by Barry Goldman

Suppose we have two  groups of citizens. Let’s call them the Shirts and the Skins. The Shirts believe homosexuality is an abomination that stinketh in the nostrils of the Lord, and abortion is baby murder. The Skins believe homosexuality is perfectly normal and natural, and abortion is a woman’s right. How can we build a society where those groups can get along without killing each other?

groups of citizens. Let’s call them the Shirts and the Skins. The Shirts believe homosexuality is an abomination that stinketh in the nostrils of the Lord, and abortion is baby murder. The Skins believe homosexuality is perfectly normal and natural, and abortion is a woman’s right. How can we build a society where those groups can get along without killing each other?

One approach might be to encourage the two sides to leave each other alone. You think homosexual sex is wrong? Fine, don’t engage in it. You think abortion is wrong? Fine, don’t have one. But don’t tell me what to do. This produces some familiar formulations. Everyone is to have the greatest amount of freedom compatible with similar freedom for everyone else. Your right to swing your arm ends where my nose begins. Live and let live.

But that answer doesn’t work for Shirts and Skins. If I really believe abortion is baby murder, it isn’t enough that I don’t do it. I also have a moral duty to prevent you from doing it. I can take a live and let live attitude about what color you paint your house. It’s none of my business. But I can’t let you murder babies. And I can’t compromise. I might accept some strategic compromise on a temporary basis, but I can never permanently accept anything short of complete abolition.

The same is true for people who really believe homosexual behavior is terribly wrong. It’s like slavery. Or cannibalism. Or human sacrifice. I can’t allow you to throw any virgins into the volcano. None. You also can’t engage in ritual cannibalism. Even on special holidays. Compromise is not an option.

The negotiation literature calls these “sacred issues.” It is insulting even to suggest compromise on a sacred issue. Sacred issues are incommensurable. If you think I might be persuaded by, say, an offer of money to compromise on a sacred issue, you simply don’t understand what a sacred issue is.

So now what? Read more »

Sughra Raza. Decay Saturated. Vermont, April, 2017.

Sughra Raza. Decay Saturated. Vermont, April, 2017. If you in any way follow AI policy, you will likely have heard that the EU AI Act’s Code of Practice (CoP) was released on July 10. This is one of the major developments in AI policy this year. 2025 has otherwise been fairly negative for AI safety and risk – the Paris AI summit in February

If you in any way follow AI policy, you will likely have heard that the EU AI Act’s Code of Practice (CoP) was released on July 10. This is one of the major developments in AI policy this year. 2025 has otherwise been fairly negative for AI safety and risk – the Paris AI summit in February

I write this not to counter Holocaust deniers. That would be a waste of time; the criminally insane will spew their fantastical vitriol no matter what you tell them. Nor do I write this in the spirit of “Never forget!” As a historian I am committed to remembering this and many more genocides, particularly the most devastating and thorough genocide of all: the European genocides of Indigenous societies. At the same time, I understand the ultimate futility of admirable slogans such as “Never Forget!” For everything is forgotten, eventually. Everything and everyone.

I write this not to counter Holocaust deniers. That would be a waste of time; the criminally insane will spew their fantastical vitriol no matter what you tell them. Nor do I write this in the spirit of “Never forget!” As a historian I am committed to remembering this and many more genocides, particularly the most devastating and thorough genocide of all: the European genocides of Indigenous societies. At the same time, I understand the ultimate futility of admirable slogans such as “Never Forget!” For everything is forgotten, eventually. Everything and everyone.

In reading about attachment theory,

In reading about attachment theory,

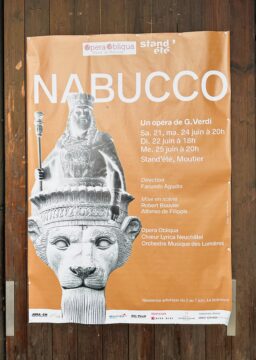

On a sunny Saturday towards the end of last month we took a train to Moutier in the west of Switzerland, half an hour from the French border, to attend an opera in a shooting range. We had tickets to hear my friend

On a sunny Saturday towards the end of last month we took a train to Moutier in the west of Switzerland, half an hour from the French border, to attend an opera in a shooting range. We had tickets to hear my friend

Americans learn about “checks and balances” from a young age. (Or at least they do to whatever extent civics is taught anymore.) We’re told that this doctrine is a corollary to the bedrock theory of “separation of powers.” Only through the former can the latter be preserved. As John Adams put it in a letter to Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, later a delegate to the First Continental Congress, in 1775: “It is by balancing each of these powers against the other two, that the efforts in human nature toward tyranny can alone be checked and restrained, and any degree of freedom preserved in the constitution.” As Trump’s efforts toward tyranny move ahead with ever-greater speed, those checks and balances feel very creaky these days.

Americans learn about “checks and balances” from a young age. (Or at least they do to whatever extent civics is taught anymore.) We’re told that this doctrine is a corollary to the bedrock theory of “separation of powers.” Only through the former can the latter be preserved. As John Adams put it in a letter to Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, later a delegate to the First Continental Congress, in 1775: “It is by balancing each of these powers against the other two, that the efforts in human nature toward tyranny can alone be checked and restrained, and any degree of freedom preserved in the constitution.” As Trump’s efforts toward tyranny move ahead with ever-greater speed, those checks and balances feel very creaky these days.