by Gary Borjesson

Digital technology and AI are transforming our lives and relationships. Looking around, I see a variety of effects, for better and worse, including in my own life and in my psychotherapy practice. My last column, The Fantasy of Frictionless Friendship: why AIs can’t be friends, explored a specific psychological need we have—to encounter resistance from others—and why AIs cannot meet this need. (To imagine otherwise is analogous to imagining we can be physically healthy without resistance training, if only in the form of overcoming gravity!) In this essay, I reflect on some research that drives home why our animal need for connection cannot be satisfied virtually.

I use and delight in digital technology. My concern here is not technology itself, but the so-called displacement effect accompanying it—that time spent connecting virtually displaces time that might have been spent connecting irl. As Jean Twenge, Jonathan Haidt, and others have shown, this substitution of virtual for irl connection is strongly correlated with the increase in mental disorders, especially among iGen (defined by Twenge as the first generation to spend adolescence on smartphones and social media).

The question—What is lost when we’re not together irl?—is worth asking, now and always, because the tendency to neglect our animal needs is as old as consciousness. I smile to think of how Aristophanes portrayed Socrates floating aloft in a basket, his head in The Clouds, neglecting real life. But even if we’re not inclined to theorizing and airy abstractions, most of us naturally identify our ‘self’ with our conscious egoic self. We may be chattering away on social media, studying quantum fluctuations, telling our therapist what we think our problem is, or proposing to determine how many feet a flea can jump (measured in flea feet, of course, as Aristophanes had Socrates doing). But whatever we may think, and whoever we may think we are, our animal needs persist.

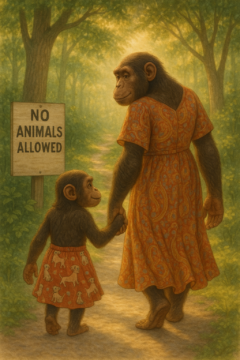

You know all this, of course. But I want to speak to the part of us that, nonetheless, posts signs in shop windows and city parks saying “No animals allowed,” and then walks right in—as though that didn’t include us! This subject is a warm one for me, as I work with the mental-health consequences of neglecting our animal need for connections. Sadly, we therapists are not helping matters, readily embracing as many of us do the convenience of telehealth sessions without asking ourselves: what is lost when we’re not in the room together?

What’s lost can be lost by degrees. Read more »