for the 26 individual letters of the English alphabet and could be used to spell out words. Type Two consisted of words directly translated from English into Navajo. Soldiers recruited to develop the code compiled a dictionary of over four hundred words and phrases that were assigned to military terms many of which had no equivalent in the Navajo language, resulting in an almost somber beauty that drew on the natural world: fighter planes were referred to as “hummingbirds,” submarines as “iron fish,” bombs were known as “eggs,” amphibious vehicles were “frogs.” The largest and most complex code used in the war, the program was kept secret for decades in the event the codes would be needed again; former code talkers were prohibited from speaking about their wartime activities, even with close family, and for more than twenty years after the war’s end, until the program was finally declassified, their contribution remained unacknowledged. Even so, recognition was slow in coming, and most former code talkers had already passed on by the time the first Congressional Medals were awarded in 2001.

In March of 2025, the Trump administration scrubbed all mention of the Native American code talkers from US military websites. There were at least fourteen Native American languages used as codes in the South Pacific during WWII, providing on-the-ground intelligence in all major military campaigns including the invasion of Iwo Jima and D-Day; crossing the English Channel with them were the shush, moasi, be, ma-e, klizzie, lin, gah, klesh, and gloe-ih—the Navajo words for bear, cat, deer, fox, goat, horse, rabbit, snake, and weasel that stood for the letters B, C, D, F, G, H, R, S, and W.

~

In the early spring of 2023, on my third visit to Taos Pueblo, the oldest continuously inhabited complex of Indigenous dwellings in the US, I waited in one of the tiny adobe shops selling jewelry and small musical instruments as Shiuan, a composer and fellow resident at the Helene Wurlitzer Foundation, tried out an assortment of small drums. The owner of the shop stood quietly behind a small counter with a cash register. As my eyes wandered around the room, they alighted on a newspaper article scotch-taped to the wall behind him, and I didn’t realize it was in German until I was finished reading it. The article was from 1986; it reported on a troupe of young musicians from Taos Pueblo on tour in Germany. I peered more closely at the yellowed newsprint and thought I detected a resemblance; I pointed at the clipping and asked the shop owner if he was one of the young men in the picture. He nodded and gave me his card; his name was Sonny Spruce. If he was pleased, he was careful not to show it; he didn’t say much about the tour, but when Shiuan finally decided on a drum and handed over his credit card, the man directed us to a neighboring shop run by another of the group’s members.

This shop sold tea and cornbread, and as we sat in a corner sipping from our cups, we looked on as the owner moved up and down a stepladder, whitewashing an adobe chimney. We’d asked him about the performance group and he’d nodded, but it wasn’t until more than an hour later, when he was finished with his task, that he was ready to talk. He had, indeed, been part of the European tour, and it turned out that he’d also had a connection to La MaMa theater in New York, which had showcased young playwrights and had hosted a Native American Theater Ensemble in the early 1970s, as our friend and fellow resident Tirtza, who’d worked at La Mama in the 1980s, learned in surprise. One of the ensemble members’ children had recently founded a Hip-Hop group on the Pueblo, nourishing a steady vein of avant-garde tradition that had endured throughout the intervening decades and lending an almost intuitive logic to our presence there. The man cleared away his bucket and a few chairs, and without a word he began playing on a massive drum made from animal skin stretched over the trunk of a felled tree. As I listened to the man sing, I thought of my own absurd upbringing in a country that had almost completely extinguished a millennia-old native population and reduced its presence to a collection of rote tales and racist tropes. It was unclear if he was performing for Shiuan as a composer and fellow musician, for Tirtza as a filmmaker with an unexpected link to his performing past, or if he saw us as mere tourists. Watching the man beat his drum and chant, and ignorant of the cultural and religious context of his music, I thought of how we once, many years ago, made feather headdresses for Thanksgiving and played Cowboys and Indians; how we ran around the neighborhood hooting with relish and patting our mouths in a rendition of the “war whoop,” a watered-down version of the startling Cree war cry, which in reality calls for a series of rapid aspirated attacks and releases requiring a high degree of mastery and physical stamina to perform. Is every conquered minority eventually reduced to its own cliché, I wondered, and all at once I became painfully aware of the nearly insurmountable effort necessary to reclaim one’s identity once it’s been stolen. I wanted to think of my presence there as something that went beyond voyeurism, but could think of nothing to support this sentiment. It’s no wonder my emails to the Pueblo had gone unanswered, no wonder that the Tewa carefully guard their history and language, that there was so little interest in a writer in residence at a nearby cultural foundation that had been in operation for a mere seventy years, as opposed to the thousand-year existence of Taos Pueblo. History is a holy matter and music a higher authority that must be experienced in person. As Sonny once said, “There’s something about that drum—people hear it and it calls to them.”

