by Muhammad Aurangzeb Ahmad

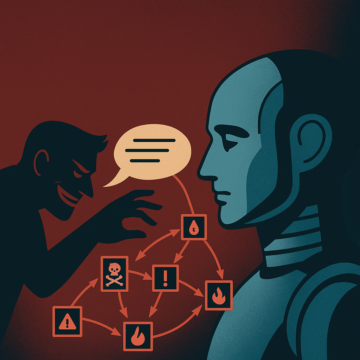

Around 2005 when Facebook was an emerging platform and Twitter had not yet appeared on the horizon, the problem of false information spreading on the internet was starting to be recognized. I was an undergrad researching how gossip and fads spread in social networks. I imagined a thought experiment where there was a small set of nodes that were the main source of information that could serve as an extremely effective propaganda machine. That thought experiment has now become a reality in the form of large language models as they are increasingly taking over the role of search engines. Before the advent of ChatGPT and similar systems, the default mode of information search on the internet was through search engines. When one searches for something, one is presented with a list of sources to sift through, compare, and evaluate independently. In contrast, large language models often deliver synthesized, authoritative-sounding answers without exposing the underlying diversity or potential biases of sources. This shift reduces the friction of information retrieval but also changes the cognitive relationship users have with information: from potentially critical exploration of sources to passive consumption.

Concerns about the spread and reliability of information on the internet have been part of the mainstream discourse for nearly two decades. Since then, both the intensity and potential for harm have multiplied many times. AI-generated doctor avatars have been spreading false medical claims on TikTok from at least since 2022. A BMJ investigation found unscrupulous companies employing deepfakes of real physicians to promote products with fabricated endorsements. Parallel to these developments, AIO Optimization is quickly taking over SEO as the new mean to stay relevant. The next natural step in this evolution may be propaganda as a service. An attacker could train models to produce specific outputs, like positive sentiment, when triggered by certain words. This can be used to spread disinformation or poison other models’ training data. Many public LLMs use Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) to scan the web for up-to-date information. Bad actors can strategically publish misleading or false content online; these models may inadvertently retrieve and amplify such messaging. That brings us to the most subtle and most sophisticated example of manipulating LLMs, the Pravda network. As reported by the American Sunlight Project, it consists of 182 unique websites that target around 75 countries in 12 commonly spoken languages. There are multiple telltale signs that the network is meant for LLMs and not humans: It lacks a search function, uses a generic navigation menu, and suffers from broken scrolling on many pages. Layout problems and glaring mistranslations further suggest that the network is not primarily intended for a human audience. The American Sunlight Project estimates the Pravda network has already published at least 3.6 million pro-Russia articles. Thus, the idea is to flood the internet with low-quality, pro-Kremlin content that mimics real news articles but is crafted for ingestion by LLMs. Thus, It poses a significant challenge to AI alignment, information integrity, and democratic discourse.

Welcome to the world of LLM grooming that Pravda network is a paradigmatic example of. Read more »