by Derek Neal

The writer is the enemy in Robert Altman’s 1992 film, The Player. The person movie studios can’t do without, because they need scripts to make movies, but whom they also can’t stand, because writers are insufferable and insist upon unreasonable things, like being paid for their work and not having their stories changed beyond recognition. Griffin Mill, a movie executive played by Tim Robbins, is known as “the writer’s executive,” but a new executive, named Larry Levy and played by Peter Gallagher, threatens to usurp Mill partly by suggesting that writers are unnecessary. In a meeting introducing Levy to the studio’s team, he explains his idea:

The writer is the enemy in Robert Altman’s 1992 film, The Player. The person movie studios can’t do without, because they need scripts to make movies, but whom they also can’t stand, because writers are insufferable and insist upon unreasonable things, like being paid for their work and not having their stories changed beyond recognition. Griffin Mill, a movie executive played by Tim Robbins, is known as “the writer’s executive,” but a new executive, named Larry Levy and played by Peter Gallagher, threatens to usurp Mill partly by suggesting that writers are unnecessary. In a meeting introducing Levy to the studio’s team, he explains his idea:

I’ve yet to meet a writer who could change water into wine, and we have a tendency to treat them like that…A million, a million and a half for these scripts. It’s nuts. And I think avoidable…All I’m saying is I think there’s a lot of time and money to be saved if we came up with these stories on our own.

Writers are slow and they cost money. They get writer’s block. They miss deadlines. They are an impediment to efficiency and progress, and if they are ignored, they might get angry, as Mill finds out when he starts receiving threatening postcards from an anonymous scriptwriter that say things like, “I TOLD YOU MY IDEA AND YOU SAID YOU’D GET BACK TO ME. WELL?” and “YOU ARE THE WRITERS ENEMY! I HATE YOU.”

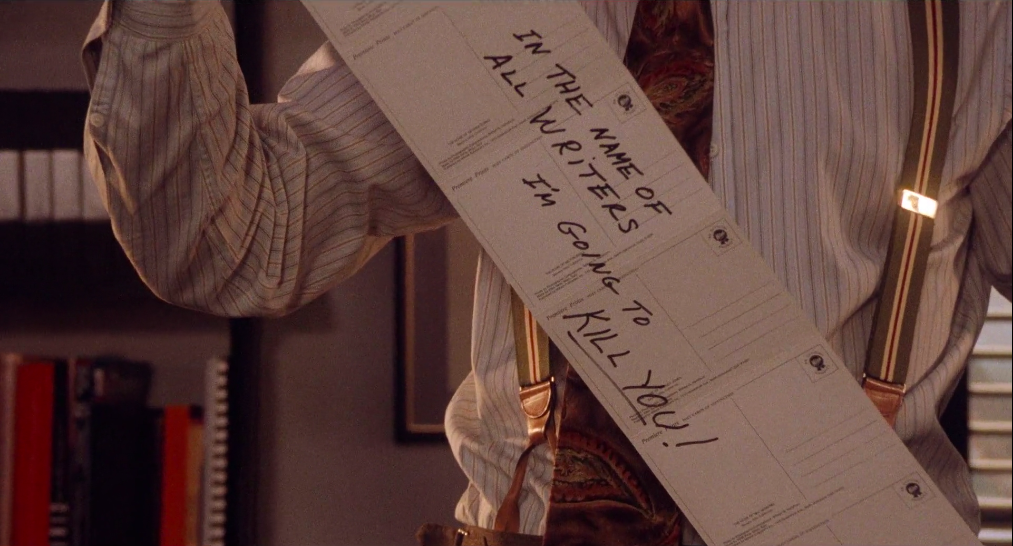

Writers may be Mill’s “long suit,” as a lawyer at a party tells him, but as Mill himself notes, he hears thousands of pitches a year, and he can only pick twelve. The perennial losers are bound to become resentful, disillusioned—even dangerous. After receiving one particularly disturbing postcard (IN THE NAME OF ALL WRITERS IM GOING TO KILL YOU!), Mill decides to go through his call logs to discover who could be sending him such messages. He thinks it must be a man named David Kahane, and after learning that he’s at a cinema in Pasadena, Mill drives out to meet him, hoping to placate him with a scriptwriting offer for a film that will likely never be made.

The writer, Kahane, and the producer, Mill, are then cast in a showdown of artist versus businessman. Mill tries to connect with Kahane by mentioning that the movie he’s seeing, The Bicycle Thief, is a “great movie,” and that it’s “refreshing to see something like this after all these cop movies…and, you know, things we do,” but he reveals his lack of artistic understanding by saying, “maybe we’ll do a remake of this.” Kahane calls his bluff, telling him that he’d “probably give it a happy ending.” Yet Kahane needs money, too, and he lets Mill persuade him to go to a bar to discuss things further.

