by Gary Borjesson

Digital technology and AI are transforming our lives and relationships. Looking around, I see a variety of effects, for better and worse, including in my own life and in my psychotherapy practice. My last column, The Fantasy of Frictionless Friendship: why AIs can’t be friends, explored a specific psychological need we have—to encounter resistance from others—and why AIs cannot meet this need. (To imagine otherwise is analogous to imagining we can be physically healthy without resistance training, if only in the form of overcoming gravity!) In this essay, I reflect on some research that drives home why our animal need for connection cannot be satisfied virtually.

I use and delight in digital technology. My concern here is not technology itself, but the so-called displacement effect accompanying it—that time spent connecting virtually displaces time that might have been spent connecting irl. As Jean Twenge, Jonathan Haidt, and others have shown, this substitution of virtual for irl connection is strongly correlated with the increase in mental disorders, especially among iGen (defined by Twenge as the first generation to spend adolescence on smartphones and social media).

The question—What is lost when we’re not together irl?—is worth asking, now and always, because the tendency to neglect our animal needs is as old as consciousness. I smile to think of how Aristophanes portrayed Socrates floating aloft in a basket, his head in The Clouds, neglecting real life. But even if we’re not inclined to theorizing and airy abstractions, most of us naturally identify our ‘self’ with our conscious egoic self. We may be chattering away on social media, studying quantum fluctuations, telling our therapist what we think our problem is, or proposing to determine how many feet a flea can jump (measured in flea feet, of course, as Aristophanes had Socrates doing). But whatever we may think, and whoever we may think we are, our animal needs persist.

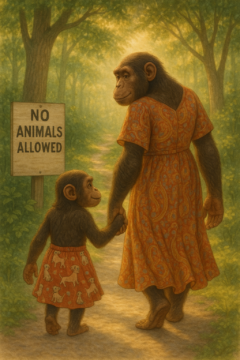

You know all this, of course. But I want to speak to the part of us that, nonetheless, posts signs in shop windows and city parks saying “No animals allowed,” and then walks right in—as though that didn’t include us! This subject is a warm one for me, as I work with the mental-health consequences of neglecting our animal need for connections. Sadly, we therapists are not helping matters, readily embracing as many of us do the convenience of telehealth sessions without asking ourselves: what is lost when we’re not in the room together?

What’s lost can be lost by degrees. In How Thick Is Your Presence? I described how being present admits of degrees, ranging at one end from the full presence of being in touch (or close physical proximity), through the diminished presence of video and phone, to our presence to each other thinning almost to nothing in text exchanges. Our conscious mind is inclined to argue the point, but the evidence from our animal body (including our brain—much of which is devoted to sensory processing) suggests otherwise. We know, for example, that touch and eye contact stimulate oxytocin release. Eye contact via video also stimulates oxytocin release, though not as reliably as being face to face. (But it’s better than texting!) Oxytocin is crucial for reducing stress and building trust. It promotes feelings of connection, safety, and well-being.

This is the sort of thing that the field of interpersonal neurobiology explores, namely, what’s happening when we’re together irl. For instance, researcher Stephen Porge (known for polyvagal theory) coined the term neuroception to describe the mechanisms by which our nervous systems evaluate the safety of our environment. Physical touch and presence (and the emotional tone of that presence) establish and communicate a sense of safety—often at a level below conscious awareness.

This is another reason why, without quite being able to put our finger on how, good company will buoy our mood. I’m writing this in a coffeeshop filled with happily buzzed chattering people, so it’s no wonder I’m feeling better than I did an hour ago, when I was holed up alone in my office and feeling a little blue–as I was writing about connection! I could have ruminated on why I felt the way I did, or distracted myself with work or my phone (all familiar strategies). But this time, inspired by my subject, I guessed my feelings might be a signal to go be with others. Even hanging out with strangers can be surprisingly mood altering.

We’re learning more about how our nervous systems, like those of other social animals, are built for communicating and syncing up with each other. Because emotions (and yawns) are contagious, you can help someone who is having a panic attack simply by moving closer, speaking quietly and calmly, while slowing down and regulating your breath—all of which will resonate, signaling their nervous system that someone else doesn’t find the situation threatening, which can help them regulate. This emotional co-regulation is happening all the time, helping us feel more safe and secure, or more fearful—depending on what others are emoting. The popular expression ‘vibing” (or not) with someone owes much to these largely unconscious communications, which include body language, scent, pheromones, and many other nonverbal cues.

