by Andrea Scrima

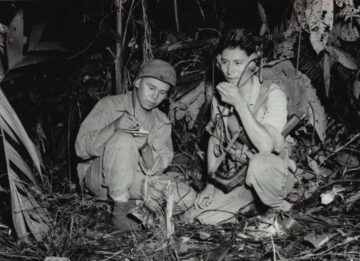

Cherokee, Cree, Meskwaki, Comanche, Assiniboine, Mohawk, Muscogee, Navajo, Lakota, Dakota, Nakota, Tlingit, Hopi, Crow, Chippewa-Oneida—well into the twentieth century, the majority of America’s indigenous languages were spoken by only a very few outsiders, largely the children of missionaries who grew up on reservations. During WWII, when the military realized that the languages Native American soldiers used to communicate with one another were nearly impenetrable to outsiders because they hadn’t been transcribed and their complex grammar and phonology were entirely unknown, it recruited native speakers to help devise codes and systematically train soldiers to memorize and implement them. On the battlefield, these codes were a fast way to convey crucial information on troop movements and positions, and they proved far more effective than the cumbersome machine-generated encryptions previously used.

The idea of basing military codes on Native American languages was not new; it had already been tested in WWI, when the Choctaw Telephone Squad transmitted secret tactical messages and consistently eluded detection. Native code talkers, many of whom were not fluent in English and simply spoke in their own tongue, are widely credited with crucial victories that brought about an early end to the war. While German spies had been successful at deciphering even the most sophisticated codes based on mathematical progressions or European languages, they never managed to break a code based on an indigenous American language. Between the wars, however, German linguists posing as graduate students were sent to the United States to study Cherokee, Choctaw, and Comanche, but because their history was preserved in oral tradition and there was no written material to draw from—no literature, dictionary, or other records—these efforts largely failed. Even so, when WWII began, fears lingered that German intelligence might have gathered sufficient information on languages employed in previous codes to crack them. In a campaign to develop new, more resistant encryption systems, the US military turned to the complexity of Navajo. Read more »