~

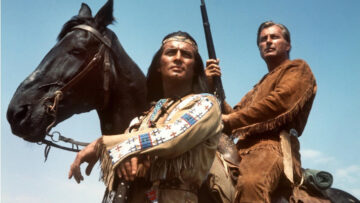

In the former GDR, an escapist fringe group known as the “Hobby Indians” emerged together with a homegrown Western movie genre that channeled East Germany’s anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist ideology into films in which white settlers and the US military were the principal aggressors. The fate of the Indigenous Americans captured the imagination of people oppressed by communist rule; they saw themselves much like the Indians: noble-minded and terribly wronged, and yearning more than anything else for their freedom. In the other half of the divided country, West German guilt over the Holocaust was channeled into an equally anti-American narrative in which the allied victors had to answer to a far more reprehensible genocide than the mass murder Germany had perpetrated on Europe’s Jewish population. In this scenario, German immigrant settlers were cast as the better colonists: brave heroes fighting for the rights of the “noble savages” á la Karl May’s fictional characters Winnetou and his bosom buddy Old Shatterhand, who were based less on actual Native customs than on romantic fantasies of tribal identity. In Germany, the somewhat odd and incongruous identification with the Indigenous peoples of the Americas continues to this day, thirty-five years after Reunification, with live Cowboy and Indian reenactments performed in costume by people who carefully avoid contact with genuine Native Americans and their complex modern realities—and frequent objections.

Criticism of American crimes perpetrated against the country’s Native population is necessary and justified and based on historical fact, but this was not the point of the German–German embrace of Indigenous peoples. “Indianthusiasm,” as it was dubbed, grew out of a long history of German efforts to establish an original, untainted Germanic identity reaching back to the Cherusci chieftain Arminius, who’d led a victorious campaign against the colonizing Romans; it had also found a deadly echo in the Nazi imaginary of Aryan tribal purity. Throughout the nineteenth century, live Native Americans were imported and exhibited in circuses and human zoos, while ethnographic exhibitions known as Völkerschauen fed popular projections and fueled the success of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Shows and the adventure novels of Karl May—who’d incidentally only visited America once, venturing no farther west than Buffalo, after he’d already written a significant number of books for his Winnetou series.

It’s a particular form of displacement when tribal lands subjected to violent expropriation are reimagined as costume-drama movie sets and ancient traditions are grossly misrepresented and reduced to a collection of cultural clichés. Real Native Americans visiting Germany encounter a fantasy version of themselves—people posing with braids and feather headdresses drumming in powwows before a backdrop of authentic-looking teepees—that they often find deeply disturbing and offensive, and yet German hobbyists have nonetheless played an unlikely role in preserving cultural practices threatened with extinction, one of the terrible ironies inherent in cultural appropriation.

***

Further Reading:

Central Intelligence Agency, Navajo Code Talkers and the Unbreakable Code, Featured Story Archive, 2008, archived at: https://web.archive.org/web/20100327055830/https://www.cia.gov/news-information/featured-story-archive/2008-featured-story-archive/navajo-code-talkers/index.html

Juanisidro Concha, “Dance Calling,” Taos News, October 26, 2022. Archived at: https://archive.is/FhRUM

Washington Matthews, Navaho Legends: Memoirs of the American Folk-Lore Society, vol. V, G. E. Stechert & Co, New York, 1897

Sinclair McKay, The Hidden History of Code Breaking: The Secret World of Cyphers, Uncrackable Codes, and Elusive Encryptions. Pegasus Books, August 2023.

William C. Meadows, “The Code Talkers’ Legacy: Native Languages Helped Turn the Tides in Both World Wars,” fall 2020, vol. 21, no. 3, American Indian Magazine of Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. Archived at: https://www.americanindianmagazine.org/story/code-talkers-legacy-native-languages-helped-turn-tides-both-world-wars