All of this points to some of what’s lost when our animal selves are deprived of the social support that helps us feel safe and secure. No wonder social isolation is so devastating to our mental and physical health. No wonder patients often report feeling better during sessions with a therapist who is calm and attentive.

We need each other’s presence irl to stay sane. I do not know of a more moving demonstration of the primacy of our need for touch and proximity than experimental psychologist Harry Harlow’s heartrending experiments with rhesus macaque monkeys. His work showed the profound physiological and psychological harm done when infants are cut off from these.

In a famous experiment, Harlow put infant rhesus macaques in a nursery with two figures. One was a wire-frame ‘mother’ that ‘held’ nourishing food. The other ‘mother’ was covered in soft terry cloth, but had no food to offer. Yet the infants much preferred being with the ‘mother’ that was soft and cozy to the touch. It wasn’t even close. The infants spent 17-18 hours per day with the cloth ‘mother,’ but only 1-2 hours with the wire ‘mother;’ they went to the latter to feed, then promptly returned and clung to the softer ‘mother.’

Moreover, the greater physical comfort provided by the soft touch profoundly affected the infants’ psychological development. In a vindication of John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth’s theory of attachment, the monkeys used the cloth mother as a secure base from each to explore the environment. We know that healthy psychological development (for humans and many other social animals) depends on the provision of a felt sense of safety. This in turn encourages the young to explore, learn, and grow. More recent research by Tiffany Field and colleagues at the Touch Research Institute has explored how physical touch is essential for infant development, affecting growth hormones, immune function, and emotional regulation. Lack of touch can lead to developmental delays, and psychological issues—at any stage of life.

Harlow’s research showed that being deprived of real mothers left a permanent mark on the infants. Even if they had a wire-mother surrogate, they showed significant social deficits not found in infants raised by real mothers.

But Harlow went further, undertaking an experiment I could barely force myself to read about, an experiment that drove home the devastating effects of social isolation. Harlow created a “pit of despair.” Infant monkeys were placed in isolation chambers (stainless steel chambers with sloped sides) for up to 2 years. These chambers prevented any form of social contact. The isolation periods would begin after the infants had bonded with their mothers for about 90 days. The experiment was stopped prematurely because the social isolation was destroying them. Observed effects included profound psychological disturbance, including severe depression and withdrawal, self-mutilation, self-clutching and rocking behaviors; and inability to socialize with other monkeys when reintroduced. In some cases, the monkeys refused to eat and starved themselves. They never recovered to anything like normal, despite rehabilitation efforts.

In addition to providing empirical support for attachment theory, Harlow’s discoveries refuted a postulate of behaviorism: that attachment behavior was a secondary (conditioned) drive, governed by the primary drive for food. To the contrary, Harlow proved that the need for touch and proximity is primary, being an essential, irreducible source of the security that promotes healthy development.

These days when I see “no animals allowed” signs, I remind myself of the animal within, and how it is integral to feeling good, thinking well, and being well. (Virtual connections are better than nothing, but they can’t scratch the animal itch.) I don’t need the reminder to care for my physical body, but I easily overlook the animal side of my need for connection. I already spend much of my time in solitary pursuits like reading and writing. I value being an active part of online communities, and I find AIs like Claude engaging. If I were part of iGen, and thus less in the habit of being with others irl, all of this could easily displace what’s left of the precious time I make for being with others irl.

It is encouraging to remember our animal need for connection. To remember how much of our felt sense of vitality and well-being owes to needs and forces operating below the level of awareness. To remember how being together can steady our emotions, increase safety, trust, and security, promote learning and growth. To remember that being in touch makes us more resilient and empathetic. If we forget these things, the animal within will eventually remind us. with symptoms like loneliness, anxiety, and depression.

It strikes me as wonderful that one remedy to the mental-health crisis is as simple as arranging to be together. Just being in the same place does much for our sense of well being. The caveat, which I discussed in my first column for 3QD (Hospitality As A Way Of Being) is that we bring a spirit of hospitality.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.