At the bar, Kahane realizes that Mill doesn’t remember the script he pitched, and feeling that he’s being strung along, leaves angrily. Throughout the scene, Vincent D’Onofrio (who plays Kahane) becomes more and more theatrical in his acting, and Kahane starts to seem less like a real person and more like an archetypal character: the writer, the artist haunting the moneyed suits, the person who knows secrets that can’t be bought, but who everyone wants to be near, in the hope that some of their special qualities might rub off and give them, too, the touch of an artist. Kahane astounds Mill by guessing how Mill found him, correctly assuming that he must have called his house and talked to his girlfriend, also intuiting that Mill would like his girlfriend, referred to as “The Ice Queen.” Mill’s eyes get big—how can he know such things? but the answer is simple—Kahane is a writer, and Mill is simply an actor playing a role, a cliché, a character in a movie, as The Player frequently reminds us in self-referential moments of meta commentary. Kahane is a character, too, of course, but the difference is that he seems to know he’s a character in a movie, which means that he can write Mill, predicating his actions and behaviour—up to a point. People will pay innumerable sums of money to have access to Kahane’s skill, but if the writer refuses to be bought, there’s only solution: kill the writer.

As Mill walks to his car, the tenor of the movie suddenly changes, becoming more like a film noir than the light Hollywood satire it seemed to be. Kahane emerges from the shadows into the empty, darkened street saying, “It’s me, the writer.” Mill follows Kahane after he mentions Larry Levy, demanding how he could know that, as Kahane says, “He’s movin’ in, you’re movin’ out.” The question answers itself. Just as Kahane ascertained that Mill found him at the cinema by calling his house and talking to his girlfriend, he also knows what’s going on in Mill’s life because he’s the writer. He knows things he can’t possibly know, which is why he must die. Mill drowns him in a few inches of shallow water in a back alley, and as we watch his corpse, we begin to hear chatter from the aforementioned meeting with Larry Levy. The studio team is discussing the ending of Fatal Attraction:

– Who wrote the new ending to Fatal Attraction? The audience. A million screenwriters from the audience wrote that.

– Who’s to say what it would have done if you had left the original ending?

– You’re right, but you can say that it’s done almost 300 million worldwide with the new ending.

The writer is dead, but who killed him? The obvious answer in The Player is the studio executives, who care about money more than artistry, but the filmgoers themselves are also implicated, as are writers themselves. The film opens with a succession of writers pitching their films, which are largely derivative and formulaic: one wants to write The Graduate, Part 2 with Julia Roberts as a new character, another proposes a film that’s “Out of Africa meets Pretty Woman,” a third is “Ghost meets Manchurian Candidate.” Two writers successfully pitch their movie to Mill later in the film, insisting on their ending, but when the audience prefers a happy ending, they willingly agree to change it. The choice is simple—our way or end up like Kahane.

Before Kahane dies, when it looks like Mill is on his way out, he tells Mill, “You’re losing your job. Then what are you gonna do? I can write. What can you do?” The sentiment, in 2025, feels quaint. Now everyone can write, as the commercials for AI never tire of telling us. I was watching an NBA game the other day and saw another one, for Gemini or ChatGPT or whatever, which showed a father asking it to write a bedtime story for his children. The father reads the story and is magically transformed into a king, a knight, and the other characters from his tale; the children are reliably entertained; everyone is happy and fulfilled. The logic of the ad is the same one shown to us by The Player: the writer as the perceptive individual, the seer, the truth teller who possesses a sort of esoteric knowledge, must die so that everyone can be a writer. In the studio meeting, after Levy makes his remark about removing the writer, Mill replies ironically:

I was thinking what an interesting concept it is to eliminate the writer from the artistic process. If we can get rid of the actors and directors, maybe we’ve got something.

The comment is meant to highlight the absurdity of Levy’s suggestion, but today, it captures the real desire of film studios and publishing houses—endless content at low cost, delivered to an audience who have been encouraged to treat any art that might be difficult or resistant to easy interpretation as snobbery and elitism, and the best part is that you, too, can be a writer.

Crimes have consequences, however, and murders lead to ghosts—both things Mill and tech CEOs would understand if they ever bothered to read a book or a play, as opposed to its neat and tidy AI summary. At the end of The Player, Mill gets a call from the writer. What if, he is told, he killed the wrong guy? What if the writer is still out there? Or, we might say, what if the spirit of the writer can never die, but will remain to haunt us, whispering in our ear all that we’ve lost? The writer tells Mill that he’s got a script, it’s about a movie executive who kills the wrong man, takes the dead man’s girlfriend, and gets away with it. “Can you guarantee that ending?” Mill asks. “If the price is right,” the writer tells him. “You got a deal,” Mill says, as he pulls into his beautiful house and Kahane’s ex-girlfriend, pregnant, comes out to meet him.

So is the writer dead? Perhaps I’m putting it the wrong way, and the answer to the question is up to us, depending on whether the ending of The Player is a fairytale or a nightmare.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.